2023

Speech at the 8th Annual Conference on Network Society

First, I must explain that I am not an academic, I'm an engineer. And therefore, I will not attempt to make assertions that are based on fact, and they will be claims that I make, and I invite everybody to test those claims against real life. Because in engineering, you always work with imperfect tools and inadequate information, and you must therefore produce a result that will serve the necessary function, and that's always a matter of guesswork. So, I ask you to judge me or my assertions here on this basis.

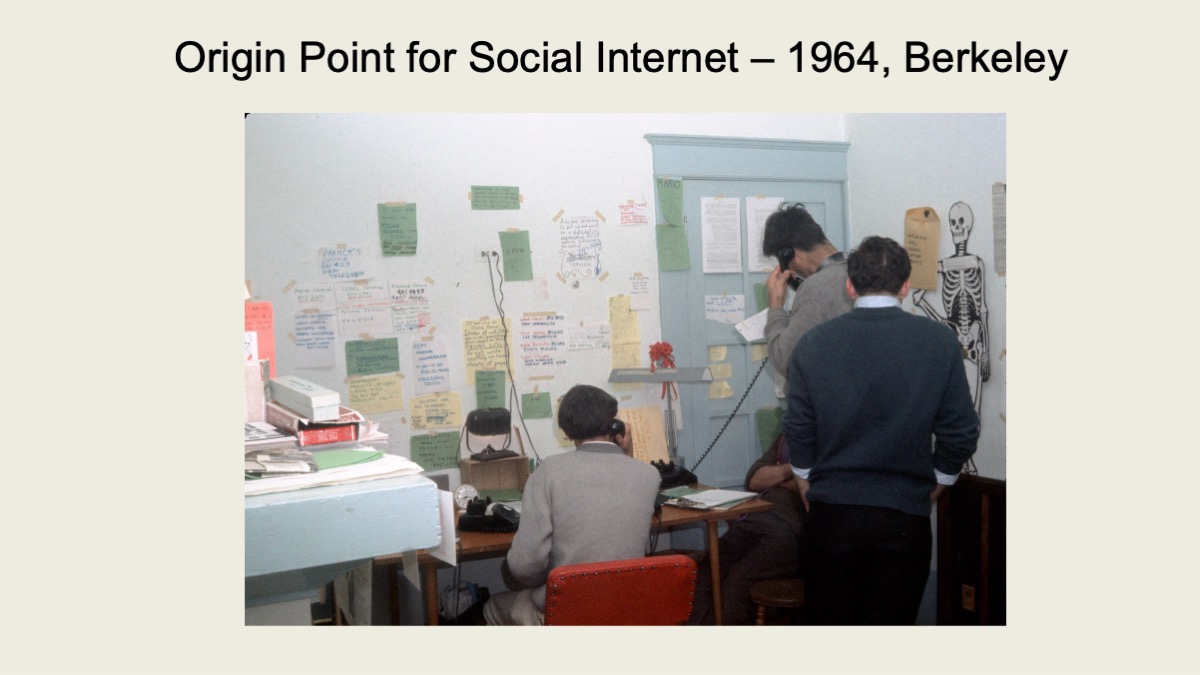

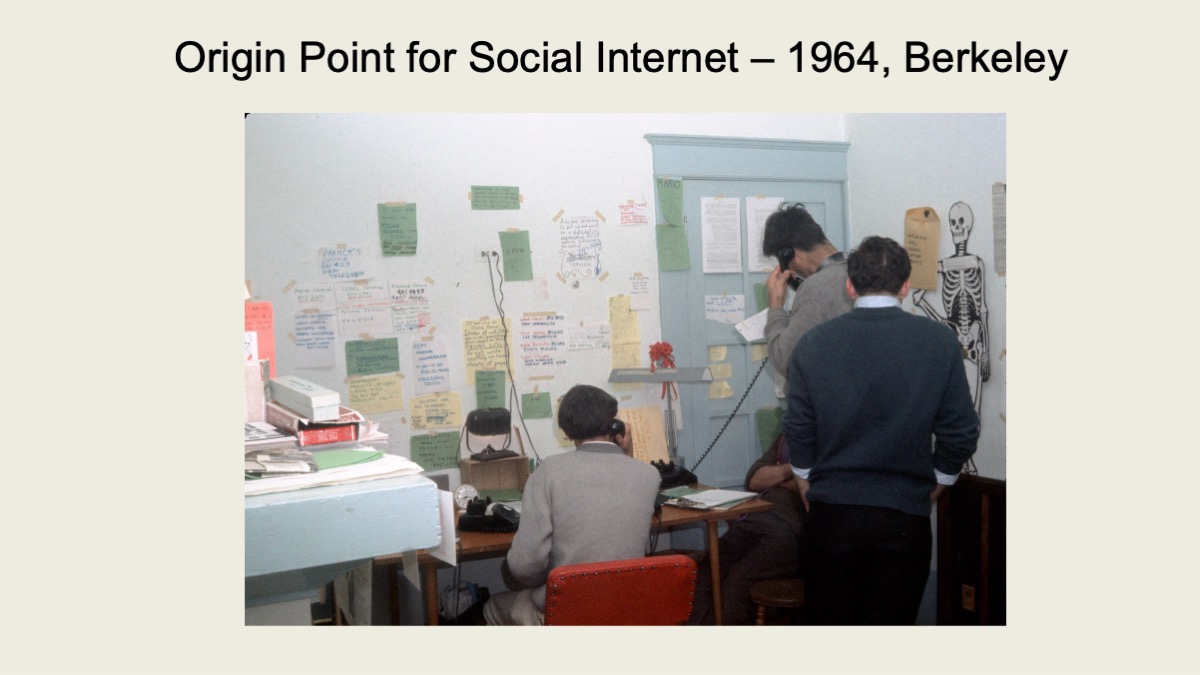

Now we see here a picture that I call “the origin point for the social internet”. In 1964 it is taken against the rules by myself in the office of the Free Speech Movement in Berkeley. Now, this doesn't look very computerized. It isn't. There's no computer in those days. There are just telephones. And it doesn't look very neat, doesn't look very efficient. But in this inefficiency, an outcome was developed, I think it is still redounding today. We see people busy listening to phones. There are only two telephones. And the items on the wall constitute the database, which was constantly changing as people called in.

Now a telephone room in a well-run company will have a good order and information will come in, it will be recorded, it would be categorized, it will be passed up to the necessary people. Information to go out or come in, and it would be a flow of information going both ways, all very orderly because the functioning of the business would rely upon that. That's not happening here.

People are calling in for various reasons. Sometimes they have information they wanted to pass on. Sometimes they have a question they wanted answered. Sometimes they wanted to offer a resource. I think in one of these notices, someone is offering haircuts for free. Because we were coming up on a time when the holidays would have people going home to face their parents, and often, they would need a haircut. So, and they also named it Haircut Central. We sort of have an approach of naming everything central. So this was within FSM Central. And all manner of connections are being made through this set of phones and this desk and these people, and you may well imagine that you can't just put any people in there. The information is in part in the heads of the people as well as on the walls.

Now the reason why this is important, it both for the immediate situation in 1964 and for the future, is that it was a part of a mechanism that allowed the campus community to form. Now, Berkeley is a big place. In those days, it was 20,000 students, today at 30,000. And it was notorious for alienation. You came there, you were all alone within a massive crowd. You didn't know anybody. They didn't know you and they didn't care. Now, when I got there, I actually liked that situation, but I'm a special case.

And at that time, the university issued a new rule. There were tables that these student groups had set up just outside of campus. There's a wall of posts on the sidewalk and thousands of people would stream past on the way in and out of the campus. And they could get information at these tables. They could give donations, they could sign up for participation in various things, including demonstrators in the galleries of the Republican National Convention that was held in San Francisco that year. And of course, there was the contention between the first of the, in effect, the MAGA Barry Goldwater and some moderate guy named William Scranton. And the local political boss was on the side of the MAGA, and he was not amused by students being recruited at these tables to come over to the San Francisco, to the convention and make noise against this candidate. And so, we understand, we don't have this in a literal proof that he put pressure and others put pressure on the administration because there were also protests underway to employment discrimination. And there were sit-ins. It was rather disorderly at that time.

So, the university was receiving pressure from outside. They issued this rule and it was a completely the wrong time to do it, because, again, civil rights was not a distant matter. It was not just in the South. It had come right into our front yard, and the students who came back from Freedom Summer were heavily involved. So, all of the student organizations from the far left to the far right, from the Maoist Progressive Labor Party to the libertarian—what was a society of individualists, something like that, they were to the right of the campus—Young Republicans or Cal Conservatives for Political Action, they all united as the united front to face this and to fight it.

And since the university had discovered that they actually owned the land on that sidewalk strip out much closer to the curb, we couldn't move the tables out so that tables had to go into campus. And we engaged in classical civil disobedience, strategy known as “filling the jails”. We set up tables right in front of the administration building. If it's going to be illegal to have it anywhere on campus, that's as good a place as any. And deans would come out and take names of students for disciplinary purposes. As soon as they took one person's name, another one would take their place, take my name too. And eventually in that day, when they were summoned to the dean's office, 150 students showed up, you know, punish us. They weren't able to do that. The next day was October 1st, the protest continued and the first non-student was cited. And this was like a gleeful opportunity for the university because a law had been passed in the last year that provided criminal penalties for anybody being on campus without being a registered student or faculty member. We got one. So they did the most stupid thing possible in the middle of the day, shortly before the vast torrent of people were to come past, they brought up a police car and they put this person, Jack Weinberg, in the police car. And what can you expect? Everybody started sit down and the police car was captured. And this grew and grew and lasted for 32 hours. Eventually, there were negotiations. There was some kind of arrangement made.

We went on it for two months till finally there was a climactic sit-in in the university building. I was involved, and 784 students were arrested. The faculty was shocked into recognizing the situation and in a few days, they voted in their faculty senate by a factor of 80% to support the student position. This provided the political support to cause the owners of the university, the regents too, back off and say, well, we're not going to interfere with this. So suddenly, the campus became open to any and all kinds of student activity, whether or not it was approved by the university. Prior to that point, you couldn't hand out a leaflet on campus unless it was approved. Now you could hand out anything you wanted.

I'm going to talk here about media structure because this got me thinking about it. I don’t mean it got me thinking about it right now. I mean it got me think about it in 1964. I was an engineering student. I adhere to the opinion, sort of vaguely left-wing opinion that my future task would be automation and replacing labor and that would somehow advance social progress. And I had a tried to attach myself to the FSM office because I didn't have any classes or homework. I was working on campus for that six-month period and my quest was to find out what I could do as a technologist because that's all I thought I could do. I was not going change anybody's mind, but I could build things. And I will talk at a later time about what happened there, but the result was that I went off on a path of exploration, trying to find what, especially what media technologies would be effective.

Now the reason to do this is that December was the last months of the academic year, January of 1965, the campus was amazing. All sorts of people were doing all sorts of things in all sorts of fields. This, we didn't expect. This was the opening of the counterculture, certainly in the Bay Area, there have been countercultures in the past, but the one we consider here is the counterculture of the 1960s. And I wrote some little essay which somebody published. And of course, this is not what young engineering students do. We usually keep our mouths shut. But people weren't keeping their mouth shut, and they weren't staying in one place. In fact, we can estimate that some thousands of students dropped out, left the university and turned up later in places like the Haight-Ashbury. They formed their own communities and that was the key to it all.

I want to go back to looking at the media structure. What I came up with around that time and shortly thereafter was an analysis of media into two categories, broadcast and non-broadcast. Broadcast media emits the same message from one to many. Now this can be on print, doesn't have to be in electromagnetic, and it can be done from noon rallies. We had noon rallies almost every day. Thousands of people would listen to what's going on about the crisis at the particular moment. We handed out leaflets. I helped produce those leaflets. That’s the one thing I was able to do. And people would come to the campus in the morning to take the leaflets we had turned out, and they would go out and they were risking discipline by doing so. And people knew that. Each of them became a focal point for discussion. People would come up to them and say, well, why are you doing this? What's up? What's going on? What do you think? We also had a subscriber-owned radio station in Berkeley, which I think advanced the entire process because we had a kind of feedback loop. It was possible to get information into that station. It was noncommercial and run by people mostly like us.

The non-broadcast medium were the discussions happening around the leafleteers. We also created an organizational structure with a large executive committee that really wasn't executive, but it had representatives from all living organizations and others. This provided a two-way information conduit. These people were involved in setting the policy and there was a steering committee that they elected, which handled the moment-to-moment decisions. And some of those members of the steering committee were, in fact, replaced during this struggle, which is a little unusual among revolutionary organizations. But we had this path going out to all these people that were the constituents. We also had people who worked in the student recreation center and the art studios. They would carry on discussion there. So we also had the telephone system and the information exchange on that, that counts as a non-broadcast medium.

We look at a telephone, symmetric, universally accessible, at least in where we were. And I've already discussed the questions, suggestions, offer resources. What the process was, I call cross-connection. Now, that is an actual telephone technology term. Everything in the phone system is neat, neat, neat, until it comes up to the point where everything has to be cross-connected from one set of wires to the other. That's a mess. There’s almost no way to do that this neat. So there were notes on the wall, that was a mess. But it was the cross-connection. And what happened here, you couldn’t go through the substantive discussions on the phone like that, on the phone room. They would have to cut it short. You can divide the information into two forms, primary and secondary. Primary information is the content that you need to convey, the lecture, the whole story. Secondary information is who they need to contact and how to contact them in order to get that whole story. So the telephone room was exchanging secondary information, and this worked.

I mentioned that we succeeded at our goals from the objective standpoint, and then we had the magic of January 1965. Some students started an outrageous new magazine and precursor to Rolling Stone. And advertised it with a gigantic spider[1] mobile hanging over their table. Well, they had to take that mobile down. We agreed that it was okay to have regulations on time, place, and manner. But our position had been, in reference to the U.S. Constitution, "First and Fourteenth or Fight", 1th amendment and 14th amendment. I can explain that in legalistic terms later. It’s not worth doing now. But when you have a nice slogan like that, you’ve got something. I mentioned how people were changing the direction of their lives. I was, too. And it was a magical feeling. I wanted life to be like that all the time. And so, resolve to find the technological tools to make the process regular, rational. But it’s a whole lifetime’s worth of work, as I found out.

So the telephone information exchanges continued. Within the counterculture, maybe we're called switchboards. That's not the proper telephone terminology, but it's who cares? And by 1969, there was a listing of all of them for all the various causes.

And the underground press that I just mentioned started in 1965 to report upon the anti-war demonstrations because the Vietnam War was heating up that year. So the anti-war activity followed and was made possible by the Free Speech Movement. It’s now called the alternative press and it continues. There’s no ending date on it. But these were little papers put out of houses and little offices. And I believe they could be a community media. So I went into them. I worked there as a writer. I learned journalism there. And I also saw what happened by the very structure of the media. They came loaded up with ads, personal ads, sex ads, and then display ads for sex matters. They made a lot of money for the publisher, but they were not community media anymore.

And so I learned the subscriber-owned radio station KPFA, established in 1949 by pacifist anti-war objectors who had been imprisoned and otherwise had to do government service during the war, and they decided that the media needs to change and we’ll set up a station that our listeners will own. Up on the FM band, the frequency modulation band, was just opening up at that time. So there were no listeners. They had to make their own listeners. They had to build their own radio set and offer it to subscribers. And they did.

And computer students began a project to bring the power of computers to the counterculture. And this is important because that’s where my path leads me. They formed an organization. They actually took over a corporate shell from a switchboard, a San Francisco switchboard, which was going dormant, and set it up as Resource One in 1970. And I heard about them just about the same time that I had reached a conclusion on my own that what I was looking for was a network of computers. And this is in 1970, you couldn’t run out and buy that. That was a big deal. And I remember saying, well, where am I going to get a computer? One year later, I was in that group, Resource One. They had secured the long-term loan, which is in effect the donation of not only a good mainframe computer, but the very same computer that had been used by Douglas Engelbart in 1968 for what is called “The Mother of All Demos”, where he demonstrated the personal use of computers, the big mainframe computer. But this was a bit of a genius bit of work. And when I heard about that demo, demonstration, I changed my thinking about what computers could do and how they could do it.

Now some observations, again, subject to question. People need a functioning community fulfilling to for a fulfilling life. I have a whole discussion on how that developed out of a Neolithic village, but I won't do that now. And a community can be defined as a group of people who communicate on a regular basis.

Now, some observations, again, subject to question. People need a functioning community for a fulfilling life. I have a whole discussion on how that developed out of a Neolithic village, but I won’t do that now. And a community can be defined as a group of people who communicate on a regular basis. Now, I’m going to introduce the term agora, which is not a new term. It’s Greek. It’s sort of the field where everybody hung out during the day. And the name derives from agon, the pain that the wrestlers felt when they were contending with each other. So in general, the agora is the place where information exchange occurs in public. This is very important. And people gain knowledge of who the other people are. So they become no longer isolated individuals. And this is where community forms. So that has been, we can see that in every community from antiquity. And the interesting question is how that developed. I mean, this is, let’s say that in a Neolithic village, civilization developed there, but not in the houses. It developed in the space between the houses, and that became the agora. So you find village squares, the Roman forums, Renaissance Piazza, the plain of Netherlands. It’s everywhere. And through cultural evolution, which occurs on a much more rapid basis than biological evolution, the need for the agora is built into every one of us. That’s something I’ll posit, and I can’t claim to have proved it.

The agora is a commons of information. In effect, I’m creating a kind of a definition here. And like all commons, it can be captured and exploited and enclosed. The agricultural commons of England and so forth were subject to that, and that was the beginning of capitalism. And it happened to the agora. First of all, literacy, print, people could write stuff down, read it to others, read it to themselves. You had to pay something for that, so it’s beginning to be privatized. And it’s gone all the way to the fact that our agora these days is the mass media, which is a broadcast phenomenon. An agora that I’ve been talking about is non-broadcast, and therein lies the rub. There’s where the change has to be made.

So we set up the first social media system. There was a Resource One, and it opened in 1973. We have had, with the help of hackers like Richard Greenblatt, we developed an information retrieval system that was not tied to a predetermined set of indexing words. You could create your own index word. You just enter it. The machine took care of the bookkeeping. And we set up terminals, technically without preloading them with data. Now, we did a little work to do that admittedly. It was not, it was complete zero. But otherwise, beyond that, all the media, all the content, this magical stuff called content, was provided by the users themselves. We did not advertise it. We simply set it up in a few places that people frequented. We had to choose the place fairly carefully, and when we moved it, other people would use it, and the people wouldn’t follow it. We found, discovered that out.

But it was successful because people did use it. And whereas we had assumed that there would only be a few categories like jobs, housing, and cars, in part because the paper bulletin boards of the university were divided into those areas, that supposition went out the window. It was a tremendous range of things, which included a learning exchange dialogue. And one can look at the writings of Ivan Illich, I-L-I-C-H, I may mention that here, who was important to me, but he had written a whole book about Deschooling Society in 1970 or 71. And at the end of it, he said, well, what can we have instead of schools? Well, maybe computers can be used to connect people who know things with people who want to learn them. Right?

And some of our people had seeded an item into the database saying, where can we find good bagels in the Bay Area? Now, I must explain here, a bagel is a toroidal roll, baked roll. I think it’s a Chinese invention. I’m not sure. And it became a Jewish specialty, which is mostly on the East Coast, and you couldn’t get many, there weren’t many places to get them in San Francisco. So two answers came in here. Here you can buy them, literally. And the third answer was the winner. And it said, if you call this phone number and ask for this name, a former bagel maker will teach you how to make bagels. We never found out if they actually did. So I like to say that we opened the door to cyberspace and found that it was hospitable territory. And the personal computer flowed out of this. We needed to have terminals that would work in public. There I was the hardware engineer. I didn’t know much software. And I began an investigation. And what came of this was preparation for the arrival of the personal computer in 1975. We also had social media developing elsewhere. The bulletin board systems using telephones — I’m going to skip through this — and the usual commercial networks.

Now, each of these examples — I can be asked legitimately, how much money did you make at this? And the answer is we didn’t make any money. It cost us money. For those who went in the direction of something that made income, as soon as they could get some money going, they stopped development. We were there to continue that development. And we can see today that social media has generated a number of problems. Tribalization, siloization of discourse, distortion of the polity — I mean, we’re living this in the U.S. right now — and a distraction. So, just one point. The technical model for how information is stored in most social media systems is the papyrus scroll. Not any more advanced than the Egyptians. And I’ll discuss that privately with anyone as to why that is.

So, we need to be able to plan an alternative direction. And we need to work out how to manage the commons of information. Every commons must have management. And it develops organically if the commons is to survive. There are people around who write books saying, oh, there’s a tragedy of the commons because everybody will be greedy and go for their maximum self-interest. No, no, that’s Adam Smith talking. That’s not the historical commons like fisheries, agricultural commons. Each of those have processes for self-management. We need to invent processes for self-management for the commons of information.

And one thing that I didn’t have the word for, I thought we had to have something called the inspectorate. And these are people who are empowered to investigate but not empowered to do anything about it. And it is finally a professor named Bernhard Pörksen in Germany writing a book, Digital Fever, who contacted me and asked me to write an introduction. He says this is journalism. That’s what we were missing. And he’s right. So, we need journalism.

Now, I suggest a model of public parks. People say, well, how’s it going to pay for itself? How do public parks pay for itself? They don’t. And they serve many of the functions of the agora. And I have been saying for years that the natural custodians of the commons of information are librarians, or at least people educated that way. And there’s the Internet Engineering Task Force, which has been working for decades on a voluntary basis to keep the Internet working, where there has been constant attempts to take them over by different private concerns, which are all rejected by the members because it’s workers’ power. These are the engineers who do the work. They’re going to not let somebody tell them what to do. And I think we’re there. I think we’re at the end.

So, I’m going to be trying to continue my work because people are now asking me, aren’t you sorry? I’m not sorry. We have much more work to do. And I think we can chart a course this way, which is not the course that’s going for what we call social media today. They’ll do their own thing. I’m not interested in stopping them. We couldn’t stop them. But we have to provide the structures, the culture, and the practices of self-management of our commons of information. And I can help. And I think you can, too. Thank you.

[1] Editor's note: Jackie Goldberg, Rich and Sue Currier, Andy Magid, Sandor Fuchs, Alice Huberman, Steve DeCanio and Jim Prickett had together begun publishing a fortnightly magazine. Since there were eight editors, and a spider has eight legs, they decided to call it Spider, and the ex post facto title was a strained acronym for Sex, Politics, International Communism, Drugs, Extremism and Rock 'n' Roll.

Speech at the 8th Annual Conference on Network Society

First, I must explain that I am not an academic, I'm an engineer. And therefore, I will not attempt to make assertions that are based on fact, and they will be claims that I make, and I invite everybody to test those claims against real life. Because in engineering, you always work with imperfect tools and inadequate information, and you must therefore produce a result that will serve the necessary function, and that's always a matter of guesswork. So, I ask you to judge me or my assertions here on this basis.

Now we see here a picture that I call “the origin point for the social internet”. In 1964 it is taken against the rules by myself in the office of the Free Speech Movement in Berkeley. Now, this doesn't look very computerized. It isn't. There's no computer in those days. There are just telephones. And it doesn't look very neat, doesn't look very efficient. But in this inefficiency, an outcome was developed, I think it is still redounding today. We see people busy listening to phones. There are only two telephones. And the items on the wall constitute the database, which was constantly changing as people called in.

Now a telephone room in a well-run company will have a good order and information will come in, it will be recorded, it would be categorized, it will be passed up to the necessary people. Information to go out or come in, and it would be a flow of information going both ways, all very orderly because the functioning of the business would rely upon that. That's not happening here.

People are calling in for various reasons. Sometimes they have information they wanted to pass on. Sometimes they have a question they wanted answered. Sometimes they wanted to offer a resource. I think in one of these notices, someone is offering haircuts for free. Because we were coming up on a time when the holidays would have people going home to face their parents, and often, they would need a haircut. So, and they also named it Haircut Central. We sort of have an approach of naming everything central. So this was within FSM Central. And all manner of connections are being made through this set of phones and this desk and these people, and you may well imagine that you can't just put any people in there. The information is in part in the heads of the people as well as on the walls.

Now the reason why this is important, it both for the immediate situation in 1964 and for the future, is that it was a part of a mechanism that allowed the campus community to form. Now, Berkeley is a big place. In those days, it was 20,000 students, today at 30,000. And it was notorious for alienation. You came there, you were all alone within a massive crowd. You didn't know anybody. They didn't know you and they didn't care. Now, when I got there, I actually liked that situation, but I'm a special case.

And at that time, the university issued a new rule. There were tables that these student groups had set up just outside of campus. There's a wall of posts on the sidewalk and thousands of people would stream past on the way in and out of the campus. And they could get information at these tables. They could give donations, they could sign up for participation in various things, including demonstrators in the galleries of the Republican National Convention that was held in San Francisco that year. And of course, there was the contention between the first of the, in effect, the MAGA Barry Goldwater and some moderate guy named William Scranton. And the local political boss was on the side of the MAGA, and he was not amused by students being recruited at these tables to come over to the San Francisco, to the convention and make noise against this candidate. And so, we understand, we don't have this in a literal proof that he put pressure and others put pressure on the administration because there were also protests underway to employment discrimination. And there were sit-ins. It was rather disorderly at that time.

So, the university was receiving pressure from outside. They issued this rule and it was a completely the wrong time to do it, because, again, civil rights was not a distant matter. It was not just in the South. It had come right into our front yard, and the students who came back from Freedom Summer were heavily involved. So, all of the student organizations from the far left to the far right, from the Maoist Progressive Labor Party to the libertarian—what was a society of individualists, something like that, they were to the right of the campus—Young Republicans or Cal Conservatives for Political Action, they all united as the united front to face this and to fight it.

And since the university had discovered that they actually owned the land on that sidewalk strip out much closer to the curb, we couldn't move the tables out so that tables had to go into campus. And we engaged in classical civil disobedience, strategy known as “filling the jails”. We set up tables right in front of the administration building. If it's going to be illegal to have it anywhere on campus, that's as good a place as any. And deans would come out and take names of students for disciplinary purposes. As soon as they took one person's name, another one would take their place, take my name too. And eventually in that day, when they were summoned to the dean's office, 150 students showed up, you know, punish us. They weren't able to do that. The next day was October 1st, the protest continued and the first non-student was cited. And this was like a gleeful opportunity for the university because a law had been passed in the last year that provided criminal penalties for anybody being on campus without being a registered student or faculty member. We got one. So they did the most stupid thing possible in the middle of the day, shortly before the vast torrent of people were to come past, they brought up a police car and they put this person, Jack Weinberg, in the police car. And what can you expect? Everybody started sit down and the police car was captured. And this grew and grew and lasted for 32 hours. Eventually, there were negotiations. There was some kind of arrangement made.

We went on it for two months till finally there was a climactic sit-in in the university building. I was involved, and 784 students were arrested. The faculty was shocked into recognizing the situation and in a few days, they voted in their faculty senate by a factor of 80% to support the student position. This provided the political support to cause the owners of the university, the regents too, back off and say, well, we're not going to interfere with this. So suddenly, the campus became open to any and all kinds of student activity, whether or not it was approved by the university. Prior to that point, you couldn't hand out a leaflet on campus unless it was approved. Now you could hand out anything you wanted.

I'm going to talk here about media structure because this got me thinking about it. I don’t mean it got me thinking about it right now. I mean it got me think about it in 1964. I was an engineering student. I adhere to the opinion, sort of vaguely left-wing opinion that my future task would be automation and replacing labor and that would somehow advance social progress. And I had a tried to attach myself to the FSM office because I didn't have any classes or homework. I was working on campus for that six-month period and my quest was to find out what I could do as a technologist because that's all I thought I could do. I was not going change anybody's mind, but I could build things. And I will talk at a later time about what happened there, but the result was that I went off on a path of exploration, trying to find what, especially what media technologies would be effective.

Now the reason to do this is that December was the last months of the academic year, January of 1965, the campus was amazing. All sorts of people were doing all sorts of things in all sorts of fields. This, we didn't expect. This was the opening of the counterculture, certainly in the Bay Area, there have been countercultures in the past, but the one we consider here is the counterculture of the 1960s. And I wrote some little essay which somebody published. And of course, this is not what young engineering students do. We usually keep our mouths shut. But people weren't keeping their mouth shut, and they weren't staying in one place. In fact, we can estimate that some thousands of students dropped out, left the university and turned up later in places like the Haight-Ashbury. They formed their own communities and that was the key to it all.

I want to go back to looking at the media structure. What I came up with around that time and shortly thereafter was an analysis of media into two categories, broadcast and non-broadcast. Broadcast media emits the same message from one to many. Now this can be on print, doesn't have to be in electromagnetic, and it can be done from noon rallies. We had noon rallies almost every day. Thousands of people would listen to what's going on about the crisis at the particular moment. We handed out leaflets. I helped produce those leaflets. That’s the one thing I was able to do. And people would come to the campus in the morning to take the leaflets we had turned out, and they would go out and they were risking discipline by doing so. And people knew that. Each of them became a focal point for discussion. People would come up to them and say, well, why are you doing this? What's up? What's going on? What do you think? We also had a subscriber-owned radio station in Berkeley, which I think advanced the entire process because we had a kind of feedback loop. It was possible to get information into that station. It was noncommercial and run by people mostly like us.

The non-broadcast medium were the discussions happening around the leafleteers. We also created an organizational structure with a large executive committee that really wasn't executive, but it had representatives from all living organizations and others. This provided a two-way information conduit. These people were involved in setting the policy and there was a steering committee that they elected, which handled the moment-to-moment decisions. And some of those members of the steering committee were, in fact, replaced during this struggle, which is a little unusual among revolutionary organizations. But we had this path going out to all these people that were the constituents. We also had people who worked in the student recreation center and the art studios. They would carry on discussion there. So we also had the telephone system and the information exchange on that, that counts as a non-broadcast medium.

We look at a telephone, symmetric, universally accessible, at least in where we were. And I've already discussed the questions, suggestions, offer resources. What the process was, I call cross-connection. Now, that is an actual telephone technology term. Everything in the phone system is neat, neat, neat, until it comes up to the point where everything has to be cross-connected from one set of wires to the other. That's a mess. There’s almost no way to do that this neat. So there were notes on the wall, that was a mess. But it was the cross-connection. And what happened here, you couldn’t go through the substantive discussions on the phone like that, on the phone room. They would have to cut it short. You can divide the information into two forms, primary and secondary. Primary information is the content that you need to convey, the lecture, the whole story. Secondary information is who they need to contact and how to contact them in order to get that whole story. So the telephone room was exchanging secondary information, and this worked.

I mentioned that we succeeded at our goals from the objective standpoint, and then we had the magic of January 1965. Some students started an outrageous new magazine and precursor to Rolling Stone. And advertised it with a gigantic spider[1] mobile hanging over their table. Well, they had to take that mobile down. We agreed that it was okay to have regulations on time, place, and manner. But our position had been, in reference to the U.S. Constitution, "First and Fourteenth or Fight", 1th amendment and 14th amendment. I can explain that in legalistic terms later. It’s not worth doing now. But when you have a nice slogan like that, you’ve got something. I mentioned how people were changing the direction of their lives. I was, too. And it was a magical feeling. I wanted life to be like that all the time. And so, resolve to find the technological tools to make the process regular, rational. But it’s a whole lifetime’s worth of work, as I found out.

So the telephone information exchanges continued. Within the counterculture, maybe we're called switchboards. That's not the proper telephone terminology, but it's who cares? And by 1969, there was a listing of all of them for all the various causes.

And the underground press that I just mentioned started in 1965 to report upon the anti-war demonstrations because the Vietnam War was heating up that year. So the anti-war activity followed and was made possible by the Free Speech Movement. It’s now called the alternative press and it continues. There’s no ending date on it. But these were little papers put out of houses and little offices. And I believe they could be a community media. So I went into them. I worked there as a writer. I learned journalism there. And I also saw what happened by the very structure of the media. They came loaded up with ads, personal ads, sex ads, and then display ads for sex matters. They made a lot of money for the publisher, but they were not community media anymore.

And so I learned the subscriber-owned radio station KPFA, established in 1949 by pacifist anti-war objectors who had been imprisoned and otherwise had to do government service during the war, and they decided that the media needs to change and we’ll set up a station that our listeners will own. Up on the FM band, the frequency modulation band, was just opening up at that time. So there were no listeners. They had to make their own listeners. They had to build their own radio set and offer it to subscribers. And they did.

And computer students began a project to bring the power of computers to the counterculture. And this is important because that’s where my path leads me. They formed an organization. They actually took over a corporate shell from a switchboard, a San Francisco switchboard, which was going dormant, and set it up as Resource One in 1970. And I heard about them just about the same time that I had reached a conclusion on my own that what I was looking for was a network of computers. And this is in 1970, you couldn’t run out and buy that. That was a big deal. And I remember saying, well, where am I going to get a computer? One year later, I was in that group, Resource One. They had secured the long-term loan, which is in effect the donation of not only a good mainframe computer, but the very same computer that had been used by Douglas Engelbart in 1968 for what is called “The Mother of All Demos”, where he demonstrated the personal use of computers, the big mainframe computer. But this was a bit of a genius bit of work. And when I heard about that demo, demonstration, I changed my thinking about what computers could do and how they could do it.

Now some observations, again, subject to question. People need a functioning community fulfilling to for a fulfilling life. I have a whole discussion on how that developed out of a Neolithic village, but I won't do that now. And a community can be defined as a group of people who communicate on a regular basis.

Now, some observations, again, subject to question. People need a functioning community for a fulfilling life. I have a whole discussion on how that developed out of a Neolithic village, but I won’t do that now. And a community can be defined as a group of people who communicate on a regular basis. Now, I’m going to introduce the term agora, which is not a new term. It’s Greek. It’s sort of the field where everybody hung out during the day. And the name derives from agon, the pain that the wrestlers felt when they were contending with each other. So in general, the agora is the place where information exchange occurs in public. This is very important. And people gain knowledge of who the other people are. So they become no longer isolated individuals. And this is where community forms. So that has been, we can see that in every community from antiquity. And the interesting question is how that developed. I mean, this is, let’s say that in a Neolithic village, civilization developed there, but not in the houses. It developed in the space between the houses, and that became the agora. So you find village squares, the Roman forums, Renaissance Piazza, the plain of Netherlands. It’s everywhere. And through cultural evolution, which occurs on a much more rapid basis than biological evolution, the need for the agora is built into every one of us. That’s something I’ll posit, and I can’t claim to have proved it.

The agora is a commons of information. In effect, I’m creating a kind of a definition here. And like all commons, it can be captured and exploited and enclosed. The agricultural commons of England and so forth were subject to that, and that was the beginning of capitalism. And it happened to the agora. First of all, literacy, print, people could write stuff down, read it to others, read it to themselves. You had to pay something for that, so it’s beginning to be privatized. And it’s gone all the way to the fact that our agora these days is the mass media, which is a broadcast phenomenon. An agora that I’ve been talking about is non-broadcast, and therein lies the rub. There’s where the change has to be made.

So we set up the first social media system. There was a Resource One, and it opened in 1973. We have had, with the help of hackers like Richard Greenblatt, we developed an information retrieval system that was not tied to a predetermined set of indexing words. You could create your own index word. You just enter it. The machine took care of the bookkeeping. And we set up terminals, technically without preloading them with data. Now, we did a little work to do that admittedly. It was not, it was complete zero. But otherwise, beyond that, all the media, all the content, this magical stuff called content, was provided by the users themselves. We did not advertise it. We simply set it up in a few places that people frequented. We had to choose the place fairly carefully, and when we moved it, other people would use it, and the people wouldn’t follow it. We found, discovered that out.

But it was successful because people did use it. And whereas we had assumed that there would only be a few categories like jobs, housing, and cars, in part because the paper bulletin boards of the university were divided into those areas, that supposition went out the window. It was a tremendous range of things, which included a learning exchange dialogue. And one can look at the writings of Ivan Illich, I-L-I-C-H, I may mention that here, who was important to me, but he had written a whole book about Deschooling Society in 1970 or 71. And at the end of it, he said, well, what can we have instead of schools? Well, maybe computers can be used to connect people who know things with people who want to learn them. Right?

And some of our people had seeded an item into the database saying, where can we find good bagels in the Bay Area? Now, I must explain here, a bagel is a toroidal roll, baked roll. I think it’s a Chinese invention. I’m not sure. And it became a Jewish specialty, which is mostly on the East Coast, and you couldn’t get many, there weren’t many places to get them in San Francisco. So two answers came in here. Here you can buy them, literally. And the third answer was the winner. And it said, if you call this phone number and ask for this name, a former bagel maker will teach you how to make bagels. We never found out if they actually did. So I like to say that we opened the door to cyberspace and found that it was hospitable territory. And the personal computer flowed out of this. We needed to have terminals that would work in public. There I was the hardware engineer. I didn’t know much software. And I began an investigation. And what came of this was preparation for the arrival of the personal computer in 1975. We also had social media developing elsewhere. The bulletin board systems using telephones — I’m going to skip through this — and the usual commercial networks.

Now, each of these examples — I can be asked legitimately, how much money did you make at this? And the answer is we didn’t make any money. It cost us money. For those who went in the direction of something that made income, as soon as they could get some money going, they stopped development. We were there to continue that development. And we can see today that social media has generated a number of problems. Tribalization, siloization of discourse, distortion of the polity — I mean, we’re living this in the U.S. right now — and a distraction. So, just one point. The technical model for how information is stored in most social media systems is the papyrus scroll. Not any more advanced than the Egyptians. And I’ll discuss that privately with anyone as to why that is.

So, we need to be able to plan an alternative direction. And we need to work out how to manage the commons of information. Every commons must have management. And it develops organically if the commons is to survive. There are people around who write books saying, oh, there’s a tragedy of the commons because everybody will be greedy and go for their maximum self-interest. No, no, that’s Adam Smith talking. That’s not the historical commons like fisheries, agricultural commons. Each of those have processes for self-management. We need to invent processes for self-management for the commons of information.

And one thing that I didn’t have the word for, I thought we had to have something called the inspectorate. And these are people who are empowered to investigate but not empowered to do anything about it. And it is finally a professor named Bernhard Pörksen in Germany writing a book, Digital Fever, who contacted me and asked me to write an introduction. He says this is journalism. That’s what we were missing. And he’s right. So, we need journalism.

Now, I suggest a model of public parks. People say, well, how’s it going to pay for itself? How do public parks pay for itself? They don’t. And they serve many of the functions of the agora. And I have been saying for years that the natural custodians of the commons of information are librarians, or at least people educated that way. And there’s the Internet Engineering Task Force, which has been working for decades on a voluntary basis to keep the Internet working, where there has been constant attempts to take them over by different private concerns, which are all rejected by the members because it’s workers’ power. These are the engineers who do the work. They’re going to not let somebody tell them what to do. And I think we’re there. I think we’re at the end.

So, I’m going to be trying to continue my work because people are now asking me, aren’t you sorry? I’m not sorry. We have much more work to do. And I think we can chart a course this way, which is not the course that’s going for what we call social media today. They’ll do their own thing. I’m not interested in stopping them. We couldn’t stop them. But we have to provide the structures, the culture, and the practices of self-management of our commons of information. And I can help. And I think you can, too. Thank you.

[1] Editor's note: Jackie Goldberg, Rich and Sue Currier, Andy Magid, Sandor Fuchs, Alice Huberman, Steve DeCanio and Jim Prickett had together begun publishing a fortnightly magazine. Since there were eight editors, and a spider has eight legs, they decided to call it Spider, and the ex post facto title was a strained acronym for Sex, Politics, International Communism, Drugs, Extremism and Rock 'n' Roll.