2014

This essay is expanded from the paper I presented at the ‘Hanart 100: Idiosyncrasies’ symposium in Jan. 2014. A revised version was delivered at the symposium for the exhibition ‘Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (23rd Feb. 2014).

I was born in Fujian province in 1969. This determined why, quite fortunately, I became an omnivore. I ate everything, and that enabled me to survive.

As my birthdate implies, the events that took place in the latter part of the Cultural Revolution are buried somewhere in my childhood memories. The first song I learned to sing was ‘I Love Beijing Tiananmen’. My first Chinese lesson in primary school was ‘The Grandeur of the Yangtze River Bridge at Nanjing’. From this time on, every time I received outstanding grades in a final exam, the prize certificate I was awarded always bore the image of that bridge at the top.

fig. 1 Qiu Zhijie, SNJYRB No.011# Diplomas No.2 , Installation with iron plate, chain, pulley block,4m×3.5m×2.2m,2008

Not long after I started primary school, Chairman Mao passed away, and we were bussed to the Great Hall of the People to take part in a memorial service. Everyone around me was in tears. But I didn't cry, and that made me very nervous. In a few minutes, however, I succumbed to the mournful atmosphere around me, and I too began to cry. But when everyone else stopped crying, I was still going full blast. For that alone I deserved a prize.

Although all this was taking place during the Cultural Revolution, there were still many traces of traditional Chinese culture all around us. Traditional memorial arches (pailou) still stood in the old city. My copy of the novel The Water Margin was a Republican-era edition with old-fashioned illustrations. When veteran calligraphers gathered for calligraphy and poetry events, the poems they copied were by Chairman Mao, but they used an antiquated form of script called ‘stone drum characters’ to write them. Landscape painters were sure to place a group of people holding red flags among a soaring mountain range, or insert a Yangtze River Bridge at Nanjing somewhere in their compositions, in order to make their scrolls revolutionarily correct.

When the Cultural Revolution came to an end, many venerable eccentrics emerged from the woodwork. Traditional martial arts and Chinese calligraphy were revived with a vengeance. It was at this moment that I was had my first exposure to the local literati tradition. This took place at a youth training program held at an ‘Art Hall of the Masses’, a quintessentially Socialist institution. Many of the scholarly types who taught there had survived the Cultural Revolution by writing using brush and ink to write Big Character Propaganda Posters or by designing propaganda blackboards: such was the insuppressible vitality of traditional Chinese culture. Bamboo bends in a storm, but once the storm passes, the bamboo stands erect again. One of my most inspiring teachers, Zheng Yushui, had copied the calligraphy of the famous Han-dynasty (BCE 206–220 CE) inscription, the ‘Stone Gate Eulogy’ (‘Shimen song’), on to a page from the April 1st 1965 edition of the People’s Liberation Army’s Liberation Daily newspaper (paper was expensive at the time). That page carried an article about how the Vietnamese people had shot down twelve American fighter planes the previous day, along with a quotation from Chairman Mao: ‘Imperialism is a paper tiger: strong on the outside but withered on the inside.’ At that time, Professor Zheng’s use of that particular page of the newspaper for his calligraphy practice was serious enough to constitute a crime. Twenty years later, in 1985, when I was unable to find a copy of the original rubbing of the ‘Stone Gate Eulogy’ in local bookstores, I borrowed one from Prof. Zheng, and stayed up all night copying it onto tracing paper.

I spent my youth steeped in traditional Chinese culture, an unworthy disciple of the very last generation of true Confucian scholars. When my teachers got together with monks in Buddhist temples and discussed Zen, they brought me along to grind the ink for their calligraphy practice. To do this properly, you press the inkstick down against the wetted inkstone, and rub it back and forth gently so as not to make a scratching sound. When in the proper mood, the scholars and monks would start writing, and in a short time there would be heaps of copies of classic calligraphy aphorisms, such as the ‘the music of chimes’ and ‘an affinity for brush and ink’. In a matter of minutes,they would exhaust the supply of ink that had taken me several hours to grind. I also went on outings with them when we would make rubbings from calligraphic inscriptions on cliffs and stone tablets. I was present when they recited the ancient ballad, ‘Southeast Flies the Peacock’, in an obsolete southern Fujian dialect, the sound of which brought tears to everyone’s eyes. I watched as they practiced calligraphy on red bricks with plain water for ink, as if they were doing homework exercises. During those years, I myself must have copied around 1000 Han dynasty texts. As I entered my adolescent years, I used the ancient seal script for my diary entries, fearing that others would read them. But seal script wasn’t private enough for me, so I started using even more ancient oracle-bone characters for the radicals and other elements of my diary entries. I also created my own secret alphabetic code. I’d long forgotten about this, but on a recent visit to my hometown, I came across one of those diaries. Funny, but I couldn’t make out a single word of what I had written so many years ago. This was my own version of Xu Bing's inscrutable A Book from the Sky, composed entirely of nonsense characters. Ten years after I last practiced calligraphy with water on bricks, I had my first encounter with ‘process driven art’ and the Fluxus group. My memory of brick and water calligraphy quietly morphed into my work Copying the ‘Preface to Orchid Pavilion’ One Thousand Times (1990-95).

When President Richard Nixon made his historical visit to China in 1972, I was three years old. Several years later, while I was studying painting and calligraphy, China initiated its policy of ‘open-door reform’. Thus, my boyhood diaries, written in the ancient seal script, were full of quotes by Freud, Nietzsche, Sartre, Karl Popper, Kafka, Byron and Heidegger culled from my desultory reading. My casual circle of friends was reading the Communist Manifesto, Marx’s Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and even Das Kapital. It was perhaps due to the angst brought about by my exposure to these works that in October 1986, after seeing an exhibition called ‘Xiamen Dada’, I made up my mind to pursue a career as an artist. Putting aside my dream of becoming an archeologist specializing in the study of the Dunhuang caves, I took the entrance examination for an art academy instead.

It was clear to me, even before I was admitted to an academy, that I would not study art in the conventional manner. Unlike many others at the time, I did not start out obsessed with academic training and official art, and then give it all up suddenly and become an avant-garde revolutionary. I didn't become entranced with the West, or make an effort to rediscover ancient Chinese traditions. Tales of reformed, reconciled rebels and prodigal sons returning to the nest make for happy endings, but certainly don’t apply in my case. Four different recipes, all mixed up together and inseparable, provided all the nourishment I needed in my youth: traditional scholarship, folk culture, the legacy of Socialism, and globalism.

The folk culture influence mainly comes from my native Fujian. Specifically, the southern Fujian, or Minnan, dialect preserves many elements of the ancient Chinese language and culture, and Fukienese people still practice local folk customs. For example, during the last years of the Cultural Revolution, at Chinese New Year and other traditional festivals, even Communist Party members would go home after work and worship the Daoist Supreme God of Heaven, their own ancestors and the famous Buddha in the Sanping Temple. When I was a student in the art academy, I carved a Daoist prognostication tablet out of a piece of mahogany for a relative of mine who was a Daoist fortuneteller. Thirty years of socialism in China had failed to wipe out the heterodox practices from China’s ‘southern barbarian’ territories. In that hot and humid climate, the mouldy fungus of bizarre feudal customs thrives, and the fact that many overseas Chinese trace their ancestry to Fujian confers an aura of legitimacy over these phenomena. There are temples to the goddess Mazu everywhere in Fujian; they were the first art museums I ever visited.

The above is an attempt to explain my background as an omnivore. An omnivorous diet gives animals a high level of immunity, and the ability to wear many disguises. When a particular disguise became too easy to see through, I could just as easily don another one. This is certainly the dumbest possible business strategy for an artist: At the time I was creating Copying the ‘Preface to Orchid Pavilion’ One Thousand Times, I had already become the youngest of the ‘Post-89’ generation of artists. Later I was an organizer and supporter of New Media art; a practitioner of conceptual photography; a defender of ‘Post-Sense Sensibility’ and performance art; and a vigorous proponent of Total Art and social intervention. I was like a Buddha with three heads, or a dog on a rat-catching expedition. In addition to making art, I have been a writer and a teacher, a magazine publisher and gallerist, and have even been reduced to being a curator on several occasions. Throughout all this, I never went anywhere without a Chinese brush.

My eccentricity is the product of an age of spiritual chaos, just one clinical case study in the history of a mentally ill nation. This never-ceasing, omnipresent, unfulfilled juggernaut of desire, this jumble of good and evil, violently penetrates history and the world, either turning people into stone, or incinerating them so that only their relics, like those of Jesus or the Buddha, remain.

My omnivorous background has given me a particularly strong impression: I believe that each individual is an integrated being. A person is not a cultural unit, nor are people the tools of concepts, points of view, or attitudes. People have their own accents, their own vitality, they eventually die, and take their fate with them when they depart: birth, old age, illness, death, success, failure, ups, downs. For two such fated lives to inspire each other, all that is necessary is a single, simple, soft writing brush.

I’ve studied advanced design, site management, allegorical images and techniques of sensory control. Later I learned how to make use of the power of interpretation, marketing and institutions. But these various shortcuts to success gradually came to seem dishonorable to me. Contemporary artists can produce meticulous images, but then they use mechanical reproduction and other forms of propagation to control people’s impressions. They create their own branded products and employ slaves, transforming themselves into capitalists. Some artists even take graduate courses in business management. They’re constantly seeking loopholes for registering patents on their products, even swallowing their own spit to do so. They’ll come up with a proposal for an exhibition, but keep that a secret from other artists. This all seems much too much like bare-fisted capitalism to me; it’s cowardly, undignified and shameless.

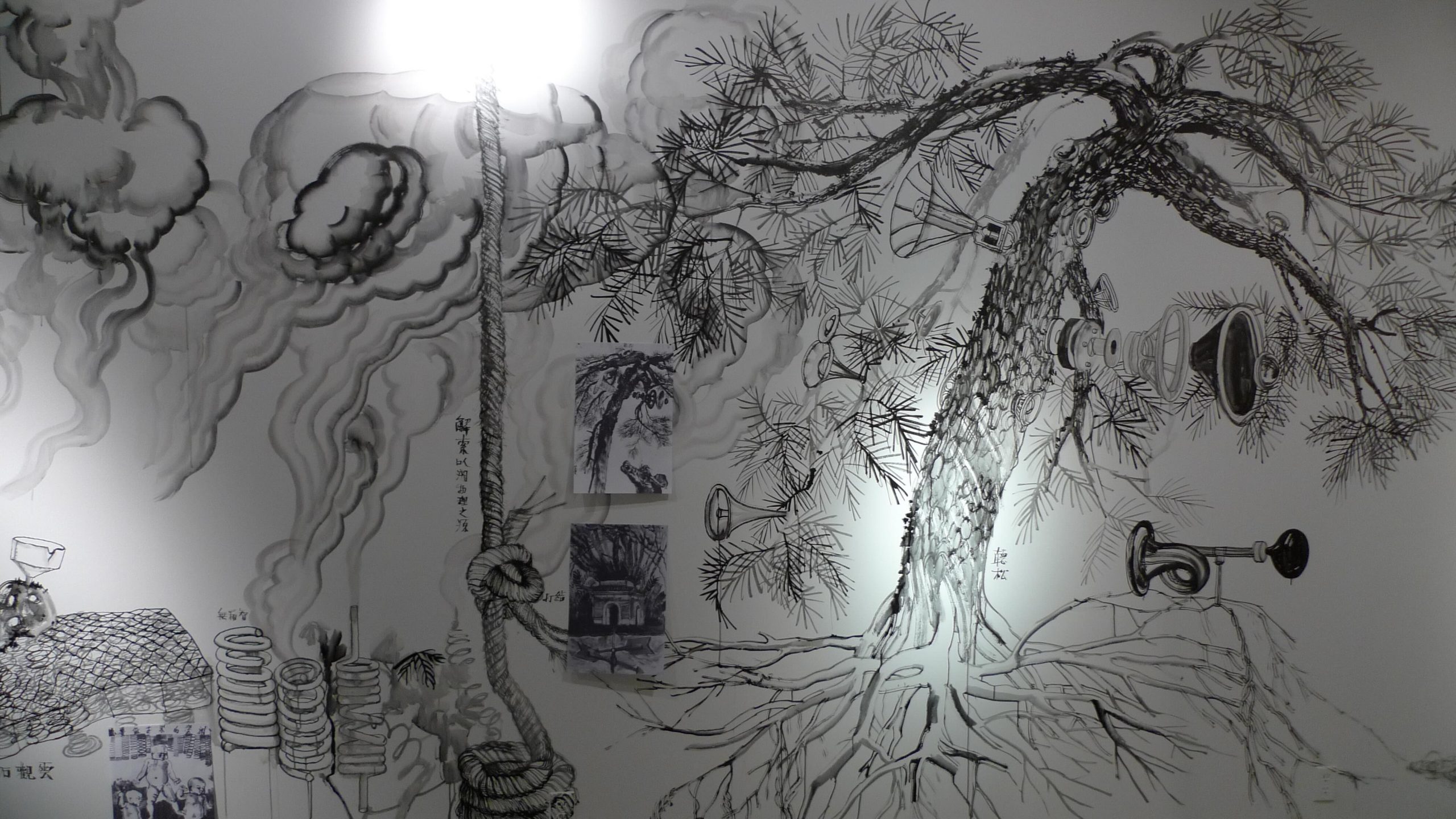

In 2009, I was in New York holding a show in a local gallery. I had arrived two days before the opening, but I found that the gallery was completely empty: The U.S. Customs had held up the delivery of my works. The gallery owner wasn't worried, and said to me, ‘You just got here, but I'm sure you'll figure something out’. So we started drinking, and continued drinking until late that night. I told the gallery owner, ‘Tomorrow, go to Chinatown, and spend $20 on a bottle of ink and two brushes.’ The next day at noon, I started painting on the walls of the gallery, and didn't stop for a full 24 hours. I painted an entire exhibition on the walls. That afternoon, I even had enough time to change my clothes for the opening. This took place at the worst point in the 2008 financial crisis, and all the contemporary galleries in Chelsea were showing small paintings. I thought that what I did was awesome, a real turn-on.

When you do Chinese ink painting and calligraphy, no assistant can possibly help you. That's cool. If a painter is well read, well travelled and has a disciplined approach to art, that will be evident in the individual character of his painting. If a painter has a powerful core of being, and is able to express that intensity in his works, that’s cool. Every stage in his life experience becomes visible, and none of his mistakes or wrong turns in life can be concealed. There is no place to hide, no way to withhold the truth. Art can be dangerous, like life itself, and like fate. That's cool. A painter shouldn't have to rely on ‘human wave attacks’, or on overly refined craftsmanship; without throwing money at expensive materials, a painter can ship an entire exhibition for very little money, and of course it's environmentally friendly; that's cool too. Because painting and calligraphy are closely related to qigong breathing exercises and the martial arts, the physical act of creation is itself a healthy form of exercise that nourishes one's qi energy. Twenty-somethings need not apply; this is the kind of art-making that only grows better as you get older. That is totally cool.

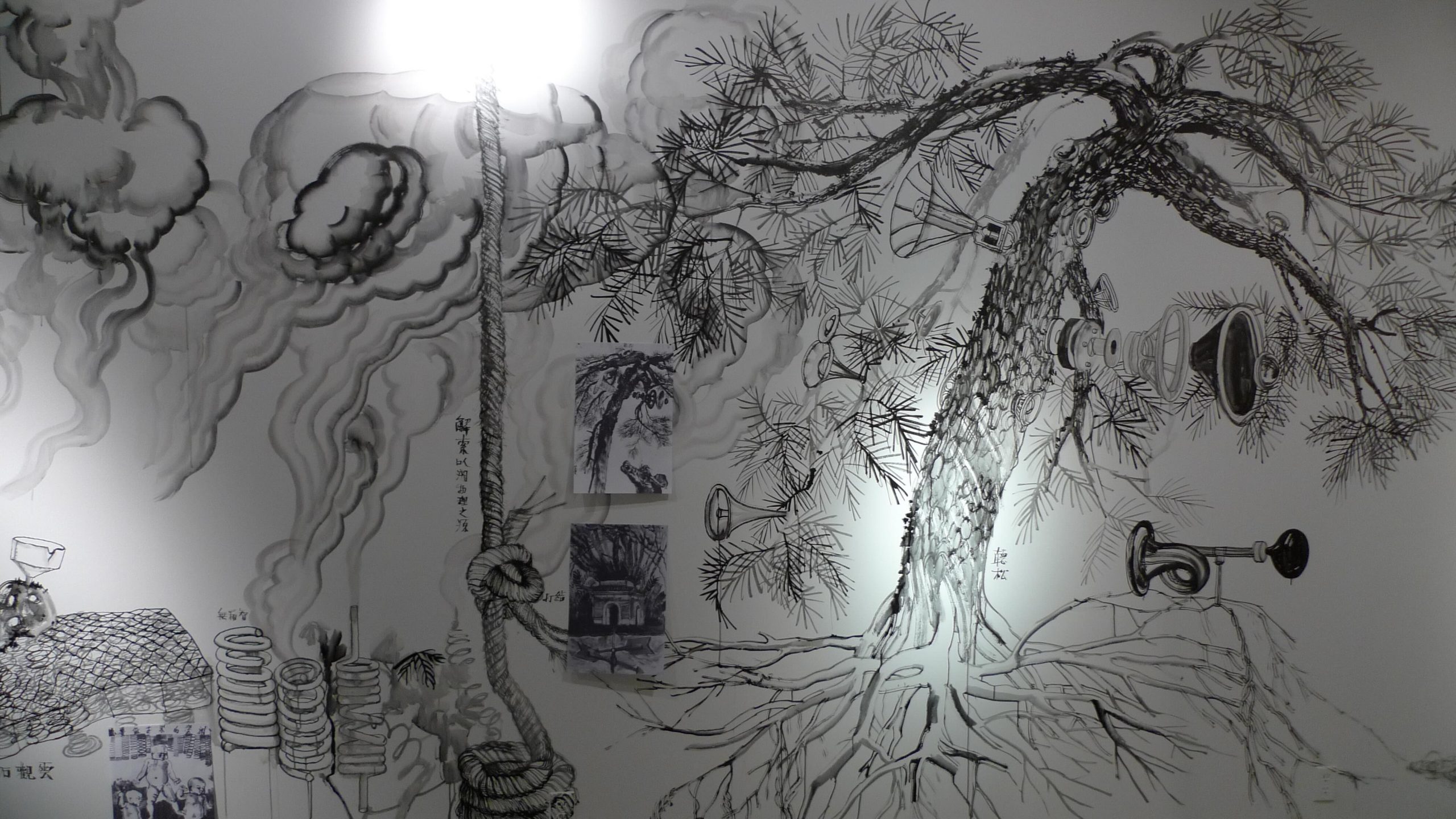

fig. 2 Qiu Zhijie, Grand View , Ink on gallery walls , Dimensions Variable ,2011

For the above reasons, I increasingly enjoy painting on walls and wiping the work away after the exhibition. That drives collectors crazy, but it's a special treat for other viewers, who can get up close and have a more intimate relationship with the work. It's a little like making love—candid, involved, sincere, committed and, above all, dignified.

Practicing calligraphy and painting are not forms of escape. They’re different from sitting in a lotus position with classical Chinese music in the background, faking nirvana, or pretending that you have extinguished all evil thoughts from your mind. It's not like dressing up like a scholar and giving Tai Chi lessons to foreigners. On the contrary, I have never cut myself off from deep involvement in Chinese society; in fact, in the past few years I have only become more active.

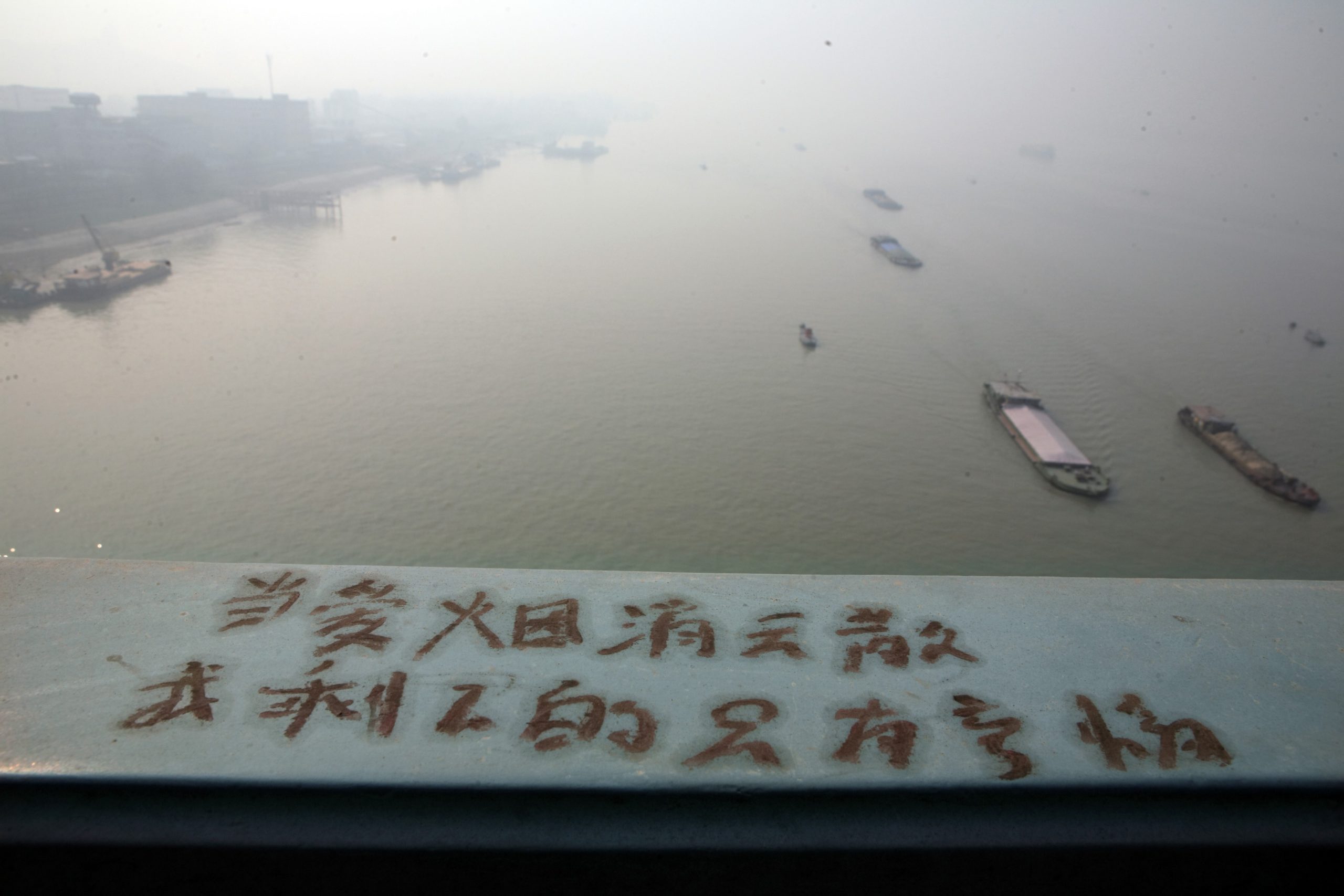

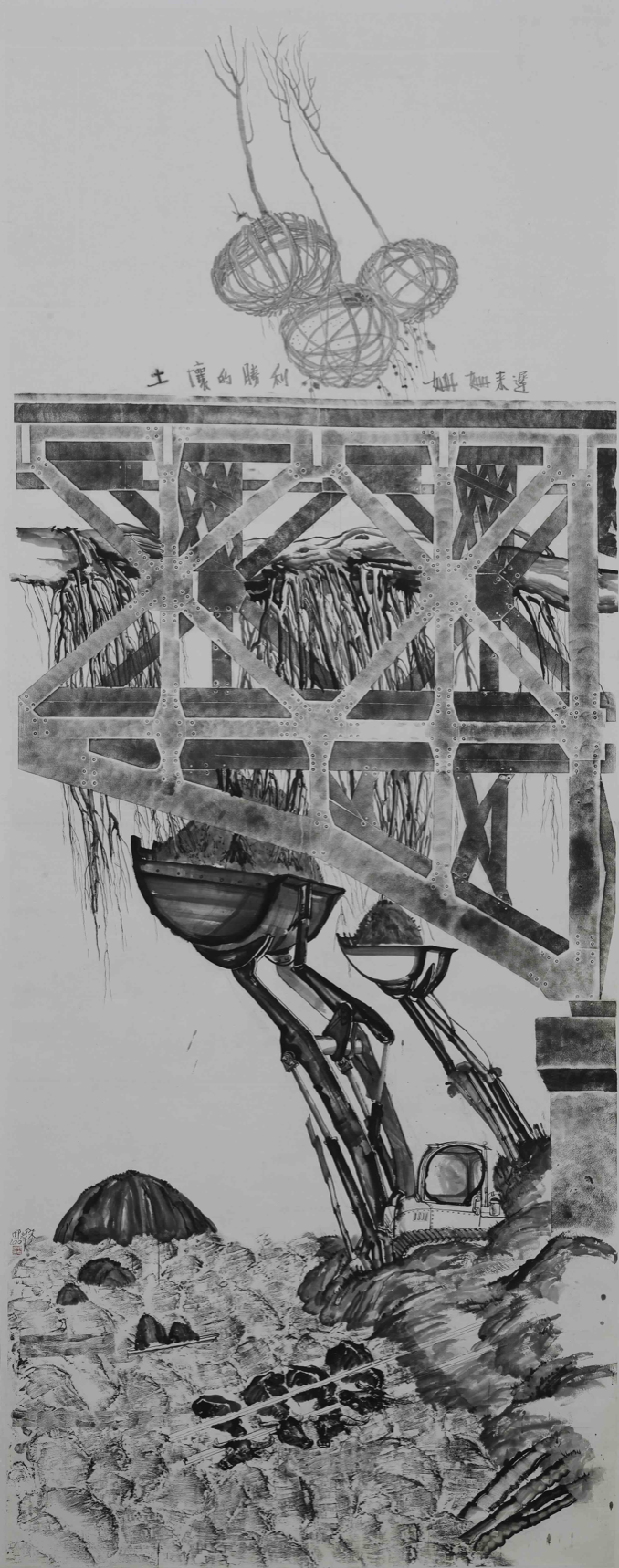

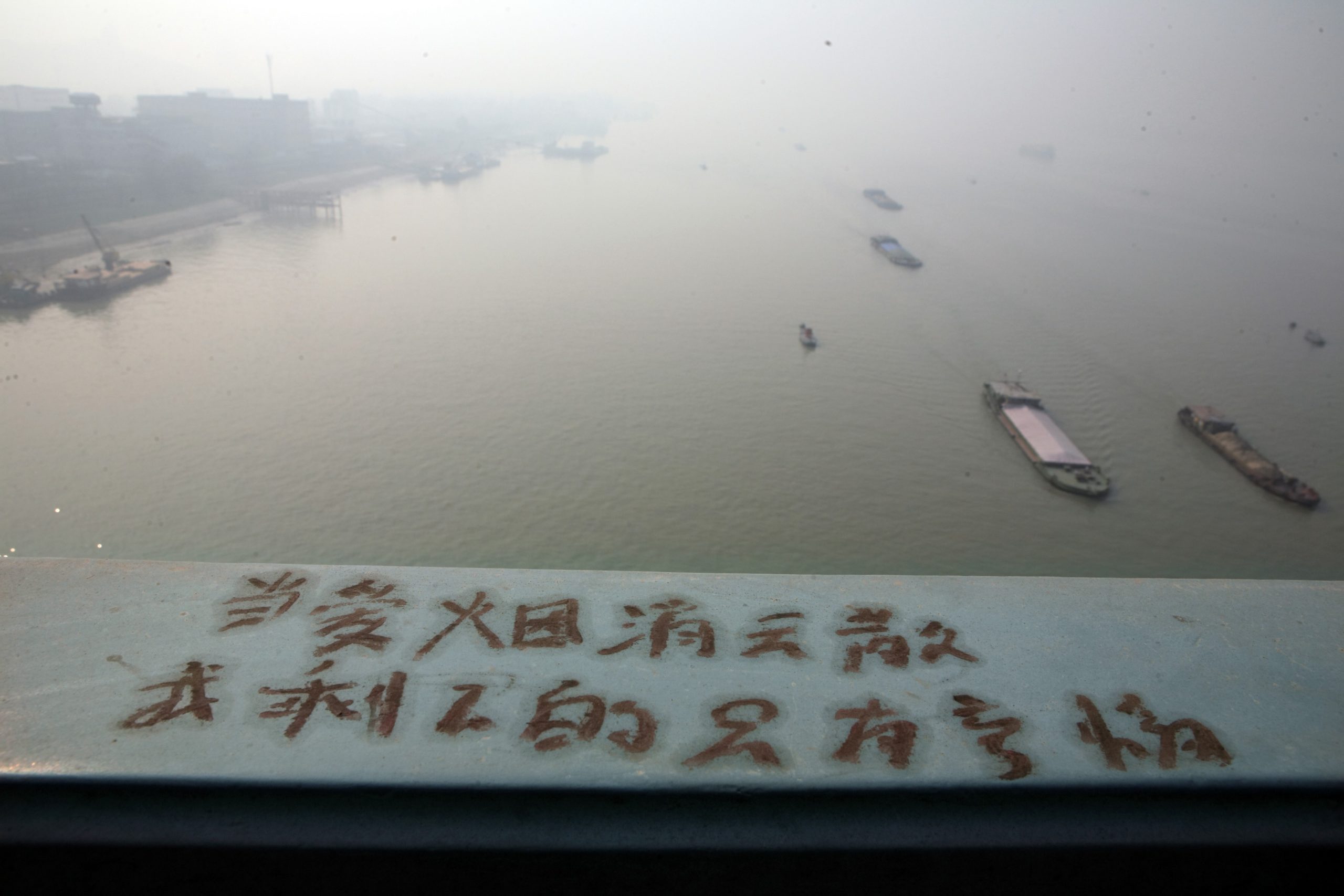

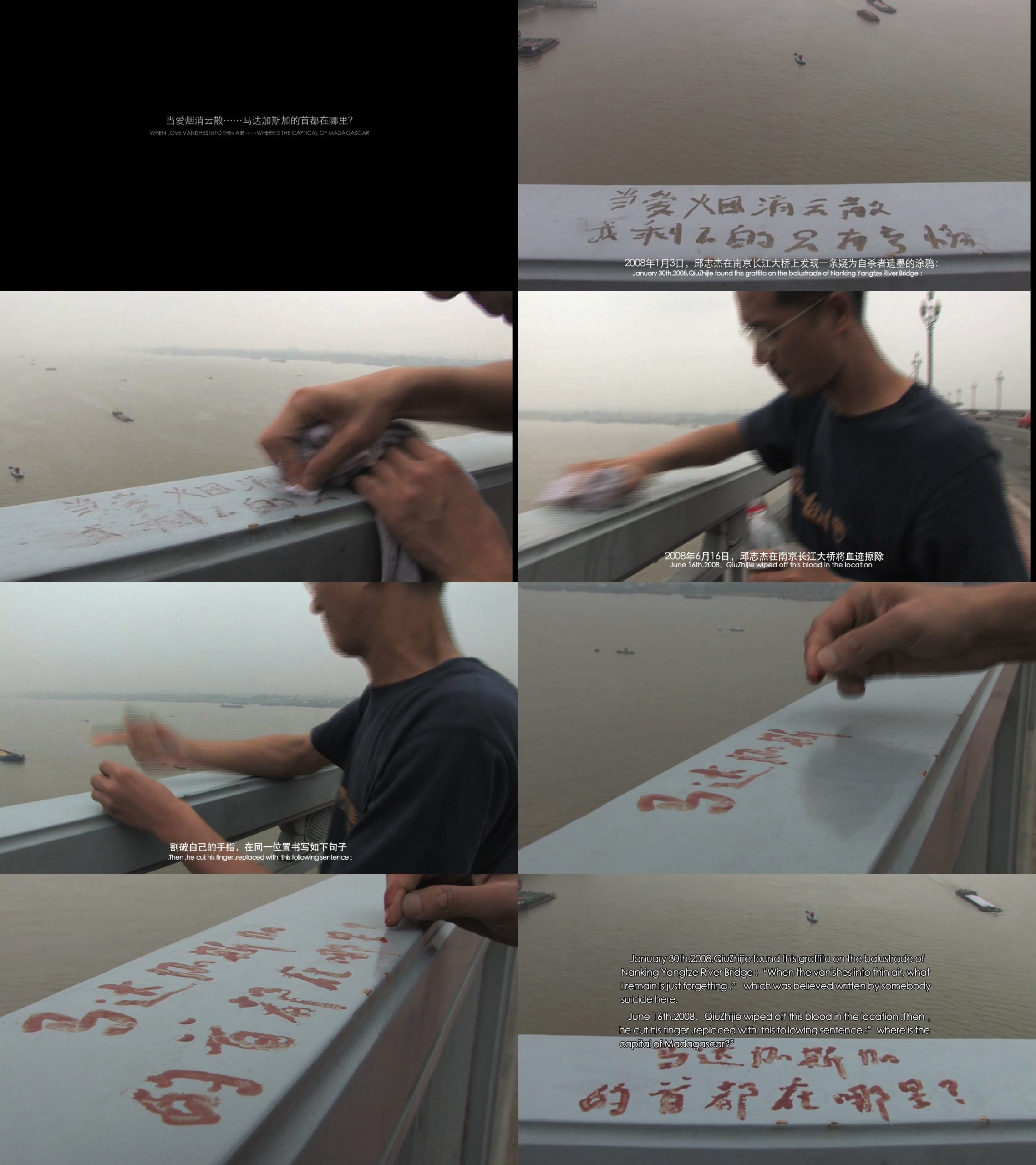

In January 2008, I removed suicide note written in blood on a guardrail on the Yangtze River Bridge in Nanjing. It read, ‘When my love left me like vanishing smoke and clouds, all that remained was my despair’. At the time, I was taking part in a project to discourage suicides on the Yangtze River Bridge.

fig. 3 Suicide note written in blood on the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge, reading: ‘When my love left me like vanishing smoke and clouds, all that remained was my despair.’ Photograph by Qiu Zhijie ,2008

Built in 1968, the bridge has been around as long as I have. The picture of the bridge that was printed on all my primary school prize certificates served as a memorial to the revolution, to China’s national independence and to modernity; it was also a symbol of progress. But forty years later, when I brought my own calligraphy on the bridge, it was already an ideological anachronism. According to Chinese government records, in the past forty years, more than 2000 people have lost their lives jumping off the Yangtze River Bridge. By comparison, 1200 people have killed themselves on the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco since it opened in 1937. In 2007, I began to carry out social surveys, collaborating with students and other non-governmental volunteers on a project to prevent suicides on the bridge. Suicide prevention, acting as a sounding board for other people’s severe depression, is a risky enterprise, requiring a strong and independent soul. In this respect, painting and calligraphy served as a talisman to ward off evil influences.

In 2008, I met some individual cases on the bridge, losers in the game of modern history, people with no way out. One by one, I tried to dissuade them from ending their lives. There are images and words from that time and place that play over and over again in my mind, growing more distinct with each reappearance. These pictures and voices have settled in my brain, and refuse to go away. When I stand on the bridge, I often recall what I felt just before my daughter was born. Someday I will share these unforgettable images and phrases with her. The only way for me to do this is through painting and calligraphy.

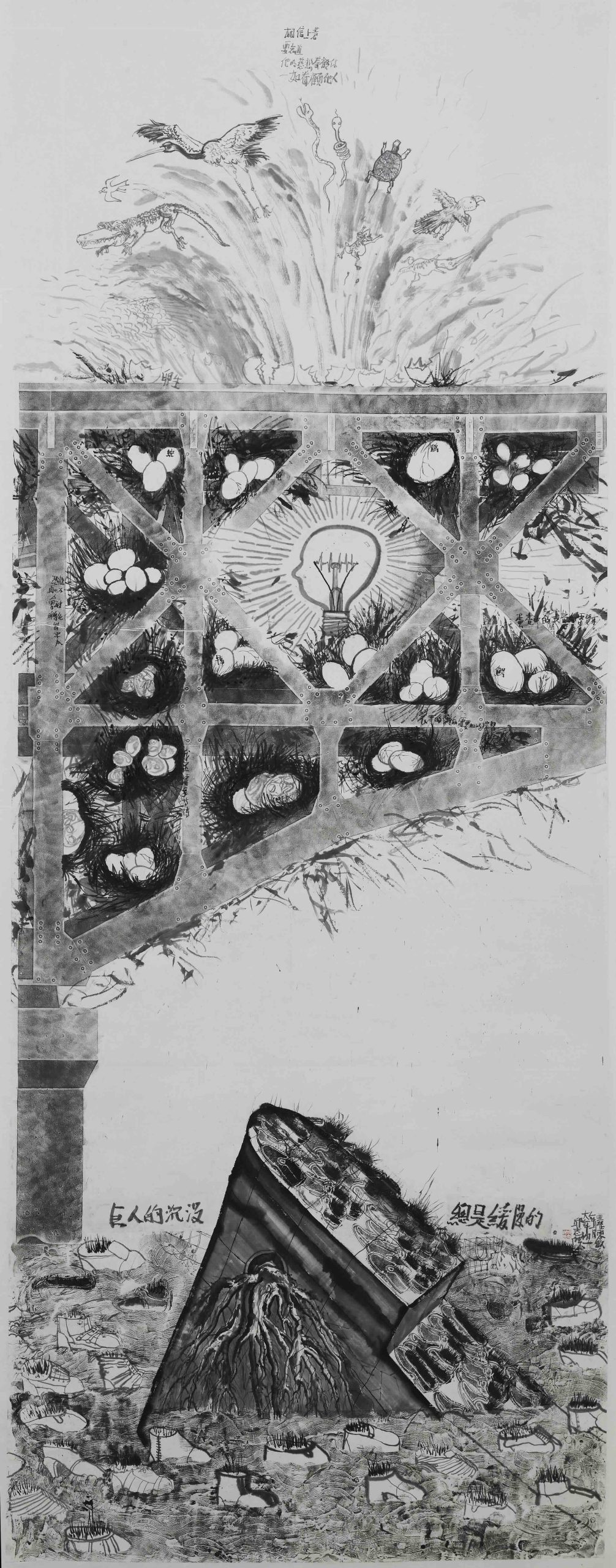

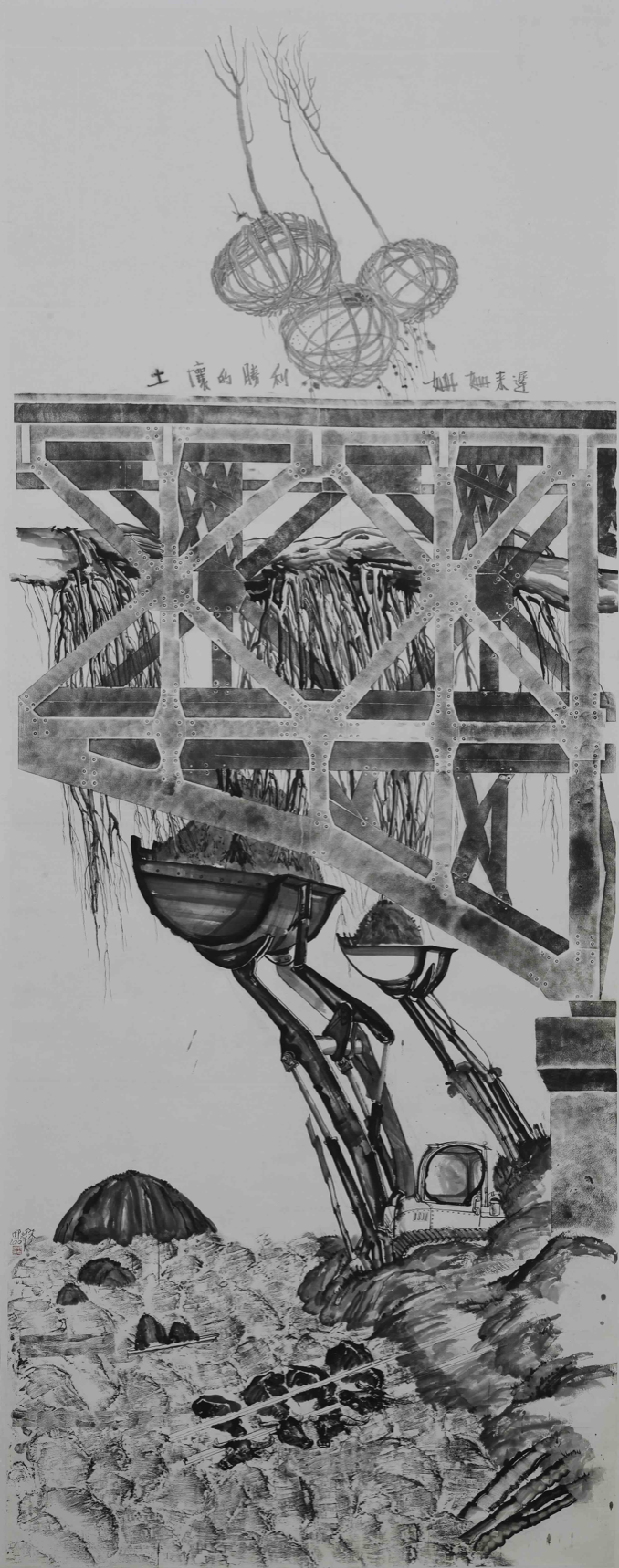

Chinese brush painting is the art of the loser, of the failure. It is the art of the damned. At the same time, the reason why many people choose to die on the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge is because the age we live is devoid of the true spirit of painting and calligraphy. A Chinese brush is a tool for writing letters; it is the kiss a father should give his daughter when he wants to share his thoughts with her. My installation for the Metropolitan Museum 's exhibition was called Thirty Letters to Qiu Jiawa . The thirty paintings included images of the nine girders of the Yangtze River Bridge. There are fathers and sons who end their lives, and a father and a daughter who go through life together.

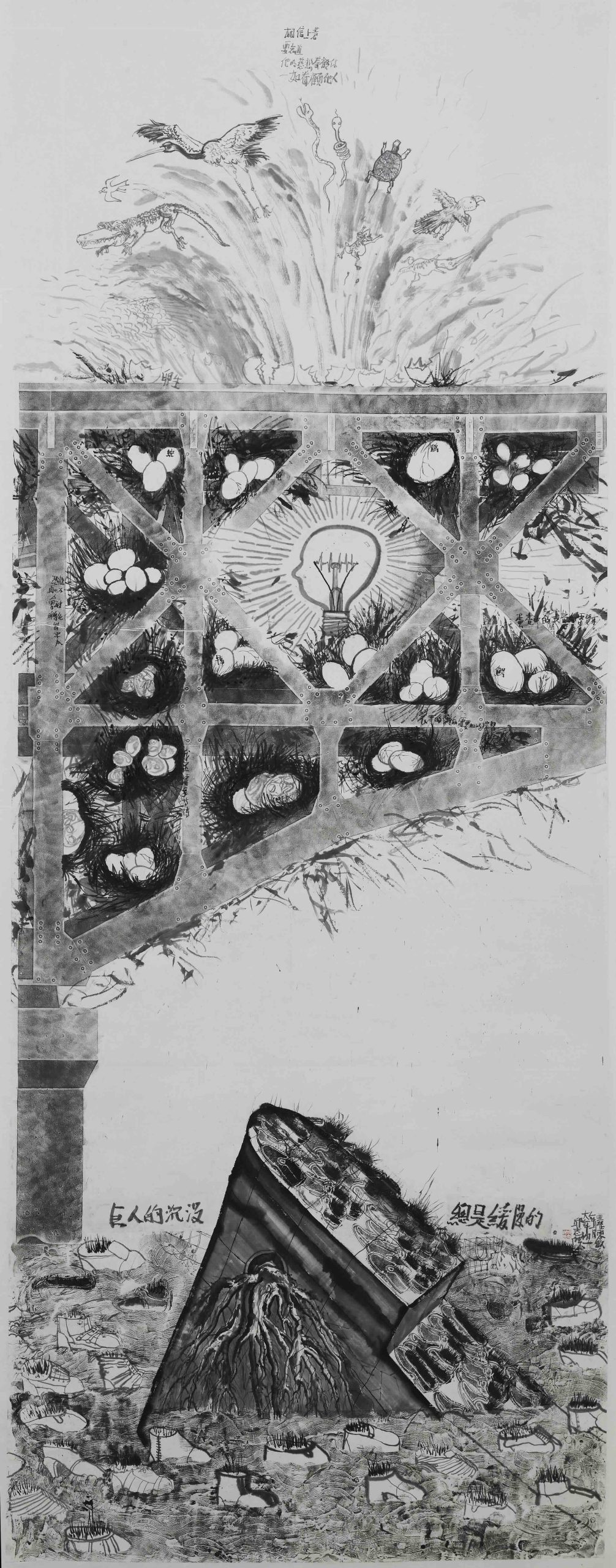

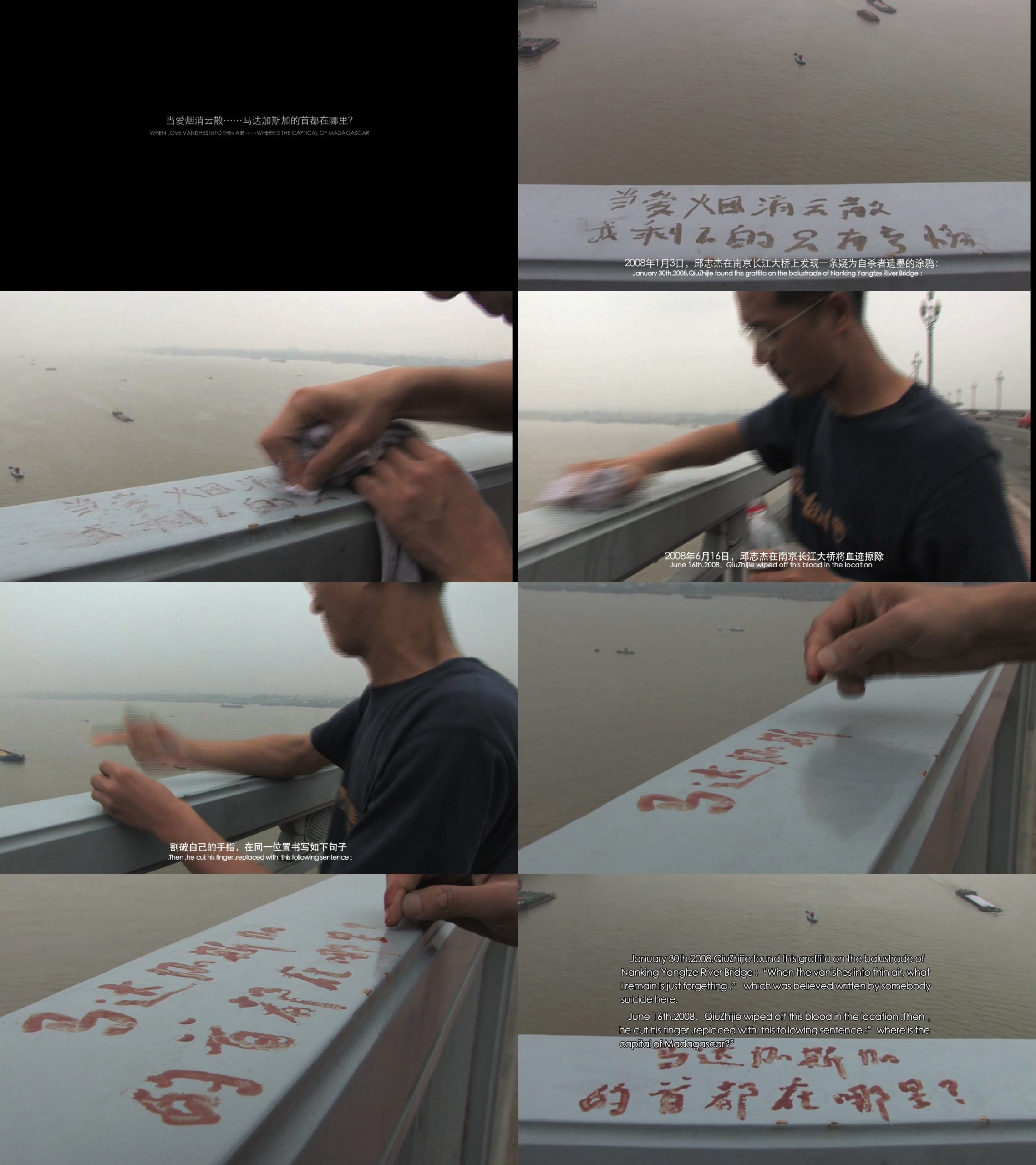

fig. 4a Qiu Zhijie, 30 Letters to Qiu Jiawa: The sinking of a giant is always slow, Ink on Paper, 90×500cm,2009

fig. 4b Qiu Zhijie, 30 Letters to Qiu Jiawa: Nobody can prohibit you from stealing pleasure, Ink on Paper, 190×500cm,2009

fig. 4c Qiu Zhijie, 30 Letters to Qiu Jiawa: Belated is the victory of the soil, Ink on Paper,144×300cm, 2009

Many tourists take photographs on the Yangtze River Bridge, and have the photos printed on a cup as a souvenir of their visit. I've taken rubbings from the graffiti on the bridge, and had them printed on the back side of a cup. This is my own ‘I was here memorial tablet'.

On the billboards alongside the bridge, there's an advertisement for luxury residences. The text reads: ‘The world allows those with foresight to get ahead'. Over the past forty years, the keyword in Chinese society has gone from ‘revolution’ to ‘success’, but the standards for attaining that success have become more and more narrowly defined. This is the ideology that has forced those who cannot ‘succeed’ to jump off the bridge. When I drove from Beijing to Nanjing, and crossed over the Yangtze River Bridge, I left behind a lengthy trail of messages that I had carved into the tires of my car, like a rubber stamp: This was the ‘Way of Failure’.

In the summer of 2008, I scratched off a suicide note written on the bridge in blood, and cut my own finger. I wrote, in my own blood, ‘Where is the capital of Madagascar?’. My calligraphy was poor. I was in pain, and my hand was shaking.

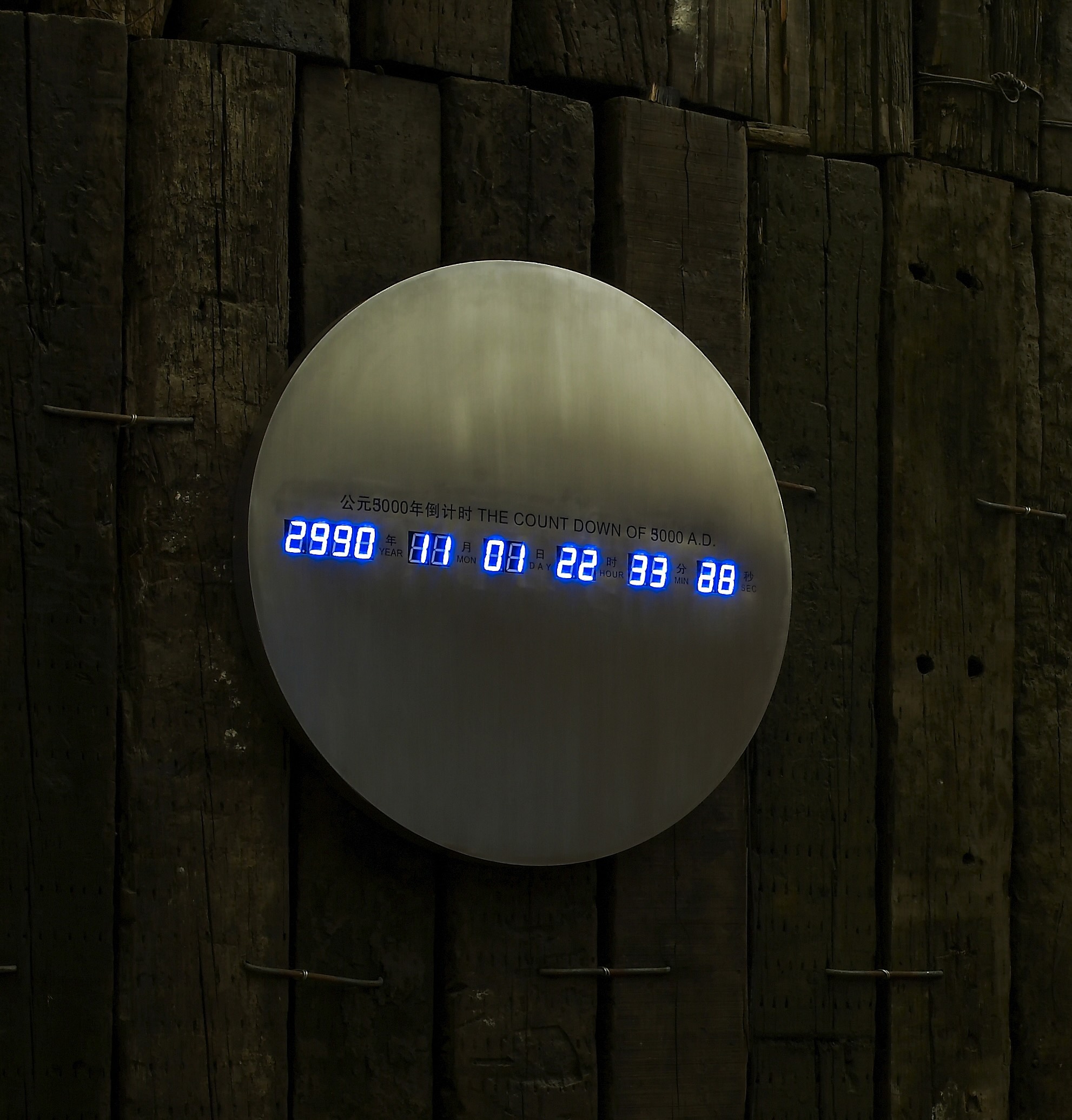

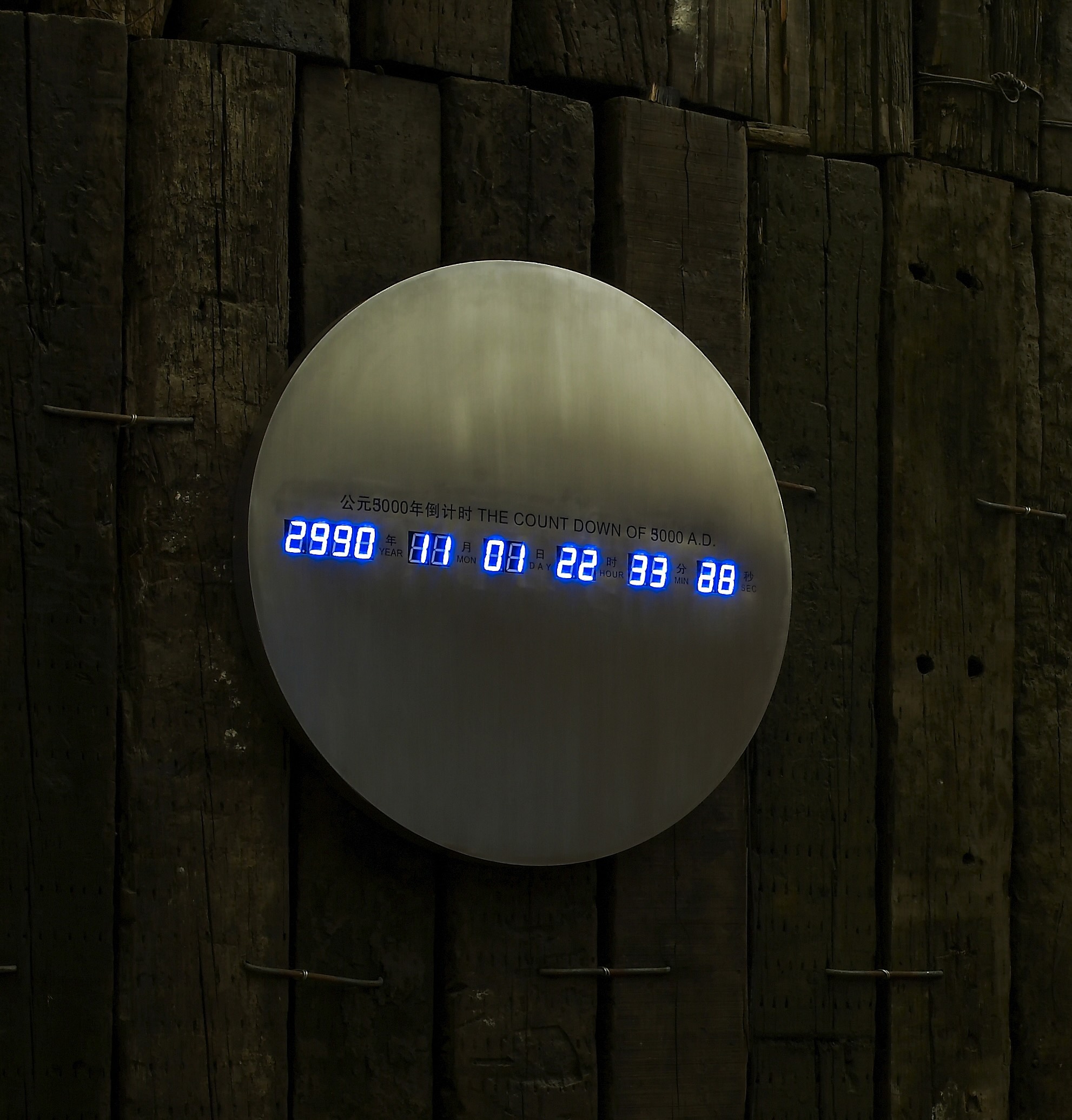

People ask me why I wrote that line. In fact, many people have wondered about that. I show them the picture of my work, The Countdown of 5000 A.D. When we are on the bridge, steaming in the sauna of failure, with no way out, we need something that is more remote than fate to provide comfort for our souls. The very opposite of The Countdown of 5000 A.D. is the countdown clock that was erected in Tiananmen Square for the 2008 Beijing Olympics, an absurd joke if there ever was one: a purely political joke.

fig. 5 Qiu Zhijie, SNJYRB No.106# : Love is dead...where is the capital of Madagascar? , Performance, photo-installation and video, 2008

fig. 6 Qiu Zhijie, The Countdown of 5000 A.D. , Installation, stainless steel with electronic components, 2009

So, the kind of work I do has come full circle. On the surface, it appears that saving people's lives on the bridge, teaching, and curating art exhibitions are all respectable forms of social engagement. Painting and calligraphy, on the other hand, are extremely private and personal practices; the closest one can come to self-cultivation. Chance and fate play a role in all my acts of social engagement. As I see, this is the same as the path of the traditional Confucian scholar: In poverty, do the best you can to preserve yourself; if you succeed, then spread your good fortune to others.

In fact, even the most superficial form of social involvement presents an opportunity to practice self-cultivation. The more time I spent on the bridge, the more idiosyncratic and dense my brushwork and imagery became, rather than falling repeatedly into traditional patterns. As my commitment to calligraphy and painting deepens, my soul grows more responsive and I acquire greater freedom.

Only when I am actually touching brush to paper, as if there were no turning back, does my calligraphy and painting give me inner strength, and the courage to visit the bridge repeatedly; these visits are in themselves a form of intervention. That may explain why, in my painting, I do not depict gnarled trees, forests in winter, pine trees, bubbling springs and elegant scholars in long robes. We eat meat, we don't practice meditation, and we worry constantly, and thus we are destined to go to hell. But because I have been omnivorous since I was a boy, in this regard I have nothing to fear.

Recently, I have been working on an art therapy programme for a group dedicated to preventing suicides on the Yangtze River Bridge. My daughter, Qiu Jiawa, is five years old, and it's time for her to start learning calligraphy. I've copied out the Taishan Diamond Sutra, and told her to trace the characters in her own hand over mine. I believe that calligraphy and painting, Tang and Song poetry, and Chinese characters will provide her with a good luck charm, a talisman that will enable her to survive any form of inferno.

In time, when our generation has passed on, Qiu Jiawa will copy out a text for her children, and tell them to trace the characters in their own hand.

Chinese people don’t believe in immortality. But the energy that is inside them, that is authentically theirs, never dies; it passes on down, from one generation to the next.

This essay is expanded from the paper I presented at the ‘Hanart 100: Idiosyncrasies’ symposium in Jan. 2014. A revised version was delivered at the symposium for the exhibition ‘Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (23rd Feb. 2014).

I was born in Fujian province in 1969. This determined why, quite fortunately, I became an omnivore. I ate everything, and that enabled me to survive.

As my birthdate implies, the events that took place in the latter part of the Cultural Revolution are buried somewhere in my childhood memories. The first song I learned to sing was ‘I Love Beijing Tiananmen’. My first Chinese lesson in primary school was ‘The Grandeur of the Yangtze River Bridge at Nanjing’. From this time on, every time I received outstanding grades in a final exam, the prize certificate I was awarded always bore the image of that bridge at the top.

fig. 1 Qiu Zhijie, SNJYRB No.011# Diplomas No.2 , Installation with iron plate, chain, pulley block,4m×3.5m×2.2m,2008

Not long after I started primary school, Chairman Mao passed away, and we were bussed to the Great Hall of the People to take part in a memorial service. Everyone around me was in tears. But I didn't cry, and that made me very nervous. In a few minutes, however, I succumbed to the mournful atmosphere around me, and I too began to cry. But when everyone else stopped crying, I was still going full blast. For that alone I deserved a prize.

Although all this was taking place during the Cultural Revolution, there were still many traces of traditional Chinese culture all around us. Traditional memorial arches (pailou) still stood in the old city. My copy of the novel The Water Margin was a Republican-era edition with old-fashioned illustrations. When veteran calligraphers gathered for calligraphy and poetry events, the poems they copied were by Chairman Mao, but they used an antiquated form of script called ‘stone drum characters’ to write them. Landscape painters were sure to place a group of people holding red flags among a soaring mountain range, or insert a Yangtze River Bridge at Nanjing somewhere in their compositions, in order to make their scrolls revolutionarily correct.

When the Cultural Revolution came to an end, many venerable eccentrics emerged from the woodwork. Traditional martial arts and Chinese calligraphy were revived with a vengeance. It was at this moment that I was had my first exposure to the local literati tradition. This took place at a youth training program held at an ‘Art Hall of the Masses’, a quintessentially Socialist institution. Many of the scholarly types who taught there had survived the Cultural Revolution by writing using brush and ink to write Big Character Propaganda Posters or by designing propaganda blackboards: such was the insuppressible vitality of traditional Chinese culture. Bamboo bends in a storm, but once the storm passes, the bamboo stands erect again. One of my most inspiring teachers, Zheng Yushui, had copied the calligraphy of the famous Han-dynasty (BCE 206–220 CE) inscription, the ‘Stone Gate Eulogy’ (‘Shimen song’), on to a page from the April 1st 1965 edition of the People’s Liberation Army’s Liberation Daily newspaper (paper was expensive at the time). That page carried an article about how the Vietnamese people had shot down twelve American fighter planes the previous day, along with a quotation from Chairman Mao: ‘Imperialism is a paper tiger: strong on the outside but withered on the inside.’ At that time, Professor Zheng’s use of that particular page of the newspaper for his calligraphy practice was serious enough to constitute a crime. Twenty years later, in 1985, when I was unable to find a copy of the original rubbing of the ‘Stone Gate Eulogy’ in local bookstores, I borrowed one from Prof. Zheng, and stayed up all night copying it onto tracing paper.

I spent my youth steeped in traditional Chinese culture, an unworthy disciple of the very last generation of true Confucian scholars. When my teachers got together with monks in Buddhist temples and discussed Zen, they brought me along to grind the ink for their calligraphy practice. To do this properly, you press the inkstick down against the wetted inkstone, and rub it back and forth gently so as not to make a scratching sound. When in the proper mood, the scholars and monks would start writing, and in a short time there would be heaps of copies of classic calligraphy aphorisms, such as the ‘the music of chimes’ and ‘an affinity for brush and ink’. In a matter of minutes,they would exhaust the supply of ink that had taken me several hours to grind. I also went on outings with them when we would make rubbings from calligraphic inscriptions on cliffs and stone tablets. I was present when they recited the ancient ballad, ‘Southeast Flies the Peacock’, in an obsolete southern Fujian dialect, the sound of which brought tears to everyone’s eyes. I watched as they practiced calligraphy on red bricks with plain water for ink, as if they were doing homework exercises. During those years, I myself must have copied around 1000 Han dynasty texts. As I entered my adolescent years, I used the ancient seal script for my diary entries, fearing that others would read them. But seal script wasn’t private enough for me, so I started using even more ancient oracle-bone characters for the radicals and other elements of my diary entries. I also created my own secret alphabetic code. I’d long forgotten about this, but on a recent visit to my hometown, I came across one of those diaries. Funny, but I couldn’t make out a single word of what I had written so many years ago. This was my own version of Xu Bing's inscrutable A Book from the Sky, composed entirely of nonsense characters. Ten years after I last practiced calligraphy with water on bricks, I had my first encounter with ‘process driven art’ and the Fluxus group. My memory of brick and water calligraphy quietly morphed into my work Copying the ‘Preface to Orchid Pavilion’ One Thousand Times (1990-95).

When President Richard Nixon made his historical visit to China in 1972, I was three years old. Several years later, while I was studying painting and calligraphy, China initiated its policy of ‘open-door reform’. Thus, my boyhood diaries, written in the ancient seal script, were full of quotes by Freud, Nietzsche, Sartre, Karl Popper, Kafka, Byron and Heidegger culled from my desultory reading. My casual circle of friends was reading the Communist Manifesto, Marx’s Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and even Das Kapital. It was perhaps due to the angst brought about by my exposure to these works that in October 1986, after seeing an exhibition called ‘Xiamen Dada’, I made up my mind to pursue a career as an artist. Putting aside my dream of becoming an archeologist specializing in the study of the Dunhuang caves, I took the entrance examination for an art academy instead.

It was clear to me, even before I was admitted to an academy, that I would not study art in the conventional manner. Unlike many others at the time, I did not start out obsessed with academic training and official art, and then give it all up suddenly and become an avant-garde revolutionary. I didn't become entranced with the West, or make an effort to rediscover ancient Chinese traditions. Tales of reformed, reconciled rebels and prodigal sons returning to the nest make for happy endings, but certainly don’t apply in my case. Four different recipes, all mixed up together and inseparable, provided all the nourishment I needed in my youth: traditional scholarship, folk culture, the legacy of Socialism, and globalism.

The folk culture influence mainly comes from my native Fujian. Specifically, the southern Fujian, or Minnan, dialect preserves many elements of the ancient Chinese language and culture, and Fukienese people still practice local folk customs. For example, during the last years of the Cultural Revolution, at Chinese New Year and other traditional festivals, even Communist Party members would go home after work and worship the Daoist Supreme God of Heaven, their own ancestors and the famous Buddha in the Sanping Temple. When I was a student in the art academy, I carved a Daoist prognostication tablet out of a piece of mahogany for a relative of mine who was a Daoist fortuneteller. Thirty years of socialism in China had failed to wipe out the heterodox practices from China’s ‘southern barbarian’ territories. In that hot and humid climate, the mouldy fungus of bizarre feudal customs thrives, and the fact that many overseas Chinese trace their ancestry to Fujian confers an aura of legitimacy over these phenomena. There are temples to the goddess Mazu everywhere in Fujian; they were the first art museums I ever visited.

The above is an attempt to explain my background as an omnivore. An omnivorous diet gives animals a high level of immunity, and the ability to wear many disguises. When a particular disguise became too easy to see through, I could just as easily don another one. This is certainly the dumbest possible business strategy for an artist: At the time I was creating Copying the ‘Preface to Orchid Pavilion’ One Thousand Times, I had already become the youngest of the ‘Post-89’ generation of artists. Later I was an organizer and supporter of New Media art; a practitioner of conceptual photography; a defender of ‘Post-Sense Sensibility’ and performance art; and a vigorous proponent of Total Art and social intervention. I was like a Buddha with three heads, or a dog on a rat-catching expedition. In addition to making art, I have been a writer and a teacher, a magazine publisher and gallerist, and have even been reduced to being a curator on several occasions. Throughout all this, I never went anywhere without a Chinese brush.

My eccentricity is the product of an age of spiritual chaos, just one clinical case study in the history of a mentally ill nation. This never-ceasing, omnipresent, unfulfilled juggernaut of desire, this jumble of good and evil, violently penetrates history and the world, either turning people into stone, or incinerating them so that only their relics, like those of Jesus or the Buddha, remain.

My omnivorous background has given me a particularly strong impression: I believe that each individual is an integrated being. A person is not a cultural unit, nor are people the tools of concepts, points of view, or attitudes. People have their own accents, their own vitality, they eventually die, and take their fate with them when they depart: birth, old age, illness, death, success, failure, ups, downs. For two such fated lives to inspire each other, all that is necessary is a single, simple, soft writing brush.

I’ve studied advanced design, site management, allegorical images and techniques of sensory control. Later I learned how to make use of the power of interpretation, marketing and institutions. But these various shortcuts to success gradually came to seem dishonorable to me. Contemporary artists can produce meticulous images, but then they use mechanical reproduction and other forms of propagation to control people’s impressions. They create their own branded products and employ slaves, transforming themselves into capitalists. Some artists even take graduate courses in business management. They’re constantly seeking loopholes for registering patents on their products, even swallowing their own spit to do so. They’ll come up with a proposal for an exhibition, but keep that a secret from other artists. This all seems much too much like bare-fisted capitalism to me; it’s cowardly, undignified and shameless.

In 2009, I was in New York holding a show in a local gallery. I had arrived two days before the opening, but I found that the gallery was completely empty: The U.S. Customs had held up the delivery of my works. The gallery owner wasn't worried, and said to me, ‘You just got here, but I'm sure you'll figure something out’. So we started drinking, and continued drinking until late that night. I told the gallery owner, ‘Tomorrow, go to Chinatown, and spend $20 on a bottle of ink and two brushes.’ The next day at noon, I started painting on the walls of the gallery, and didn't stop for a full 24 hours. I painted an entire exhibition on the walls. That afternoon, I even had enough time to change my clothes for the opening. This took place at the worst point in the 2008 financial crisis, and all the contemporary galleries in Chelsea were showing small paintings. I thought that what I did was awesome, a real turn-on.

When you do Chinese ink painting and calligraphy, no assistant can possibly help you. That's cool. If a painter is well read, well travelled and has a disciplined approach to art, that will be evident in the individual character of his painting. If a painter has a powerful core of being, and is able to express that intensity in his works, that’s cool. Every stage in his life experience becomes visible, and none of his mistakes or wrong turns in life can be concealed. There is no place to hide, no way to withhold the truth. Art can be dangerous, like life itself, and like fate. That's cool. A painter shouldn't have to rely on ‘human wave attacks’, or on overly refined craftsmanship; without throwing money at expensive materials, a painter can ship an entire exhibition for very little money, and of course it's environmentally friendly; that's cool too. Because painting and calligraphy are closely related to qigong breathing exercises and the martial arts, the physical act of creation is itself a healthy form of exercise that nourishes one's qi energy. Twenty-somethings need not apply; this is the kind of art-making that only grows better as you get older. That is totally cool.

fig. 2 Qiu Zhijie, Grand View , Ink on gallery walls , Dimensions Variable ,2011

For the above reasons, I increasingly enjoy painting on walls and wiping the work away after the exhibition. That drives collectors crazy, but it's a special treat for other viewers, who can get up close and have a more intimate relationship with the work. It's a little like making love—candid, involved, sincere, committed and, above all, dignified.

Practicing calligraphy and painting are not forms of escape. They’re different from sitting in a lotus position with classical Chinese music in the background, faking nirvana, or pretending that you have extinguished all evil thoughts from your mind. It's not like dressing up like a scholar and giving Tai Chi lessons to foreigners. On the contrary, I have never cut myself off from deep involvement in Chinese society; in fact, in the past few years I have only become more active.

In January 2008, I removed suicide note written in blood on a guardrail on the Yangtze River Bridge in Nanjing. It read, ‘When my love left me like vanishing smoke and clouds, all that remained was my despair’. At the time, I was taking part in a project to discourage suicides on the Yangtze River Bridge.

fig. 3 Suicide note written in blood on the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge, reading: ‘When my love left me like vanishing smoke and clouds, all that remained was my despair.’ Photograph by Qiu Zhijie ,2008

Built in 1968, the bridge has been around as long as I have. The picture of the bridge that was printed on all my primary school prize certificates served as a memorial to the revolution, to China’s national independence and to modernity; it was also a symbol of progress. But forty years later, when I brought my own calligraphy on the bridge, it was already an ideological anachronism. According to Chinese government records, in the past forty years, more than 2000 people have lost their lives jumping off the Yangtze River Bridge. By comparison, 1200 people have killed themselves on the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco since it opened in 1937. In 2007, I began to carry out social surveys, collaborating with students and other non-governmental volunteers on a project to prevent suicides on the bridge. Suicide prevention, acting as a sounding board for other people’s severe depression, is a risky enterprise, requiring a strong and independent soul. In this respect, painting and calligraphy served as a talisman to ward off evil influences.

In 2008, I met some individual cases on the bridge, losers in the game of modern history, people with no way out. One by one, I tried to dissuade them from ending their lives. There are images and words from that time and place that play over and over again in my mind, growing more distinct with each reappearance. These pictures and voices have settled in my brain, and refuse to go away. When I stand on the bridge, I often recall what I felt just before my daughter was born. Someday I will share these unforgettable images and phrases with her. The only way for me to do this is through painting and calligraphy.

Chinese brush painting is the art of the loser, of the failure. It is the art of the damned. At the same time, the reason why many people choose to die on the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge is because the age we live is devoid of the true spirit of painting and calligraphy. A Chinese brush is a tool for writing letters; it is the kiss a father should give his daughter when he wants to share his thoughts with her. My installation for the Metropolitan Museum 's exhibition was called Thirty Letters to Qiu Jiawa . The thirty paintings included images of the nine girders of the Yangtze River Bridge. There are fathers and sons who end their lives, and a father and a daughter who go through life together.

fig. 4a Qiu Zhijie, 30 Letters to Qiu Jiawa: The sinking of a giant is always slow, Ink on Paper, 90×500cm,2009

fig. 4b Qiu Zhijie, 30 Letters to Qiu Jiawa: Nobody can prohibit you from stealing pleasure, Ink on Paper, 190×500cm,2009

fig. 4c Qiu Zhijie, 30 Letters to Qiu Jiawa: Belated is the victory of the soil, Ink on Paper,144×300cm, 2009

Many tourists take photographs on the Yangtze River Bridge, and have the photos printed on a cup as a souvenir of their visit. I've taken rubbings from the graffiti on the bridge, and had them printed on the back side of a cup. This is my own ‘I was here memorial tablet'.

On the billboards alongside the bridge, there's an advertisement for luxury residences. The text reads: ‘The world allows those with foresight to get ahead'. Over the past forty years, the keyword in Chinese society has gone from ‘revolution’ to ‘success’, but the standards for attaining that success have become more and more narrowly defined. This is the ideology that has forced those who cannot ‘succeed’ to jump off the bridge. When I drove from Beijing to Nanjing, and crossed over the Yangtze River Bridge, I left behind a lengthy trail of messages that I had carved into the tires of my car, like a rubber stamp: This was the ‘Way of Failure’.

In the summer of 2008, I scratched off a suicide note written on the bridge in blood, and cut my own finger. I wrote, in my own blood, ‘Where is the capital of Madagascar?’. My calligraphy was poor. I was in pain, and my hand was shaking.

People ask me why I wrote that line. In fact, many people have wondered about that. I show them the picture of my work, The Countdown of 5000 A.D. When we are on the bridge, steaming in the sauna of failure, with no way out, we need something that is more remote than fate to provide comfort for our souls. The very opposite of The Countdown of 5000 A.D. is the countdown clock that was erected in Tiananmen Square for the 2008 Beijing Olympics, an absurd joke if there ever was one: a purely political joke.

fig. 5 Qiu Zhijie, SNJYRB No.106# : Love is dead...where is the capital of Madagascar? , Performance, photo-installation and video, 2008

fig. 6 Qiu Zhijie, The Countdown of 5000 A.D. , Installation, stainless steel with electronic components, 2009

So, the kind of work I do has come full circle. On the surface, it appears that saving people's lives on the bridge, teaching, and curating art exhibitions are all respectable forms of social engagement. Painting and calligraphy, on the other hand, are extremely private and personal practices; the closest one can come to self-cultivation. Chance and fate play a role in all my acts of social engagement. As I see, this is the same as the path of the traditional Confucian scholar: In poverty, do the best you can to preserve yourself; if you succeed, then spread your good fortune to others.

In fact, even the most superficial form of social involvement presents an opportunity to practice self-cultivation. The more time I spent on the bridge, the more idiosyncratic and dense my brushwork and imagery became, rather than falling repeatedly into traditional patterns. As my commitment to calligraphy and painting deepens, my soul grows more responsive and I acquire greater freedom.

Only when I am actually touching brush to paper, as if there were no turning back, does my calligraphy and painting give me inner strength, and the courage to visit the bridge repeatedly; these visits are in themselves a form of intervention. That may explain why, in my painting, I do not depict gnarled trees, forests in winter, pine trees, bubbling springs and elegant scholars in long robes. We eat meat, we don't practice meditation, and we worry constantly, and thus we are destined to go to hell. But because I have been omnivorous since I was a boy, in this regard I have nothing to fear.

Recently, I have been working on an art therapy programme for a group dedicated to preventing suicides on the Yangtze River Bridge. My daughter, Qiu Jiawa, is five years old, and it's time for her to start learning calligraphy. I've copied out the Taishan Diamond Sutra, and told her to trace the characters in her own hand over mine. I believe that calligraphy and painting, Tang and Song poetry, and Chinese characters will provide her with a good luck charm, a talisman that will enable her to survive any form of inferno.

In time, when our generation has passed on, Qiu Jiawa will copy out a text for her children, and tell them to trace the characters in their own hand.

Chinese people don’t believe in immortality. But the energy that is inside them, that is authentically theirs, never dies; it passes on down, from one generation to the next.