2013

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

——William Yeats, The Second Coming.

What are we waiting for? What awaits us?

——Ernst Bloch, The Principle of Hope

Why do we reflect on “Reflecta ?” Because the histories of music, cinema, theater, literature, and architecture have each obscured the histories of sound, video, the body, writing, and construction and dwelling…

Reflecta

On the eve of the millennium as the whole world was convulsed in clamor and celebration, I sat alone at my desk and for the first time truly perceived the great power of the changes of the era and the course of time. As wave after wave of chill and darkness battered the window pane, I wrote the following:

At one in the morning

I trace the fingerprint

Of God;

The shape of Time

Is a wave, like

A ring of mountains trembling in the dark;

Amid the weary sighs of the ocean,

They rise, roll,

Crash and break:

Day after day, night after night.

For many years afterward the feelings that moved me so deeply that night would return, beyond my control. The inexplicable sensation does not belong entirely to “history,” because that term has long since become an academic, scripted tool manipulated by experts as a part of the modern process of knowledge production – with its disciplines and bureaucracy. History has become detached from our experience. What I felt on the last night of the twentieth century was that nameless “Reflecta.” Our “world” means our place of exile for a time: on that turning point between the old century and the new, the nameless Reflecta swelled, dissipated, and transformed: it was invisible, intangible, and infinite.

This nameless “Reflecta” has always pulled my thoughts, causing my thinking about history to always be entangled in the “sense of history” rather than the “view of history.” Only recently has this sense of history gradually crystallized into a vision: it is an ocean of history, undulating and tumultuous, shuttles back and forth inside and outside our bodies. What we know as the “contemporary” is merely the surface of the randomly emerging sea: the “surface” mirage, however, is inseparable from that great watery expanse.

How, then, does this ocean of history become a “Reflecta,” and where is this nameless Reflecta headed?

In today's intellectual context and living atmosphere, this line of thinking seems irrelevant and unsuitable for its time. Caught up in everyday life, most of the time we only give thought to our ambitions and personal interest and only deal with the ordinary and trivial. This is why some call our age a “tiny” era. Intoxicated by and dreaming about this tiny era, the so-called “Kidult” generation surrenders the possibilities of poetry and creation in life to the production and consumption of subcultures. Therefore, whether it's individualism or youthful dreams, everything is absorbed into a ready-made posture and emotion, no longer able to challenge our emotional structure, let alone initiate any social imagination or historical plan. In this tiny era, everyone is obsessed by the one-size-fits-all mundane happiness of what Nietzsche termed the “Last Man” rendering any grand narrative and construction inevitably a mockery.

However, even today, I am still willing to believe that any age can be a great era despite the way every generation tends to laud the glory of former days. Time never stops, and the progress of history remains the same. The nameless “Reflecta” behind history awaits a grand vision and narrative that can match it.

Base

WestBund 2013 was inspired by a desire to explore “Reflecta.” Reflecta has been demonstrated on the West Bund firstly as a sort of rejuvenation: this narrow strip of land beside the Huangpu River was “rediscovered” because of the 2010 Shanghai Expo. What remains on the land are the memories of Shanghai’s modern heavy industry: the wharves, train station, airport and cement factories that produced the basic materials of the urban fabric...With the Shanghai Expo, these relics of old industry were incorporated into the city’s large-scale urban renewal and Fabrica plan, becoming a piece of "land" that has been revitalized and yet to be defined.

Globally, the West Bund (Bank) may not stand out as a repository of the memories of modern industry. For half a century, a great number of industrial ruins have been constantly corroding Europeans’ image of everyday life. Throughout the process, the deserted centers of modern industry are becoming ruins and monuments marking the passage of time. The process fits in nicely with the logic of modernity and was remarked on by Walter Benjamin in the swift dilapidation of the Paris arcade: modernity describes the way new things swiftly become emblems of the old and outdated – today’s progress outstrips yesterday’s. Modernity is constantly being betrayed by the “now.” “Modern” is merely a traveler constantly being ferried across the irreversible river of time. It was precisely this fact that led Walter Benjamin to compare the great 19th century to the “last refuge of infant prodigies.” Modernity that constantly develops also constantly creates old-fashioned and out-of-date modernity. Therefore, no era has a more urgent need for memory than modern times. Therefore, paradoxically, museums, historical studies, archival systems and nostalgia have become important symbols of modernity.

How can we get beyond a deterministic, teleological and progressionist illusion of history, while avoiding wasteful commemoration and nostalgia? How can we redraw a productive vision of the future from the ruins of modernity? What is required is another visit to this repository of memories: we have to listen, observe, and experience.

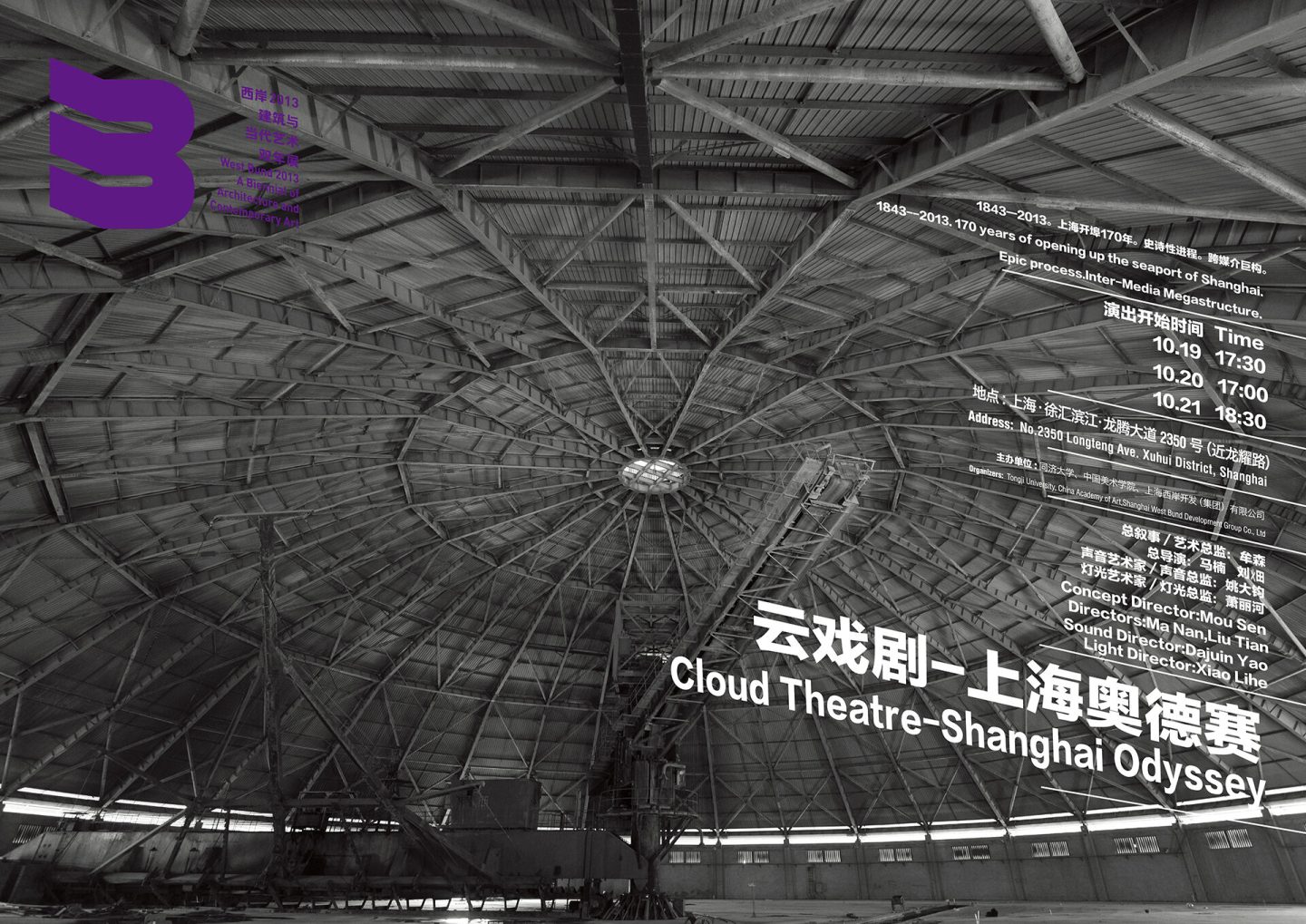

One autumn evening in 2012, I faced the great dome of the old pre-homogenization studio for the first time: it was like a UFO that had dropped from outer space, or the skeleton of the Behemoth, resting on the bank of the Huangpu River, or beached on the riverbed of Time. “The fragrant pasture that buries the hero, a sunset land that whiles away the years of his life.” Entering the darkness of the dome I sensed again the flow of history and the inscrutable Reflecta.

The cement works site remains still, and its soul has not yet departed. The thoughts of countless people through the ages, the assembly and movement of their bodies, their hopes and lives, toil, and labor, continue to swirl around and mix in this huge space of ruins. The momentum and sluggish dragging of history, the ebb and flow of the times, the life or death of a city, and the fortunes and misfortunes of countless individuals, all converge within the industrial actions contained in this cavern and its domed roof. Their entirety forms a sort of force of destiny that continues to swirl and churn, defying explanation, wheat inseparable from chaff.

Spatially, this great cement-mixing workshop bears a striking resemblance to the Pantheon of ancient Rome. However, the tremendous, cyclical force of history at play here neither originates from nor aims toward the Roman-esque infinite perspective of the sky. In the symbology of European domed architecture, the pinnacle of that perspective originally pointed to God, whose gaze looked down from Heaven and pierced all of existence. Everywhere touched by his gaze was touched by his power as well. People were merely observed and "watched." In his works written after he lost his sight, Jorge Luis Borges often mentioned the infinitely transparent blue sky: “a skylight lets us into the true abyss.” Looking through the hole above our heads we see an infinite abyss in which there hides an infinitely transparent (and therefore invisible to us) real world: “Everything happens and nothing is recorded/In these rooms of the looking-glass.”

In the context of WestBund 2013, “Reflecta” seeks to demystify first of all the divine aspect of the dome roof. It has nothing to do with metaphysical tenets: it refers purely to the people’s destiny, to human history and human memory. The power of destiny and the history and memories here float around the great space, sometimes apparent, sometimes not, waiting for us to listen, observe and experience.

Eisenstein once said that old cinema sought to express a single storyline from many different angles, while new cinema presents a single perspective through multiple storylines. Listening, observation and experiencing — these three actions correspond to the three main artistic threads in the thematic exhibition: the sound, video and theater aspects of Chinese contemporary art since the new millennium. The three elements serve as contexts for each other, developing independently while converging into a unique social force that reflects the historical process and trajectory from different angles.

Listening

A century ago, the futurist artist Luigi Russolo pioneered the age of modern sound art with his Intonarumori (intoning devices). From that point on, industrial machinery and the metropolis have become significant themes of sound performances; furthermore, musical sound’s opposing force – noise – began to produce its own perceptive torrent and creative power.

However, a hundred years later, WestBund 2013 sees sound foremost as a method of testing the site. In the vast, six thousand square meters of cavernous, circular ruins, the first sound we hear is that of “silence.” “Where word breaks off no thing may be, ” and silence is not simply the absence of sound. Silence is an intrinsic part of human language and music; it is the foundation that makes all speech and sound possible. However, silence as a listening experience has been permanently lost amidst the constant background noise and clamor of the modern metropolis. The sound of the city has detached itself from its original time and space, being transmitted, replicated, echoed, and layered endlessly through modern media system. Sound no longer begins in silence nor fades into it. It can no longer return to silence, only be shifts and dispersed among other discourses and sounds.

Nevertheless, in the darkness of the dome, that long-lost silence seems to reappear. Here, silence represents the part of history that lingers in the shadows: the circulation of air, the faint rustling of litter, the whirring of machinery through time, the murmurs of workers; all these merges into the "resonance" of silence. Through this "resonance" of the ages we then hear the distant clamor of the mundane world and the agitation of the city's sounds. Every modern city is a sound theater, and in China's sound history, Shanghai is undoubtedly the most spectacular one. From the blaring of boat horns on the Huangpu River to trams, from the singing and dancing at the Paramount to the cries of peddlers in the alleyways, from Cultural Revolution-era propaganda to Shanghainese stand-up comedy ... all these varied forms come together, fragments of sound mixing with those of everyday life, creating Shanghai’s ever-present soundscape and its unique sound culture.

If we set aside for a moment the ocean of sound phenomena, can we distinguish the whispers of history and rumble of a transforming society? As an important component of the Reflecta section, the sound art exhibition curated by Dajuin Yao, titled "RPM," explores the "revolutions per minute" in the current sound reality. Revolutions happen in a snapshot: they are a reversal as well as new beginning. In an age of CDs, sound depends on the revolutions of a disc to be heard. The revolutions every minute and every instant give birth to the sound revolution, which is then put into an endless loop. This is the sound exhibition’s response to “Reflecta.” It is hoped to derive a political economy of sound from the creation and contemplation of Chinese sound art, thereby fostering a social listening experience and a society attuned to listening.

Observation

The reality on the screen is a watched reality, while the reality around us is an unseen one that surrounds us. The world presented on-screen is the “seen world,” or in other words the“visible world.” It is also the world that is “watched and used for watching .”

The audience focuses on those images that are inflated and see them as a separate world in which their moods oscillate from the peak of happiness to the trough of gloom in an instant. At the same time, the audience lives on in an everyday reality they have difficulty facing up to. The Everyday is scattered and yet endless, inscrutable, whereas the images provide a way to face the world. “Perspective can perhaps no longer represent the distance between myself and the world; it determines the position of the world with me at the center, putting the world before my eyes, making me forget the world is also behind me and that I am a part of it. The video camera also allows observation of the world from without.” These words of Stanley Cavell are right on the mark. The secret of cinema lies in its representation of a desired vision, one that is severed from our continuous experience and thus can be fully grasped. We observe the cinematic world in obedient comfort; it has long been objectified and represented by another eye external to the world, so it is a “seen world.”

It is this “seen world,” this "watched and watching world," that defines us as mere spectators and increasingly erodes our capacity as producers. This spectacle of video is precisely what the video art special exhibition Resolution Power aims to critique and resist. Curated by Guo Xiaoyan and Liu Xiao, the exhibition posits that the resolving power of video is not just about making reality clearer, but about returning that clear and definite image of reality to an indeterminate state. In the media age, we can no longer directly deal with reality itself: instead we must deal with and observe a pre-expressed, pre-packaged image of reality. The "resolution" of reality images is not just about interpretation, but more importantly, about deconstruction.

And the power of deconstruction comes from the ability to transform images into actions. The video special exhibition aims to call forth a “performative video” that does not rely on the techniques of “direct cinema” (using video to take action), but rather about making the image itself become the action.

Performative video with resolving power is not a new form of image but rather a form of video mobilization, continually reminding us of the intrinsic relationship between image and perception. Life and action are unshowable, just as the most fundamental video can only occur once – Pasolini said that a person's life is just one long take. Video as experience is continually developing and being experienced. It is isomorphic with our lives and, therefore, has the potential to continuously reconstructour relationship with reality.

It is a challenge to find moments in the current art history narrative where video becomes performative. Artist Chen Chieh-Jen once recounted an obscure moment in image history during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan (1895-1945). Japanese colonizers showed Japanese-language films as part of a propaganda drive inspiring loyalty to Emperor Hirohito. Since most Taiwanese could not understand Japanese, local interpreters, known as " Benshi (弁士)," were recruited to transmit the message of the films to their audience as they were broadcast. Many of those benshi had been members of the resistance and would often seize the opportunity to misinterpret the film subtitles into anti-Japanese propaganda instead. The resulting impression in the mind of the audience was a curious hybrid: Japanese propaganda plus speeches of defiance against the same material. The whole experience left the Taiwanese audience with a paradoxical image in their minds.

A second instance of a poignant video moment was early during the Civil War (1945-1949) in the remote area warzones of Shanxi, Hebei, Shandong, and Henan. At that time film was coming to play an ever more important role in the war effort, with visual information of the entire war zone being disseminated to every soldier and civilian through temporary exhibitions on street corners and in barracks, as well as photo albums passed around in trenches. Taking photographs was a significant event in the life of the troops. Before launching an assault, the accompanying photographers would take pictures of each member of the dare-to-die squad. It was a solemn moment in their lives – perhaps their last. The soldiers vaguely knew that due to material shortages, the cameras might not even contain film. Nevertheless, they dressed their best for the occasions, faced the lens, took their positions, and after taking the last and possibly only photo in their lives, charged into the perilous battlefield.

Those moments – whether it was the benshi used imperialization films for anti-Japanese propaganda during the Japanese occupation or the photographers in the trenches raised empty cameras to take pictures of soldiers before charging – are important moments in the history of Chinese imagery. The film where visuals and sounds were paradoxically opposed, and the filmless photography ritual before the assault, allow us to consider the essence of video from another perspective. These images, transmitted and accumulated in the minds of the people, gradually produced a liberating energy, transforming into the courage to act..

Resolution, as a performative video, does not mean only the use of video to call forth action in real life. More importantly, it calls on us to liberate ourselves from the passive position of spectators and to become producers of images once again. To do so we must reclaim our creative ability that has been wrested from our grasp. Here, “video” is a verb; it means to interact with and perceive video in the most personal way, to reflect on oneself through the process of video production, and to create new ruptures and poetics in the dialectic of life-action and personal-reflection. In the unfolding of this new poetics, images become actions, experiences are no longer ready-made, perception remains sensitive, and the world becomes vibrant once again. In this way, the performative video that resolution points the way to will not merely be “the video of producers” but also a “liberated” video.

Epilogue

What kind of era do we live in?

An era where nobody is satisfied with themselves, except in political propaganda. Therefore, The Other Bank has become an “existentialist part “of our lives. However, nowadays even dreams have become tools of ideology; even “the other bank” and utopia have become consumer products of the Society of the Spectacle. As a form of life governance, spectacle entails a segmentation and reallocation of our sensibility. It is the mechanism by which the objects we perceive/experience are “packaged.” Having these objects of our experience pre-packaged is the very core of contemporary consumer society; as one of the principles of a consumerist society, it entails the reduction of human desire and hope, and the deprivation of human imagination and potential. In the face of this I have repeatedly discussed this: in this age of spectacular capitalism, the "exploitation” of people’s labor value by the productive relationship has transformed into a bio-political deprivation of people’s ability to act.

What kind of process or Reflecta are we involved in?

What was that torrential and nameless Reflecta I felt the instant I walked into the huge cavernous space on the eve of the millennium? That Reflecta transcended any self- perception bounded by our current generation as well as the causality and descriptions that historians attempt to capture. It was an inexplicable and nameless Reflecta without a specific goal or direction – and yet it was as unstoppable as destiny.

One hundred and seventy years ago, Shanghai was opened as a treaty port and this great city began its path to modernity. In the present day when we look back on, experience and decipher the memories and past of the city, the images of the masses, the shadows of empires, the splendid spectacle of modern civilization, and the legends and dreams of the nation-state weave together in a glorious tapestry. The Shanghai of old, with its foreign settlements, the debates about East and West, colonization and de-colonization, revolution and post-revolution, social awakening and national independence, the Cultural Revolution and Reform and Opening Up – this Reflecta, entangled with the gestures and movements of countless people, the overlap of shadows and images, the reverberation of sounds and voices, and the mixture of good and bad, reflecting the struggles and quest for a better life, and the vicissitudes of that life, of the Chinese people over more than a century. Trapped in this complicated and yet majestic Reflecta, how do we deal with it? What can art do?

Finally, I remind myself once again that the age we live in is a great age. Furthermore, we are lucky to live on the cusp of a new age. Although that age has not yet arrived, and although it is no more than a temporary image in a great Reflecta and whose meaning will be continually rewritten and interpreted by history, the historical subjects within this Reflecta are unafraid to become like the caged beasts in Rilke's Panther:

As he paces in cramped circles, over and over,

the movement of his powerful soft strides

is like a ritual dance around a center

in which a mighty will stands paralyzed.

Translated by Steven HUANG, George Flemming

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

——William Yeats, The Second Coming.

What are we waiting for? What awaits us?

——Ernst Bloch, The Principle of Hope

Why do we reflect on “Reflecta ?” Because the histories of music, cinema, theater, literature, and architecture have each obscured the histories of sound, video, the body, writing, and construction and dwelling…

Reflecta

On the eve of the millennium as the whole world was convulsed in clamor and celebration, I sat alone at my desk and for the first time truly perceived the great power of the changes of the era and the course of time. As wave after wave of chill and darkness battered the window pane, I wrote the following:

At one in the morning

I trace the fingerprint

Of God;

The shape of Time

Is a wave, like

A ring of mountains trembling in the dark;

Amid the weary sighs of the ocean,

They rise, roll,

Crash and break:

Day after day, night after night.

For many years afterward the feelings that moved me so deeply that night would return, beyond my control. The inexplicable sensation does not belong entirely to “history,” because that term has long since become an academic, scripted tool manipulated by experts as a part of the modern process of knowledge production – with its disciplines and bureaucracy. History has become detached from our experience. What I felt on the last night of the twentieth century was that nameless “Reflecta.” Our “world” means our place of exile for a time: on that turning point between the old century and the new, the nameless Reflecta swelled, dissipated, and transformed: it was invisible, intangible, and infinite.

This nameless “Reflecta” has always pulled my thoughts, causing my thinking about history to always be entangled in the “sense of history” rather than the “view of history.” Only recently has this sense of history gradually crystallized into a vision: it is an ocean of history, undulating and tumultuous, shuttles back and forth inside and outside our bodies. What we know as the “contemporary” is merely the surface of the randomly emerging sea: the “surface” mirage, however, is inseparable from that great watery expanse.

How, then, does this ocean of history become a “Reflecta,” and where is this nameless Reflecta headed?

In today's intellectual context and living atmosphere, this line of thinking seems irrelevant and unsuitable for its time. Caught up in everyday life, most of the time we only give thought to our ambitions and personal interest and only deal with the ordinary and trivial. This is why some call our age a “tiny” era. Intoxicated by and dreaming about this tiny era, the so-called “Kidult” generation surrenders the possibilities of poetry and creation in life to the production and consumption of subcultures. Therefore, whether it's individualism or youthful dreams, everything is absorbed into a ready-made posture and emotion, no longer able to challenge our emotional structure, let alone initiate any social imagination or historical plan. In this tiny era, everyone is obsessed by the one-size-fits-all mundane happiness of what Nietzsche termed the “Last Man” rendering any grand narrative and construction inevitably a mockery.

However, even today, I am still willing to believe that any age can be a great era despite the way every generation tends to laud the glory of former days. Time never stops, and the progress of history remains the same. The nameless “Reflecta” behind history awaits a grand vision and narrative that can match it.

Base

WestBund 2013 was inspired by a desire to explore “Reflecta.” Reflecta has been demonstrated on the West Bund firstly as a sort of rejuvenation: this narrow strip of land beside the Huangpu River was “rediscovered” because of the 2010 Shanghai Expo. What remains on the land are the memories of Shanghai’s modern heavy industry: the wharves, train station, airport and cement factories that produced the basic materials of the urban fabric...With the Shanghai Expo, these relics of old industry were incorporated into the city’s large-scale urban renewal and Fabrica plan, becoming a piece of "land" that has been revitalized and yet to be defined.

Globally, the West Bund (Bank) may not stand out as a repository of the memories of modern industry. For half a century, a great number of industrial ruins have been constantly corroding Europeans’ image of everyday life. Throughout the process, the deserted centers of modern industry are becoming ruins and monuments marking the passage of time. The process fits in nicely with the logic of modernity and was remarked on by Walter Benjamin in the swift dilapidation of the Paris arcade: modernity describes the way new things swiftly become emblems of the old and outdated – today’s progress outstrips yesterday’s. Modernity is constantly being betrayed by the “now.” “Modern” is merely a traveler constantly being ferried across the irreversible river of time. It was precisely this fact that led Walter Benjamin to compare the great 19th century to the “last refuge of infant prodigies.” Modernity that constantly develops also constantly creates old-fashioned and out-of-date modernity. Therefore, no era has a more urgent need for memory than modern times. Therefore, paradoxically, museums, historical studies, archival systems and nostalgia have become important symbols of modernity.

How can we get beyond a deterministic, teleological and progressionist illusion of history, while avoiding wasteful commemoration and nostalgia? How can we redraw a productive vision of the future from the ruins of modernity? What is required is another visit to this repository of memories: we have to listen, observe, and experience.

One autumn evening in 2012, I faced the great dome of the old pre-homogenization studio for the first time: it was like a UFO that had dropped from outer space, or the skeleton of the Behemoth, resting on the bank of the Huangpu River, or beached on the riverbed of Time. “The fragrant pasture that buries the hero, a sunset land that whiles away the years of his life.” Entering the darkness of the dome I sensed again the flow of history and the inscrutable Reflecta.

The cement works site remains still, and its soul has not yet departed. The thoughts of countless people through the ages, the assembly and movement of their bodies, their hopes and lives, toil, and labor, continue to swirl around and mix in this huge space of ruins. The momentum and sluggish dragging of history, the ebb and flow of the times, the life or death of a city, and the fortunes and misfortunes of countless individuals, all converge within the industrial actions contained in this cavern and its domed roof. Their entirety forms a sort of force of destiny that continues to swirl and churn, defying explanation, wheat inseparable from chaff.

Spatially, this great cement-mixing workshop bears a striking resemblance to the Pantheon of ancient Rome. However, the tremendous, cyclical force of history at play here neither originates from nor aims toward the Roman-esque infinite perspective of the sky. In the symbology of European domed architecture, the pinnacle of that perspective originally pointed to God, whose gaze looked down from Heaven and pierced all of existence. Everywhere touched by his gaze was touched by his power as well. People were merely observed and "watched." In his works written after he lost his sight, Jorge Luis Borges often mentioned the infinitely transparent blue sky: “a skylight lets us into the true abyss.” Looking through the hole above our heads we see an infinite abyss in which there hides an infinitely transparent (and therefore invisible to us) real world: “Everything happens and nothing is recorded/In these rooms of the looking-glass.”

In the context of WestBund 2013, “Reflecta” seeks to demystify first of all the divine aspect of the dome roof. It has nothing to do with metaphysical tenets: it refers purely to the people’s destiny, to human history and human memory. The power of destiny and the history and memories here float around the great space, sometimes apparent, sometimes not, waiting for us to listen, observe and experience.

Eisenstein once said that old cinema sought to express a single storyline from many different angles, while new cinema presents a single perspective through multiple storylines. Listening, observation and experiencing — these three actions correspond to the three main artistic threads in the thematic exhibition: the sound, video and theater aspects of Chinese contemporary art since the new millennium. The three elements serve as contexts for each other, developing independently while converging into a unique social force that reflects the historical process and trajectory from different angles.

Listening

A century ago, the futurist artist Luigi Russolo pioneered the age of modern sound art with his Intonarumori (intoning devices). From that point on, industrial machinery and the metropolis have become significant themes of sound performances; furthermore, musical sound’s opposing force – noise – began to produce its own perceptive torrent and creative power.

However, a hundred years later, WestBund 2013 sees sound foremost as a method of testing the site. In the vast, six thousand square meters of cavernous, circular ruins, the first sound we hear is that of “silence.” “Where word breaks off no thing may be, ” and silence is not simply the absence of sound. Silence is an intrinsic part of human language and music; it is the foundation that makes all speech and sound possible. However, silence as a listening experience has been permanently lost amidst the constant background noise and clamor of the modern metropolis. The sound of the city has detached itself from its original time and space, being transmitted, replicated, echoed, and layered endlessly through modern media system. Sound no longer begins in silence nor fades into it. It can no longer return to silence, only be shifts and dispersed among other discourses and sounds.

Nevertheless, in the darkness of the dome, that long-lost silence seems to reappear. Here, silence represents the part of history that lingers in the shadows: the circulation of air, the faint rustling of litter, the whirring of machinery through time, the murmurs of workers; all these merges into the "resonance" of silence. Through this "resonance" of the ages we then hear the distant clamor of the mundane world and the agitation of the city's sounds. Every modern city is a sound theater, and in China's sound history, Shanghai is undoubtedly the most spectacular one. From the blaring of boat horns on the Huangpu River to trams, from the singing and dancing at the Paramount to the cries of peddlers in the alleyways, from Cultural Revolution-era propaganda to Shanghainese stand-up comedy ... all these varied forms come together, fragments of sound mixing with those of everyday life, creating Shanghai’s ever-present soundscape and its unique sound culture.

If we set aside for a moment the ocean of sound phenomena, can we distinguish the whispers of history and rumble of a transforming society? As an important component of the Reflecta section, the sound art exhibition curated by Dajuin Yao, titled "RPM," explores the "revolutions per minute" in the current sound reality. Revolutions happen in a snapshot: they are a reversal as well as new beginning. In an age of CDs, sound depends on the revolutions of a disc to be heard. The revolutions every minute and every instant give birth to the sound revolution, which is then put into an endless loop. This is the sound exhibition’s response to “Reflecta.” It is hoped to derive a political economy of sound from the creation and contemplation of Chinese sound art, thereby fostering a social listening experience and a society attuned to listening.

Observation

The reality on the screen is a watched reality, while the reality around us is an unseen one that surrounds us. The world presented on-screen is the “seen world,” or in other words the“visible world.” It is also the world that is “watched and used for watching .”

The audience focuses on those images that are inflated and see them as a separate world in which their moods oscillate from the peak of happiness to the trough of gloom in an instant. At the same time, the audience lives on in an everyday reality they have difficulty facing up to. The Everyday is scattered and yet endless, inscrutable, whereas the images provide a way to face the world. “Perspective can perhaps no longer represent the distance between myself and the world; it determines the position of the world with me at the center, putting the world before my eyes, making me forget the world is also behind me and that I am a part of it. The video camera also allows observation of the world from without.” These words of Stanley Cavell are right on the mark. The secret of cinema lies in its representation of a desired vision, one that is severed from our continuous experience and thus can be fully grasped. We observe the cinematic world in obedient comfort; it has long been objectified and represented by another eye external to the world, so it is a “seen world.”

It is this “seen world,” this "watched and watching world," that defines us as mere spectators and increasingly erodes our capacity as producers. This spectacle of video is precisely what the video art special exhibition Resolution Power aims to critique and resist. Curated by Guo Xiaoyan and Liu Xiao, the exhibition posits that the resolving power of video is not just about making reality clearer, but about returning that clear and definite image of reality to an indeterminate state. In the media age, we can no longer directly deal with reality itself: instead we must deal with and observe a pre-expressed, pre-packaged image of reality. The "resolution" of reality images is not just about interpretation, but more importantly, about deconstruction.

And the power of deconstruction comes from the ability to transform images into actions. The video special exhibition aims to call forth a “performative video” that does not rely on the techniques of “direct cinema” (using video to take action), but rather about making the image itself become the action.

Performative video with resolving power is not a new form of image but rather a form of video mobilization, continually reminding us of the intrinsic relationship between image and perception. Life and action are unshowable, just as the most fundamental video can only occur once – Pasolini said that a person's life is just one long take. Video as experience is continually developing and being experienced. It is isomorphic with our lives and, therefore, has the potential to continuously reconstructour relationship with reality.

It is a challenge to find moments in the current art history narrative where video becomes performative. Artist Chen Chieh-Jen once recounted an obscure moment in image history during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan (1895-1945). Japanese colonizers showed Japanese-language films as part of a propaganda drive inspiring loyalty to Emperor Hirohito. Since most Taiwanese could not understand Japanese, local interpreters, known as " Benshi (弁士)," were recruited to transmit the message of the films to their audience as they were broadcast. Many of those benshi had been members of the resistance and would often seize the opportunity to misinterpret the film subtitles into anti-Japanese propaganda instead. The resulting impression in the mind of the audience was a curious hybrid: Japanese propaganda plus speeches of defiance against the same material. The whole experience left the Taiwanese audience with a paradoxical image in their minds.

A second instance of a poignant video moment was early during the Civil War (1945-1949) in the remote area warzones of Shanxi, Hebei, Shandong, and Henan. At that time film was coming to play an ever more important role in the war effort, with visual information of the entire war zone being disseminated to every soldier and civilian through temporary exhibitions on street corners and in barracks, as well as photo albums passed around in trenches. Taking photographs was a significant event in the life of the troops. Before launching an assault, the accompanying photographers would take pictures of each member of the dare-to-die squad. It was a solemn moment in their lives – perhaps their last. The soldiers vaguely knew that due to material shortages, the cameras might not even contain film. Nevertheless, they dressed their best for the occasions, faced the lens, took their positions, and after taking the last and possibly only photo in their lives, charged into the perilous battlefield.

Those moments – whether it was the benshi used imperialization films for anti-Japanese propaganda during the Japanese occupation or the photographers in the trenches raised empty cameras to take pictures of soldiers before charging – are important moments in the history of Chinese imagery. The film where visuals and sounds were paradoxically opposed, and the filmless photography ritual before the assault, allow us to consider the essence of video from another perspective. These images, transmitted and accumulated in the minds of the people, gradually produced a liberating energy, transforming into the courage to act..

Resolution, as a performative video, does not mean only the use of video to call forth action in real life. More importantly, it calls on us to liberate ourselves from the passive position of spectators and to become producers of images once again. To do so we must reclaim our creative ability that has been wrested from our grasp. Here, “video” is a verb; it means to interact with and perceive video in the most personal way, to reflect on oneself through the process of video production, and to create new ruptures and poetics in the dialectic of life-action and personal-reflection. In the unfolding of this new poetics, images become actions, experiences are no longer ready-made, perception remains sensitive, and the world becomes vibrant once again. In this way, the performative video that resolution points the way to will not merely be “the video of producers” but also a “liberated” video.

Epilogue

What kind of era do we live in?

An era where nobody is satisfied with themselves, except in political propaganda. Therefore, The Other Bank has become an “existentialist part “of our lives. However, nowadays even dreams have become tools of ideology; even “the other bank” and utopia have become consumer products of the Society of the Spectacle. As a form of life governance, spectacle entails a segmentation and reallocation of our sensibility. It is the mechanism by which the objects we perceive/experience are “packaged.” Having these objects of our experience pre-packaged is the very core of contemporary consumer society; as one of the principles of a consumerist society, it entails the reduction of human desire and hope, and the deprivation of human imagination and potential. In the face of this I have repeatedly discussed this: in this age of spectacular capitalism, the "exploitation” of people’s labor value by the productive relationship has transformed into a bio-political deprivation of people’s ability to act.

What kind of process or Reflecta are we involved in?

What was that torrential and nameless Reflecta I felt the instant I walked into the huge cavernous space on the eve of the millennium? That Reflecta transcended any self- perception bounded by our current generation as well as the causality and descriptions that historians attempt to capture. It was an inexplicable and nameless Reflecta without a specific goal or direction – and yet it was as unstoppable as destiny.

One hundred and seventy years ago, Shanghai was opened as a treaty port and this great city began its path to modernity. In the present day when we look back on, experience and decipher the memories and past of the city, the images of the masses, the shadows of empires, the splendid spectacle of modern civilization, and the legends and dreams of the nation-state weave together in a glorious tapestry. The Shanghai of old, with its foreign settlements, the debates about East and West, colonization and de-colonization, revolution and post-revolution, social awakening and national independence, the Cultural Revolution and Reform and Opening Up – this Reflecta, entangled with the gestures and movements of countless people, the overlap of shadows and images, the reverberation of sounds and voices, and the mixture of good and bad, reflecting the struggles and quest for a better life, and the vicissitudes of that life, of the Chinese people over more than a century. Trapped in this complicated and yet majestic Reflecta, how do we deal with it? What can art do?

Finally, I remind myself once again that the age we live in is a great age. Furthermore, we are lucky to live on the cusp of a new age. Although that age has not yet arrived, and although it is no more than a temporary image in a great Reflecta and whose meaning will be continually rewritten and interpreted by history, the historical subjects within this Reflecta are unafraid to become like the caged beasts in Rilke's Panther:

As he paces in cramped circles, over and over,

the movement of his powerful soft strides

is like a ritual dance around a center

in which a mighty will stands paralyzed.

Translated by Steven HUANG, George Flemming