2013

This essay is an extension and further development of a paper I delivered at the academic symposium held during the “Hanart 100: Idiosyncrasies” exhibition at the Hong Kong Arts Centre on 16 January 2014. It focuses on the theoretical approach and process of the research team of graduate students from the Institute of Contemporary Art and Social Thoughts of the China Academy of Art, assisting with the curation of the exhibition. The team comprised Liu Tian, Zhang Yang, Liu Yihong, Zhang Wei, Wang Yan, Nicoletta Jordanidis, Lu Ruiyang, Zhang Cheng, Lü Hao, Wei Shan, Zou Shu, Li Qiao and Zhu Xian.

The Nameless State

In January 2014, visitors entering the first gallery of the “Hanart 100: Idiosyncrasies” exhibition at the Hong Kong Arts Centre were confronted by the presence of three twentieth-century Chinese “art things.”

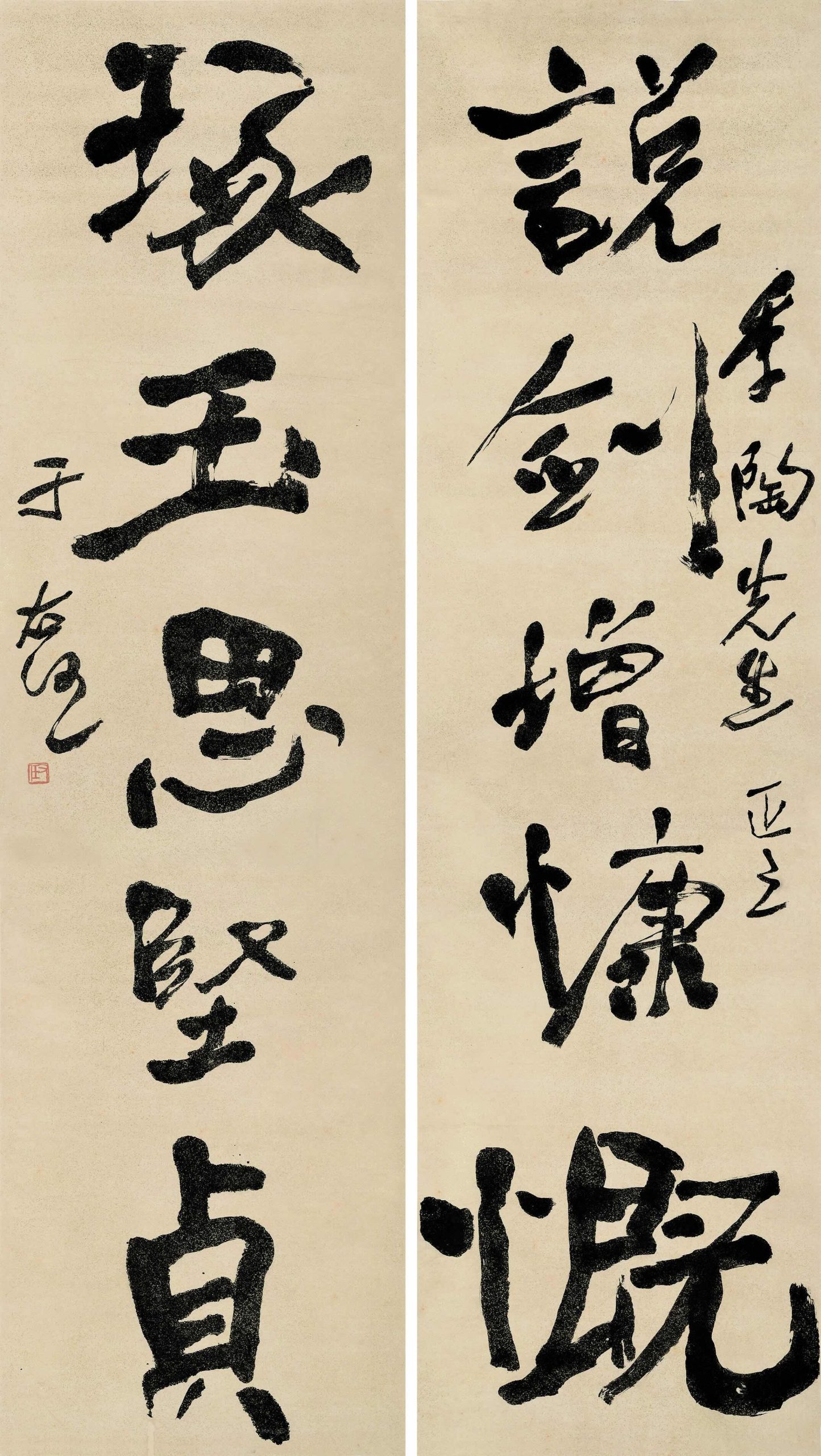

The first was a calligraphic scroll by Yu Youren (1879–1964), a grand patriarch of the Republican era (1912–1949), on which he had written the following aphorism:

When talking of swords,

be more broadminded and tolerant;

When carving jade,

think of virtue and constancy.

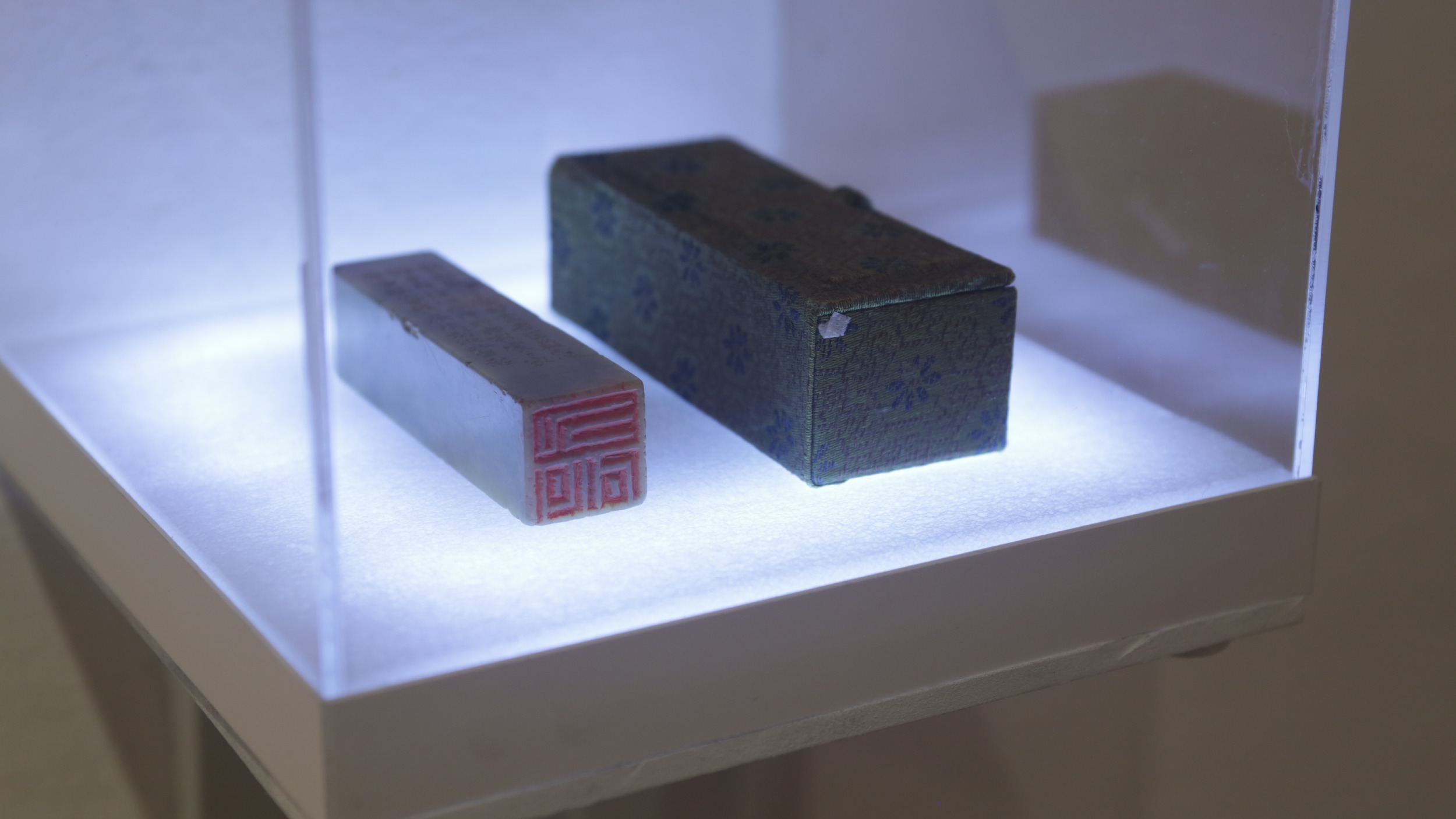

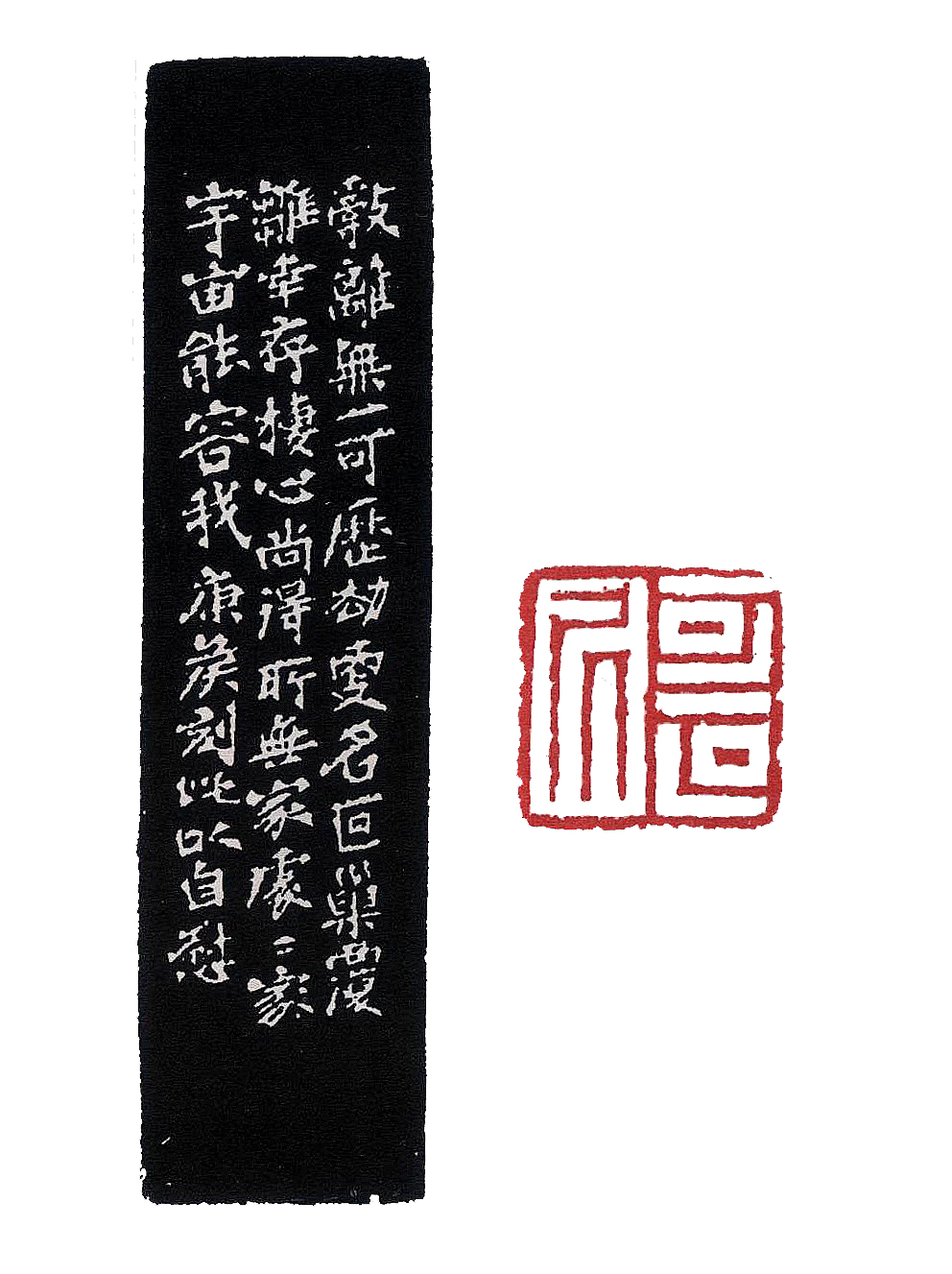

The second was a stone calligrapher's seal carved in the 1960s by Feng Kanghou (1901–1983), bearing his studio name “Acceptable Unacceptable Dwelling,” and inscribed on the side with the following poem:

There is nothing good to be said of chaos and dispersion

After all these tribulations I have changed [my abode's] name to Unacceptable

The chick is lucky to survive the overturned nest

And find a dwelling for his heart

For the homeless one, home is everywhere

The Universe holds a place for me.

Carved to console myself, Feng Kanghou.

The third was a set of drawings dating to the early 1950s, comprising design drafts for the historical friezes on the Monument to the People's Heroes in Tiananmen Square (figs 1-3).

Encapsulating the pioneering spirit of the New China, the passion and breadth of vision of the Republican period, and the lonely soliloquy of a sojourner in exile, these three art things collectively introduced both the panoramic and microscopic view of China's art and history of the past century which the “Hanart 100” project seeks to explore (fig. 4). While the calligraphy scroll and the seal carving were created by noted artists, the set of design drawings for the Monument to the People's Heroes is essentially a project with no definite attribution. Yet through its very anonymity it becomes a tangible part of an organic and systematic process of naming—the search for a name, as well as a form, for a country that was as yet nameless and amorphous.

Some 2,200 years ago, when the Han dynasty was first established, the state chancellor Xiao He was placed in charge of constructing the Weiyang Palace. In the process, he gave the following advice to the first Han emperor, Liu Bang (Emperor Gaozu, 256–195 BCE): “If [the palace] is not splendid and magnificent, it will not inspire awe, and if it does not inspire awe, future generations may be tempted to alter it.”

In this embryonic phase of establishing a system of governance, an earnest process began of gathering together a variety of blueprints and drawing elements from them to produce a singular template, one that would solidify in physical form both the philosophy and history of the state, while at the same time signaling the new spirit and future path of the nation. Thus, the dozens of draft drawings solicited from all over China for the design competition of the Monument to the People's Heroes represent a valiant effort of naming at a time when the state ideology had not yet coalesced into a final form. In these drawings, all manner of design elements were thrown into the mix, including double-eaved palace roofs, steeples, jade cong tubes, statues, calligraphy, the five stars motif, military medals, flags, etc. —all part of a “symbolic operation” in which “the word was made flesh.” The ultimate goal was to come up with a satisfactory answer to the question of how to accurately and fully represent the character of the newborn nation.

In ancient China, outstanding deeds and memorable achievements were immortalized by being inscribed on stone stelae and bronze ritual vessels, but these were not “monuments” per se. The concept of raising a monument in an urban public square only became institutionalized in China after the country underwent modernization. The confluence of this modern concept with the tradition of the stone stele and the ritual vessel produced, via historical accumulation, a unique cultural genome that has a direct correspondence with the basic starting point of the “Hanart 100” project: the framework of three artworlds coexisting in China today—the globalized artworld; the traditional Chinese literati artworld; and the Socialist artworld.

fig. 4 Panoramic view of “Hanart 100: Idiosyncrasies” exhibition, Hong Kong Arts Centre, January 2014

The Nameless Aggregate

In November 2013, when we were in the initial stages of planning the “Hanart 100” exhibition, a member of our team asked, “In curating this show are we going to follow the theoretical path of the three artworlds?” I replied that the concept of the three artworlds should be viewed as the “theoretical object” of our curatorial work. In other words, we should use the curatorial process as a methodology to tease out from within the three artworlds framework different trajectories of interpretation and understanding, and possibly an even more progressive level of theoretical reflection.

Thus our first task was to gain perceptions of and perspectives on the 100 “art things” in the exhibition. As we pored over the works, we discovered that each one of them spanned at least two of the three worlds. While the three worlds could be considered as the reverberations in art of the dominant paradigms of three different political ideologies, conversely, they also could be seen as political constructions created by three different modes of artistic awareness and technical skill. But this kind of unilateral, cause-and-effect interpretation is an oversimplification of the model, whose actual complexity lies in the way that it is continuous, interactive, conflicting and infectious over the course of several historical periods.

In fact, an extremely important point to note is that the three artworlds framework is not overly focused on the noumenon of “art” (that is to say, its focal point is not the critical evaluation of the quality of an artwork or an artist), but rather on the “three artworlds” as three different kinds of “production systems,” or end products of three kinds of historical processes; and then takes these three models as the phenomena of description and analysis—this is the framework's most fundamental and forceful raison d'être. Yet to a certain degree, our curatorial work began from outside this theoretical framework.

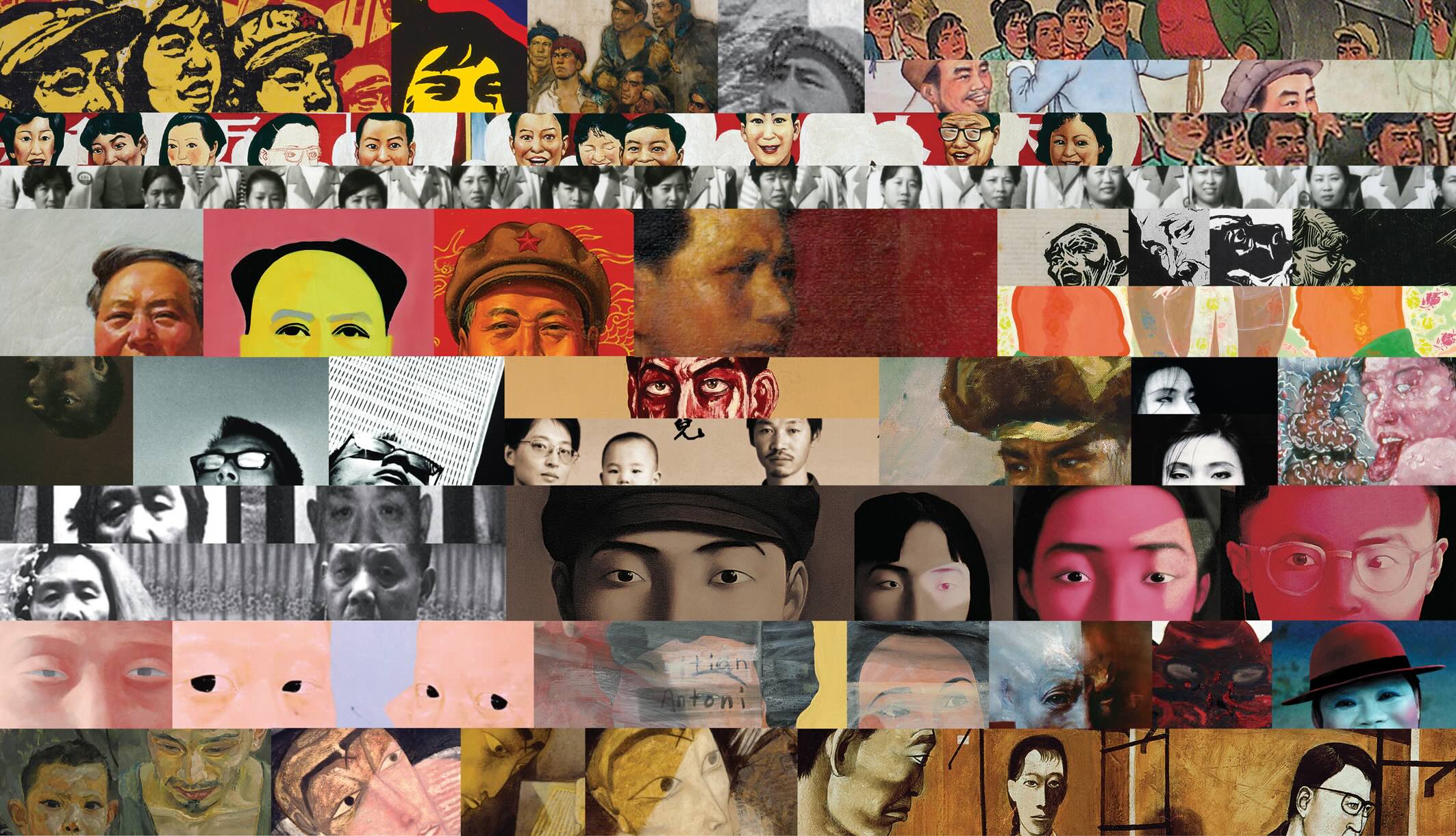

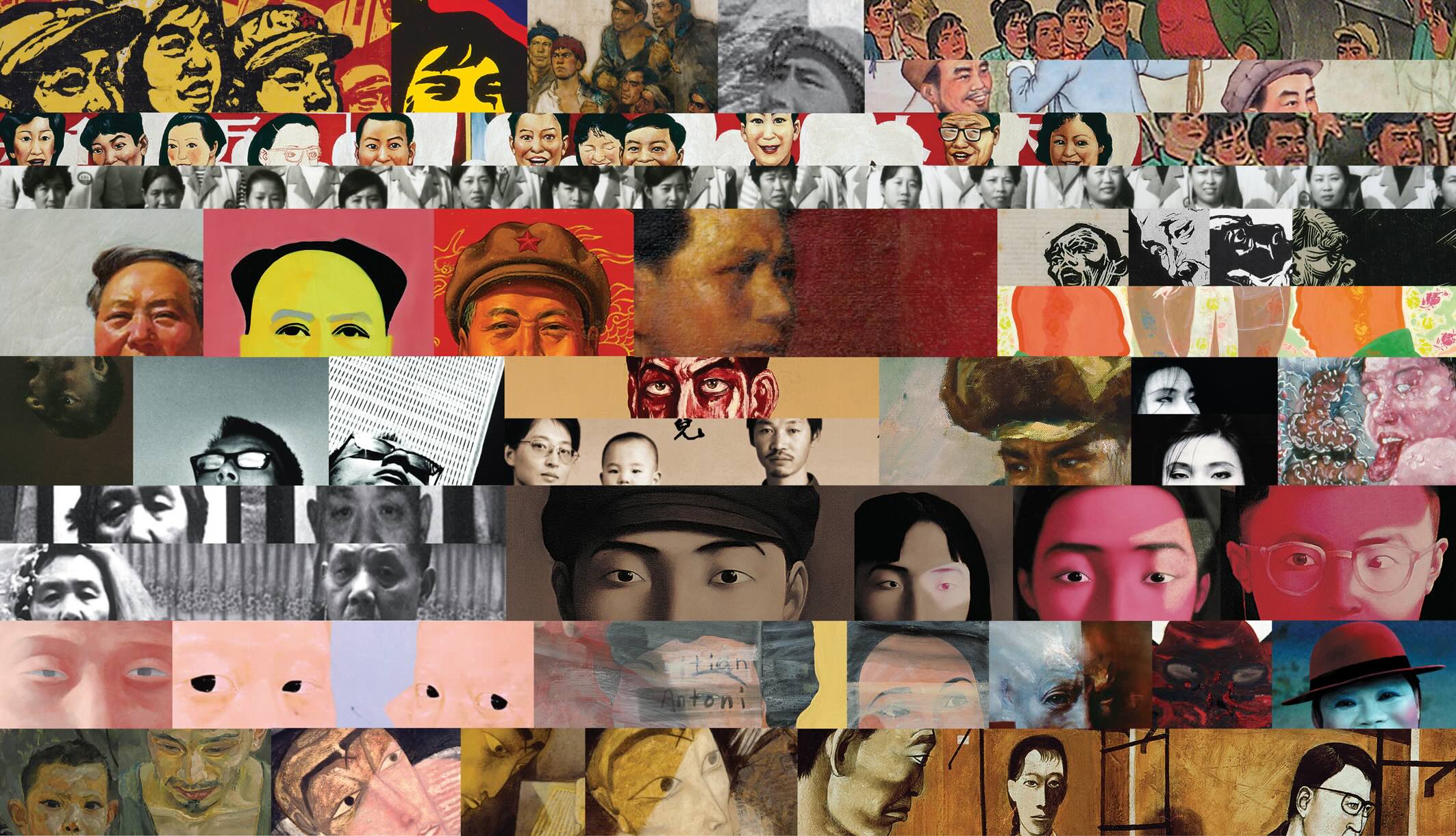

Thus, instead of dividing the 100 works into different “species,” we put them into different “sets,” physically separating them into the following thematic groups: Overture; The Masses; The Multitude; The People; The Word; Mao; Mountains and Rivers; Home Land; The Body; and The Net. Each one of these thematic headings comprises the smallest possible unit (the Chinese character) that contains within itself multiple implications, and that at the same time points to a vast and complex network of Chinese language concepts, both inseparable and antagonistic: The People are confronted with their external enemies; The Masses commune with the Party leadership; the emergence of a nation state is contrasted with the loss of a Home Land (fig. 5). “The Body” refers back to a poem by Song-dynasty literatus Su Dongpo, in which the poet writes: “I always regret that this body does not belong to me.” It also references the “lofty, noble, and perfect” bodies of the heroes of the Cultural Revolution operas, who sacrificed themselves to the revolutionary cause, as well as the body of the “everyman,” and the human figure that serves as a subject in traditional Western art. This is the same body that is at once the contested subject of multiple gender movements; the conceptual sarira, or “human pearl” relics of the Buddha; and the metaphysical “thing (body) in itself” (fig. 6). There was one “super-being” who was able to interact with nearly all the other communities, yet could not be integrated into any one of them: Mao (fig. 7).

In this sense, what took place in the exhibition space was not a permanent consignment of works to specific classifications, but rather a temporary arrangement; not a set of Aristotelian “genus-differentia” definitions, but rather an intra-communal “dialogue” in the sets, a series of chance encounters, examples of intertextuality, compounding, radiation, transference, and contrariety. All of this in a sense echoes the line in calligrapher Wang Xizhi's (303–361) famed scroll Orchid Pavilion Preface, in which he writes: “[Some] found satisfaction in a closeted conversation with a friend, but others, led by their inclinations, abandoned themselves without constraint to diverse interests and pursuits...” In this transient gathering or “get-together,” the works of art, again quoting Wang Xizhi, “draw upon their inner resources...the cause of their melancholy is the same as my own...”

Of course the works that faced us were only silent objects and images. And so we imagined ourselves in the role of archeologists of the future, excavating a major find of 100 specimens. Like the modern explorers who discovered the pyramids for the first time, we asked the questions: How to begin to understand them? What is it that they most want to be discovered? What aspects are of the greatest value? Even though each of the artworks was famous to some degree, as we planned the exhibition we viewed both the works and their creators as “anonymous” and “nameless,” sans titre. Our purpose was to regard them as layers of interface—as historical wounds or scars—with all the chaotic momentum of the past collapsed into them, awaiting another summoning.

fig. 5 Conceptual diagram used in planning the “Hanart 100: Idiosyncrasies” exhibition, showing The Masses, The Multitudes, The People, Home, Country (Land), The Party

fig. 6 Exhibition view of “The Body” set

fig. 7 Exhibition view of the “Mao” set

[1] See Giorgio Agamben, “Aby Warburg and the Nameless Science,” in Potentialities, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999).

The Nameless Study

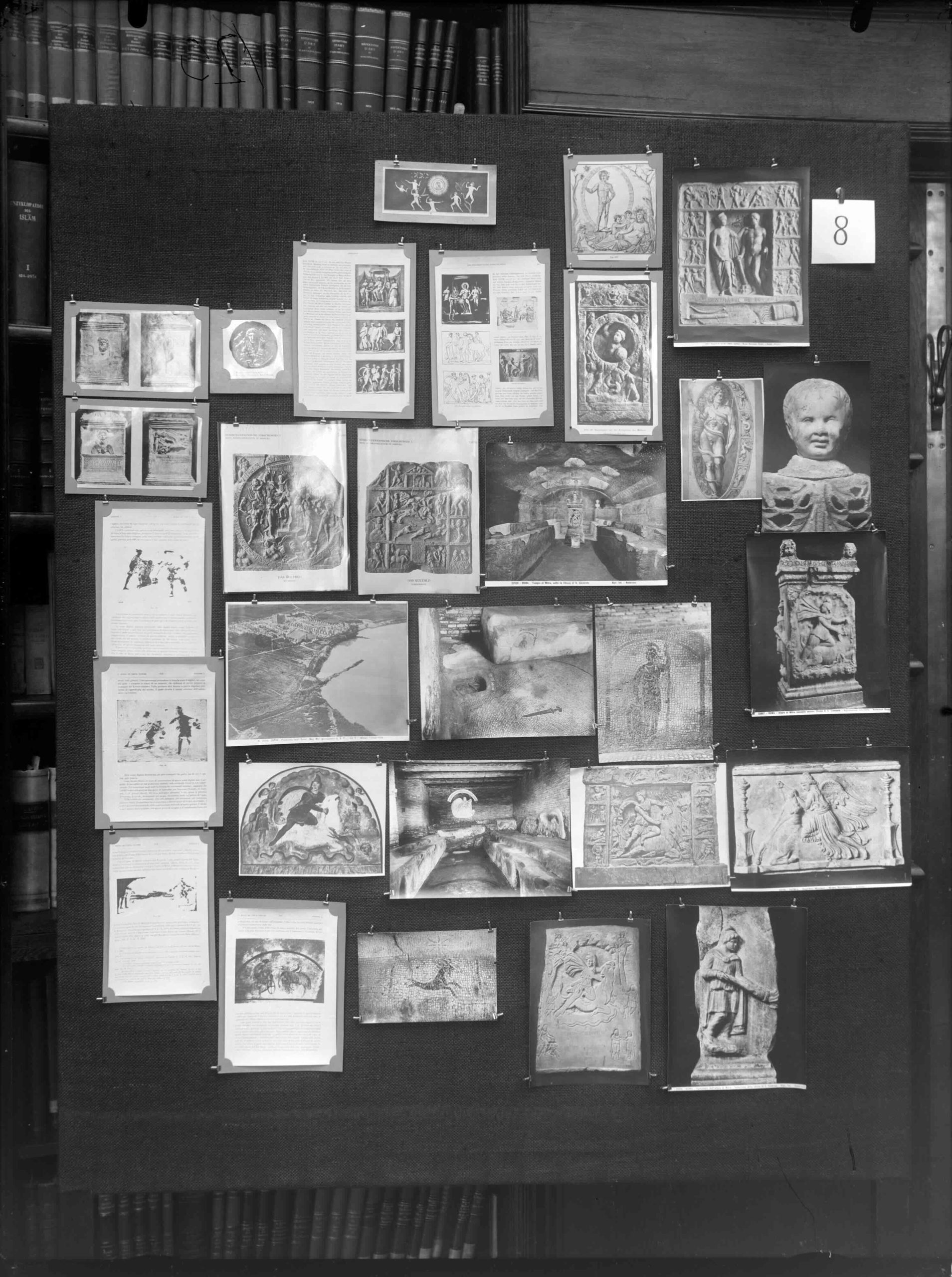

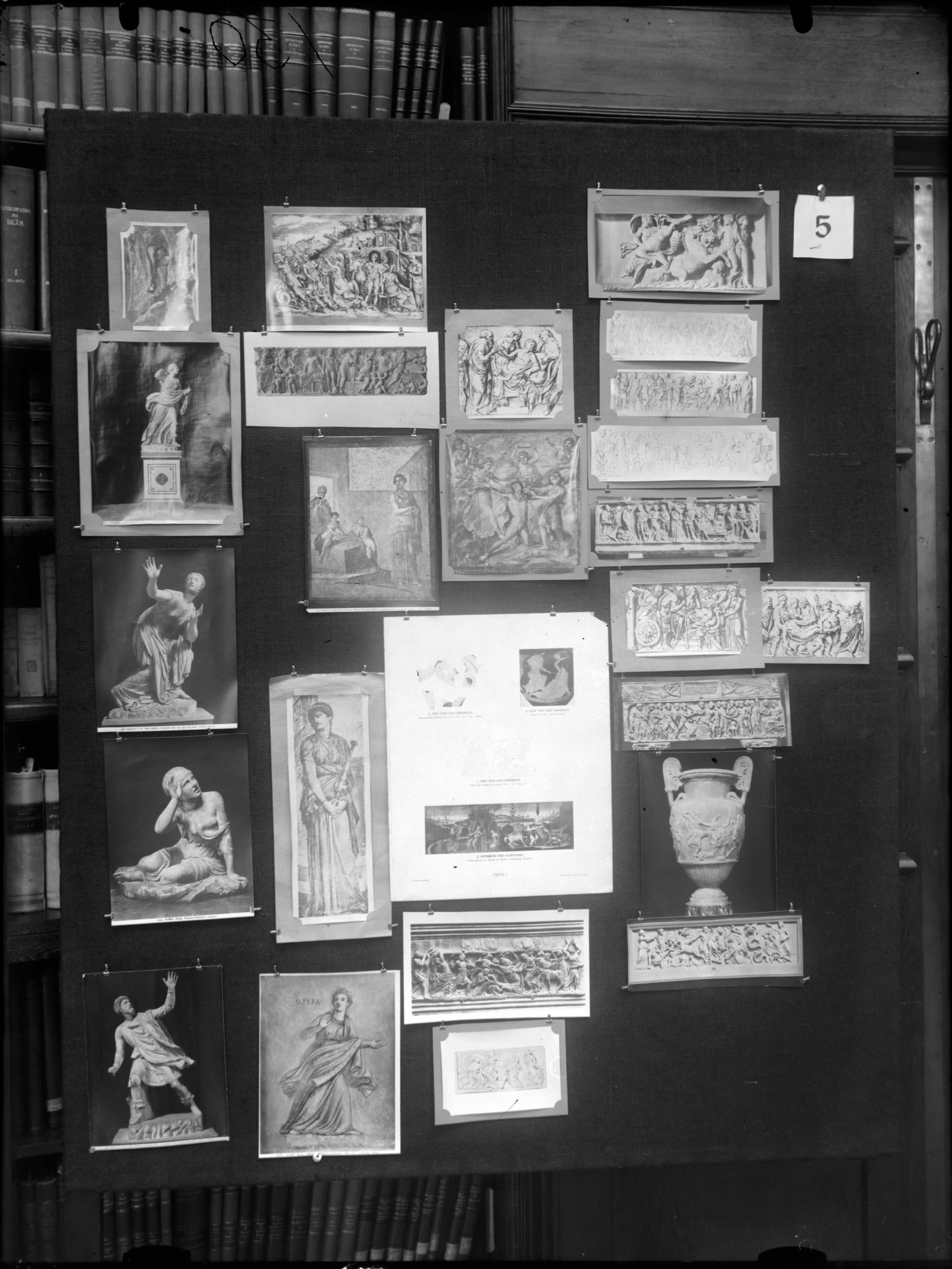

During our planning process, the Mnemosyne Atlas created by the German cultural theorist Aby Warburg (1866–1929) was a major source of inspiration (fig. 8). Warburg's use of the concept of the atlas was closely related to our approach: akin to the drawing of a map, or even more, to the piecing together of a jigsaw puzzle. Each minute detail, and the gaps in between, came together to construct a vast panorama, making visible something that could not normally be grasped by the human eye, or rendered on a conventional scale. Interestingly, the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben has described Warburg's Atlas as “a scholarly discipline without a name,” and “a nameless science.”[1] As Agamben sees it, Warburg's goal in creating his own school of thought, which only after his death came to be known as “iconology” or “iconography” (although that particular definition may not be entirely accurate) was to resolve the opposition between history and anthropology, and to give form to questions that are both historical and theoretical, because images strictly speaking are neither conscious nor unconscious. Several key concepts closely related to the ideas raised in “Aby Warburg and the Nameless Science” were a constant part of our discussion: for example, the idea of yitu, which in Chinese means both “intent” and “image”—the hidden intention in a painting or an object (this ambiguous term combines the notions of “idea” or mental activity and external “form” ); and qingnian (roughly, emotion-remembrance), which came directly from Warburg's idea of “pathos,” or the German Pathosformeln (literally “emotional formulas,” but in Warburg's usage an emotionally charged visual trope). But here we should not forget that the concept of pathos comes from Aristotle's Rhetoric, specifically Section 2 of Chapter One, in which Aristotle cites three different means of proof or persuasion: logos, ethos and pathos. Pathos also lies in the interaction of the two elements of emotion and remembrance contained in the Chinese term qingnian. Finally, we considered the concepts of jiegou “structure,” zitai “attitude,” and in the historical context, qianneng “hidden potential” and shineng “active potential.” To some extent, our curatorial practice followed the same line of thought, methodology and ultimate mission as did Warburg in his day, going beyond iconology.

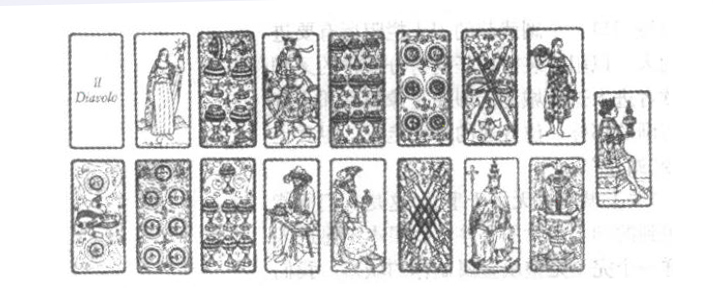

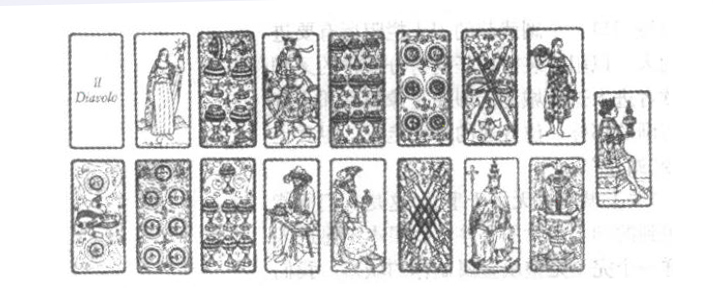

As we neared the exhibition's opening day, I frequently recalled Italo Calvino's novel, The Castle of Crossed Destinies. The story revolves around a group of strangers who find themselves seeking refuge together in a castle, and who all mysteriously lose their ability to speak. They then use a set of Tarot cards, arranging them in different sequences, to silently tell their own stories (figs 9a–9b). As the different characters in the novel use the cards—or rather the images on the cards—they are demonstrating semiotic theory: How the same sign appearing in a different context can produce a different set of implications, and contain an infinite number of random possibilities not limited by the specific images that appear in the pictures. But their use of the Tarot cards not only constitutes a kind of literary card game, wherein a set of images are used to produce a variety of different scenarios; more than this, they were echoing the original function of the Tarot cards—to divine the future. The Tarot employs a limited system to address limitless outcomes; it relies on the mystery of its limitations to control greater mysteries.

In the same way that the Tarot cards were spread out in Calvino's silent castle, artworks and the spaces that they inhabit also take part in a kind of silent dialogue. Bringing the special configuration of the Hong Kong Art Centre's space into our thinking, we used the space to help us generate and invent both antithetical and referential relationships among the diverse artworks. (A straightforward example is the way Geng Jianyi's Misprinted Books, which, with its over-printed texts, directly faces Fu Lin's woodcut propaganda poster Mao Zedong's Thought is Our Life Blood. This poster features multiple copies of “the one and only book” —a book that has been reprinted countless times [fig. 10].) The reflections and refractions among the different walls and surfaces, the linkages between the upper and lower floors, and the polygonal structure of the Hong Kong Arts Centre's overall layout all became part of our conceptual process (fig. 11). In particular, we treated the spiral nature of the galleries' interior architecture as a single surface, or “great wall,” that wound its way around the exhibition space, and which also allowed us to plan the final destination point—a special section exploring historical roots and dynamics. (Marx said that history rises in a spiral, but in fact in our case it descended and terminated in a spiral): this was the thematic set/section we called “The Net.” Four artworks/art things that most powerfully illustrated the most tumultuous, benighted, chaotic and insane years of the twentieth century—The Book of Yinfu, A Madman's Diary, Lingchi: Echoes of a Historical Photograph, and Red Flag Canal—were placed beneath the dragnet of Taigong Fishing for Those Willing to be Hooked (fig. 12). Surrounding all of this was the “sound wave wall,” a chronology of historical events in Mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong that took place over the past century: each event, and each work of art, was interpreted as an individual sound source, with their varying levels of strength or weakness acting like the varying pitch of a sound wave, producing echoes that continue to reverberate until the present day (fig. 13).

Within this “sound wave wall,” or “historical spectral line,” are manifested the historical symptoms of what May Bo Ching calls “structural amnesia.”8 The different events and works of art seem to be arranged in a simple juxtaposition, and history emerges as a prefabricated “readymade” with all the events and art things in superficial proximity, with no apparent connection to each other. This echoes Professor Johan Hartle's discussion concerning Global Art, as raised by thinkers such as Hans Belting, and the key concept of “peaceful coexistence.” However, by taking this concept as our starting point, we followed a thread of association back to the 1950s, when China put forward “the five principles of peaceful coexistence” as proposed by Zhou Enlai (mutual respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty; non-aggression; non-interference in each other's internal affairs; equality and cooperation; peaceful co-existence). We then counterpoised these “five principles” with other resonant instances of political theorizing: The Cold War theory of the “three worlds” put forth by Mao Zedong in the 1970s, the Clinton administration's promotion of globalization in the 1990s, and the idea of the “small country with few people” raised in the ancient Daoist text Laozi (Chapter 80), “Where people take pleasure in their food, wear fine clothing, live in safety, and are happy in their ways. Living within sight of their neighbors, they hear their dogs barking and cocks crowing, yet they never leave their hometown, and die there peacefully in old age.” Considering these diverse theories together, a pattern began to emerge, bringing with it the possibility of arriving at other, more subtle and more complex levels of perception. This was just the kind of subtle, complex understanding that we were seeking through our reading of these historical events and art things—the “echoes from the three artworlds.”

Although the exhibition has closed, our work on the “sound wave wall” of history continues. The questions we posed concerning the relationship between art and politics ultimately turned the entire exhibition inside out, revealing the true substance of the task that lay before us. In Warburg's view, artworks are like Leiden jars in which temporal energy is accumulated and preserved. Yet in the end, the ultimate purpose of Warburg's library was to lead beyond art history to a broader and more integrated form of learning. It is only by approaching the abyss that we can shed light on the fracture that is hidden within ourselves.

fig. 9 Narrative arrangement of Tarot cards, from Italo Calvino's novel The Castle of Crossed Destinies

[1] The full text of Zhou's inscription reads: “Eternal glory to the heroes of the people who laid down their lives in the People's War of Liberation and the People's Revolution in the past three years! Eternal glory to the heroes of the people who laid down their lives in the People's War of Liberation and the People's Revolution in the past thirty years! Eternal glory to the heroes of the people who from 1840 laid down their lives in the many struggles against domestic and foreign enemies and for national independence and the freedom and well-being of the people! September 30, 1949, marking the first plenary session of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference.”

The Nameless People

That great “national treasure,” the Monument to the People's Heroes in Tiananmen Square, bears on the front side an inscription written in the calligraphy of Mao Zedong: “Eternal glory to the people's heroes,” and on the reverse side, an inscription in the hand of Zhou Enlai, in which there are multiple iterations of the phrase “eternal glory to the heroes of the people who laid down their lives in the people's war of liberation and the people's revolution.”[1] Who, in fact, are the “people's heroes?” And which “people” aren't “heroes?” Long ago, the Chinese compound noun renmin (人民) had already evolved into a single concept. Originally, ren 人 meant the rulers, the aristocracy, and min 民 meant the ruled, those who were enslaved. As we “trace” the origins of the inscriptions on the monument, the question arises of when the “people's heroes” made their first appearance. This also leads to another question: Are “the people” (min) who appear in “The People's Republic of China” (Zhonghua renmin gongheguo), the same as “the people” (min) who appear in the “Republic of China” (Zhonghua minguo)—do they have the same meaning? Has there been some migration we are not aware of? We can also trace our way back to Sun Yat-sen's “Three Principles of the People” (Sanmin zhuyi): Nationalism (minzu, lit. the nation of the people), governance by the people (minquan, lit. power of the people), and the people's livelihood (minsheng, lit. the life of the people). Are Sun Yat-sen's three min also part of one and the same entity?

Having made three thematic groupings under the headings of the Chinese terms qun 群 (The Masses); zhong 众 (The Multitude); and min 民 (The People), we began a process of juxtaposing Chinese linguistic sources, Western language translations, and contemporary usages, together with different perceptions or interpretations of the artworks, as a means of more deeply penetrating these concepts that are at once both familiar and problematic, as well as the intersections and subtleties that existed among them.

The character 群 (the masses ) is composed of two elements: 君 (jun) meaning both “gentleman-scholar” and “sovereign” and 羊 (yang) meaning sheep. In the classical poetry anthology, The Book of Songs, the character 群 is used in the following line: “Who says the shepherd has no sheep? He has a flock (群) of 300.” 群 can also be written as 羣, which shows the gentleman/sovereign resting on top of a sheep. (It is most intriguing that the Chinese words for some of the finest ethical values have a sheep element in them: 美 beauty, 善 goodness, 義 righteousness. “For he is our God, and we are the people of his pasture, and the sheep of his hand.” [Psalms: 95, 6–7]). The Christian missionaries called themselves “pastors.” “The masses” represent a quantity that increases at random, lacking in structure and interconnectedness, and only capable of exhibiting anarchic “Brownian motion;” thus the “sovereign” is in charge in name alone. In Gustave Le Bon's The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1896), the early French sociologist concluded that the “crowd” is controlled by unconscious forces. But one of the virtues of the crowd, or the masses, lies in the peculiar state of “isolation.” In the “Weiling gong” section of the Confucian Analects, the Master says: “The superior man is dignified, but does not wrangle. He is sociable, but not a partisan.” Even though there exists a constructive organic association between the individual and the masses, this associative condition does not sacrifice the “public.” Today, of course, the “parti-”(党) in “partisan” refers to the “Party.”

The late Qing-period scholar Yan Fu translated the title of Herbert Spencer's The Study of Sociology as “The Study of the Masses” (Qunxue yiyan), and John Stewart Mill's On Liberty as, literally, “Concerning the Boundary between the Rights of the Masses and the Self” (Qun ji quan jie lun). He rendered Spencer's concept of “the society and the individual” as, literally, “the national masses and the small self,” which seems like a rather profound interpretation combining the traditional and present-day Chinese understanding of the notion of “the masses,” and even anticipates the emergence of “Socialism” in China.

In the “Zhouyu” (“Discourses of Zhou”) section of the Han-dynasty text Guoyu (Discourses of the States, 5th–4th c. BCE) it is written that “Three animal forms comprise the character 群 (qun), and three human figures comprise the character 众 (zhong).” There is an evolutionary distinction of status between these two characters. The traditional form of the character for multitude, 眾 (zhong), evolved into its simplified form 众, which is made up of three “persons” with one person (人) emerging as dominant and rising above the other two; herein lies the birth of management structures and the class system. As for min 民 (the people): Well, to begin with, they're poor, and they are also min 憫 “pitiable,” because they are the workers. According to the earliest Chinese dictionary, the Han-dynasty compendium Shuowen jiezi, min 民 means “a multitude of sprouts,” thus something that requires nourishment and cultivation. It awaits genesis, and thus the Song-dynasty scholar Zhang Zai (1020–1077) wrote, “I will set my mind on serving Heaven and Earth; I will devote myself to nourishing the people.”

If the exhibition space of “Hanart 100: Idiosyncrasies” can be said to have featured a particular dialectic, tête-à-tête, or staring match, it was the one taking place between The People and Mao (as revolutionary, leader and deity; and his legacy, including the repercussions and counter-accusations)(fig. 14). On one wall, draped in a bathrobe, the Great Leader waves at the people (Tang Xiaohe's Strive Forward in Wind and Tides) while on another, a young man extends his arm in a similar fashion, although he is in fact gesturing towards an artificial “dawn” painted on a backdrop in a photography studio (Wang Xingwei's Dawn). A question arises here: Could it be that the revolution that blazed so fiercely was nothing but an empty dream, or is it rather that present-day reality is simply fraught with wishful thinking, as we look towards a false dawn (or perhaps more precisely the promise of the past) to escape from the worries and anxieties of the present?

Tseng Kwong-Chi pays a visit to the quartet of American presidents carved on the face of Mt. Rushmore, who gaze across at the Chinese leaders depicted in Liu Dahong's Sacrificial Altar. Let us consider the various mechanisms behind “The People”—serve the people, set up the people as masters of the country, stand on the side of the people; as well as the related manipulations of “The People”—arouse them, unite them, rely on them, help them, know them, protect them, educate them, raise them up, praise them, sympathize with them; and then the means of defining the opposition—separate from them, oppose them, harm them. If we then view these mechanisms and manipulations from a framework comprised of the three famous phrases from Abraham Lincoln's “Gettysburg Address”—“of the people, by the people, for the people”—we find that they fail to jibe with this framework, they are not identical to it; even as they appear to be the same, what it is about them that is so fundamentally different? The highly aroused “millions of workers and peasants” in Fang Zengxian's oil painting make eye contact with the hooligans (mang) of Fang Lijun's Cynical Realist painting (fig. 15). (It is interesting here to note that the character for mang, 氓, is composed of two elements: 亡 wang “lost” and 民 min, “the people”). Placed before the monumental triptych of Fang Zengxian, Liu Dahong and Tang Xiaohe—a kind of sacrificial altar to Mao—is Zhao Yannian's woodblock print of Ah Q, a tragic and pathetic character created by Lu Xun (fig. 16). Dragged through the mud and nearly crushed in the baptism of the revolutionary period, the pre- revolutionary Ah Q emerges as a new kind of hardened hooligan (mang) in the manner of Fang Lijun. Such hooligans or vagrants begin as “common people” (min), but due to harsh physical realties and psychological pressures, they are forced to the sidelines, and become rootless “hooligans,” “the lost.” This almost seems like a kind of biological evolution completed through social revolution.

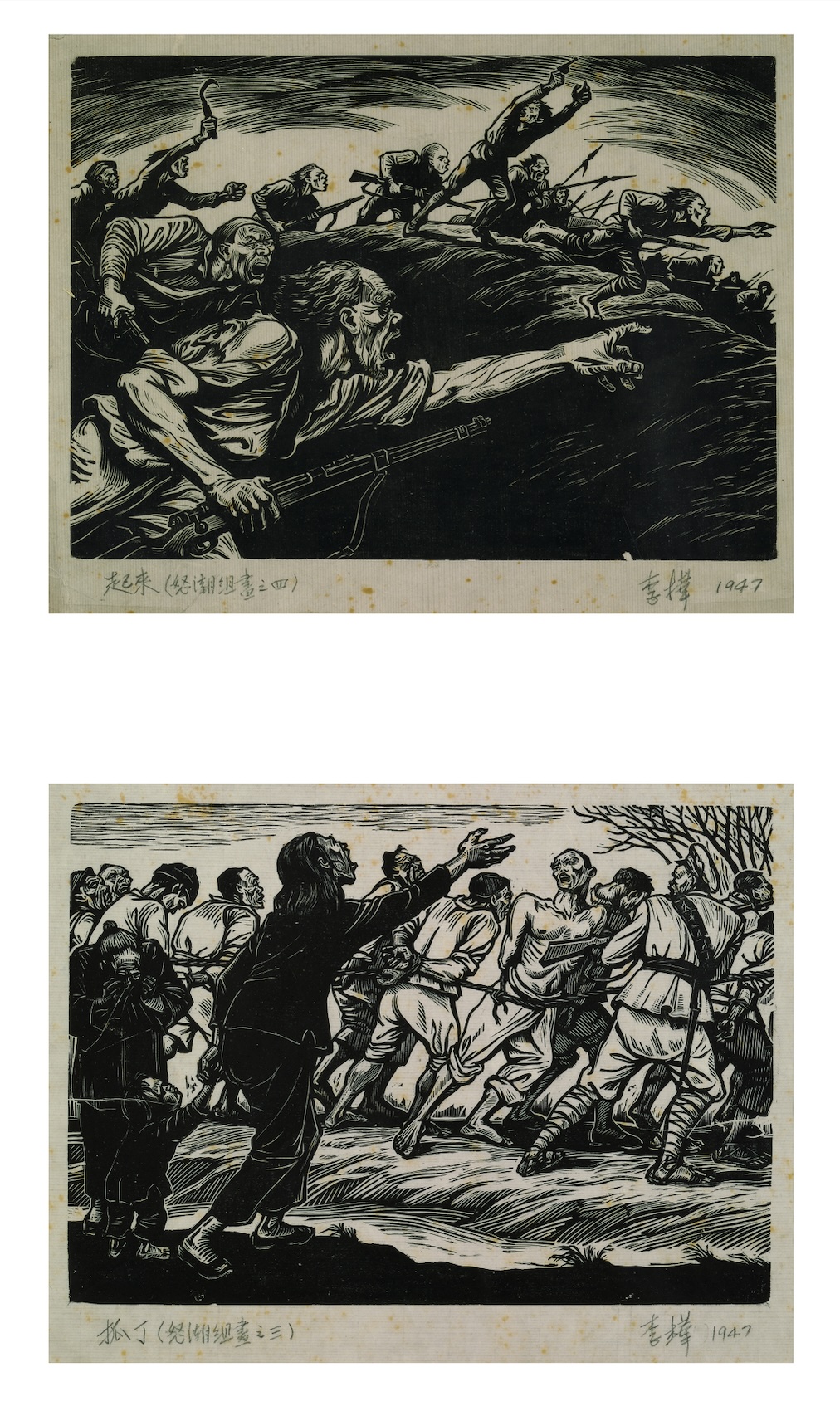

Let's turn our attention to a group of completely unrelated artworks: Press Gang of Able-Bodied Men and Rise Up from Li Hua's Raging Tide series; Zhuang Hui's photograph, A Memorial Group Photo of the Entire Crew of the Road Greening Administrative Station in Anyang, Henan Province, 13th October 1997; the anonymous artist's Huge Practice on Socialism; and Zheng Guogu's Life and Fantasies of Youth from Yangjiang (figs 17–20): when brought together into one set these disparate works trace the pictorial evolution of the collective/community over the course of the past century in China; the “hundred names,” or common people, move from enslavement and oppression to “Wherever there is oppression there is resistance!” (Engels, Mao); to the collectivized “great masses;” to “the people” who were to completely transform the world; and finally, to the “great multitudes” who live only for consumption and entertainment.

fig. 14 Exhibition view: “The People” set facing the “Mao” set.

fig. 15 Exhibition view: “The People” set facing the “Mao” set: Fang Zengxian's Arouse Millions of Workers and Peasants (1968), Fang Lijun's Series II, No.1 (1991–1992), Liu Dahong's Sacrificial Altar, Tseng Kwong-Chi's Mount Rushmore (1986), Tang Xiaohe's Strive Forward in Wind and Tides (1971), Wang Xingwei's Dawn (1994).

fig. 16 Exhibition view: “Ah Q” at the feet of the “Mao” set.

At the same time there is a visual dialogue taking place between min 民 “the people” and zhong 众 “the multitude.” The oracle bone character for min shows an awl piercing an eye ①. Perhaps that injured eye belongs to a slave, despite the fact that the slaves could and did rebel against their masters. “The people do not fear death; thus it is useless to threaten them with death.” (Laozi). The modern scholar Guo Moruo believed that min 民 “the people” evolved from the character 盲 mang, “blind,” and thus it was necessary to “enlighten the minds of the people,” to awaken them and enable them to see the light of the truth and the future. The earliest form of the character 众 “the multitude” is ②, three peasants toiling under the noonday sun, which evolved into ③, wherein the sun has become an all-seeing, all-knowing eye, perhaps that of “Big Brother,” and the overall image is that of a ruler overseeing his underlings (a situation that gradually evolved into the notion that “the masses have sharp eyes” ).

In a and b we have two eyes, seeing eye-to-eye, silently glowering at each other. One characteristic shared by the etymologies of the three characters for “the masses,” “the multitudes” and “the people,” is that in each case, the principal subject is under observation by an external force. There is a “superior” who “oversees” what is taking place below. In these situations, everybody is looking over his shoulder, everyone is visible to everyone else. At the same time, the images will only be seen through the distant view, so they are truncated and cannot be named.

The objects remain together; the people have scattered. All the artists have departed, and their artworks hold their breaths. An exhibition is a one-time gathering. This assembly of 100 art things—or in fact, any art exhibition (regardless of which art world it represents), like every CMG New Year's Gala (where several different worlds gather to be entertained at the same time)—can be seen as a form of popular “folk art.” What does “folk” mean? Whether it is the globalized contemporary art world, the traditional art world of the literati or the socialist art world, it seems that all have their roots in the “folk.” Is “folk” a fourth dimension, lying outside the realm of the three artworlds? This dimension is not an independent world of its own, functioning on the same plane as the other three worlds; it is more like the “earth” from which the three artworlds draw to build their constructs, and the common soil which they all share. Does “folk” have an antonym, an opposite? Perhaps the “three artworlds” fulfill that role. “Folk” stands apart from officialdom, government, and authority; “folk” presents a challenge to what is international, fashionable, and new wave; and “folk” is generally incompatible with refined taste, scholarly pretensions, and intellectualism...The common soil of this life-giving, primal wilderness, is saturated with the tensions of self-contradiction. Confucius said, describing the situation in his own age, “When the rites are no longer practiced [in the court], seek [the truth, a better life] in the wilderness.” For us, this may be both our place of origin, and our final destination.

One by one, we have assigned names to the nameless stars and planets, and created constellations in the emptiness. This nameless aggregate of The Masses, The Multitude and The People have left behind their long, slow, meaningful glances, and their gaze seeks to penetrate through the mists of time (fig. 21). The poet Bei Dao (a contributor of one of the Hanart 100 “art things” ), wrote in his poem, The Answer,

A new conjunction and glimmering stars

Adorn the unobstructed sky now;

They are the pictographs from five thousand years. They are the watchful eyes of future generations.

①②③

fig. 21 Composite image of gazing eyes

Translation by Don J. Cohn and Valerie C. Doran

This essay is an extension and further development of a paper I delivered at the academic symposium held during the “Hanart 100: Idiosyncrasies” exhibition at the Hong Kong Arts Centre on 16 January 2014. It focuses on the theoretical approach and process of the research team of graduate students from the Institute of Contemporary Art and Social Thoughts of the China Academy of Art, assisting with the curation of the exhibition. The team comprised Liu Tian, Zhang Yang, Liu Yihong, Zhang Wei, Wang Yan, Nicoletta Jordanidis, Lu Ruiyang, Zhang Cheng, Lü Hao, Wei Shan, Zou Shu, Li Qiao and Zhu Xian.

The Nameless State

In January 2014, visitors entering the first gallery of the “Hanart 100: Idiosyncrasies” exhibition at the Hong Kong Arts Centre were confronted by the presence of three twentieth-century Chinese “art things.”

The first was a calligraphic scroll by Yu Youren (1879–1964), a grand patriarch of the Republican era (1912–1949), on which he had written the following aphorism:

When talking of swords,

be more broadminded and tolerant;

When carving jade,

think of virtue and constancy.

The second was a stone calligrapher's seal carved in the 1960s by Feng Kanghou (1901–1983), bearing his studio name “Acceptable Unacceptable Dwelling,” and inscribed on the side with the following poem:

There is nothing good to be said of chaos and dispersion

After all these tribulations I have changed [my abode's] name to Unacceptable

The chick is lucky to survive the overturned nest

And find a dwelling for his heart

For the homeless one, home is everywhere

The Universe holds a place for me.

Carved to console myself, Feng Kanghou.

The third was a set of drawings dating to the early 1950s, comprising design drafts for the historical friezes on the Monument to the People's Heroes in Tiananmen Square (figs 1-3).

Encapsulating the pioneering spirit of the New China, the passion and breadth of vision of the Republican period, and the lonely soliloquy of a sojourner in exile, these three art things collectively introduced both the panoramic and microscopic view of China's art and history of the past century which the “Hanart 100” project seeks to explore (fig. 4). While the calligraphy scroll and the seal carving were created by noted artists, the set of design drawings for the Monument to the People's Heroes is essentially a project with no definite attribution. Yet through its very anonymity it becomes a tangible part of an organic and systematic process of naming—the search for a name, as well as a form, for a country that was as yet nameless and amorphous.

Some 2,200 years ago, when the Han dynasty was first established, the state chancellor Xiao He was placed in charge of constructing the Weiyang Palace. In the process, he gave the following advice to the first Han emperor, Liu Bang (Emperor Gaozu, 256–195 BCE): “If [the palace] is not splendid and magnificent, it will not inspire awe, and if it does not inspire awe, future generations may be tempted to alter it.”

In this embryonic phase of establishing a system of governance, an earnest process began of gathering together a variety of blueprints and drawing elements from them to produce a singular template, one that would solidify in physical form both the philosophy and history of the state, while at the same time signaling the new spirit and future path of the nation. Thus, the dozens of draft drawings solicited from all over China for the design competition of the Monument to the People's Heroes represent a valiant effort of naming at a time when the state ideology had not yet coalesced into a final form. In these drawings, all manner of design elements were thrown into the mix, including double-eaved palace roofs, steeples, jade cong tubes, statues, calligraphy, the five stars motif, military medals, flags, etc. —all part of a “symbolic operation” in which “the word was made flesh.” The ultimate goal was to come up with a satisfactory answer to the question of how to accurately and fully represent the character of the newborn nation.

In ancient China, outstanding deeds and memorable achievements were immortalized by being inscribed on stone stelae and bronze ritual vessels, but these were not “monuments” per se. The concept of raising a monument in an urban public square only became institutionalized in China after the country underwent modernization. The confluence of this modern concept with the tradition of the stone stele and the ritual vessel produced, via historical accumulation, a unique cultural genome that has a direct correspondence with the basic starting point of the “Hanart 100” project: the framework of three artworlds coexisting in China today—the globalized artworld; the traditional Chinese literati artworld; and the Socialist artworld.

fig. 1 Yu Youren (1879–1964), A Couplet with Five Characters in Running Script, 1920s, Ink on Paper, Each 227 × 64 cm

fig. 2 Feng Kanghou (1901–1983), Acceptable Unacceptable Dwelling, 1960s, Seal Carving, 2.5 × 2.5 × 10.1 cm

fig. 3 Anonymous Artists, Monument to the People's Heroes (Design Drawing), 1950–1951, Ink and Color on Paper, 56 × 81 cm

fig. 4 Panoramic view of “Hanart 100: Idiosyncrasies” exhibition, Hong Kong Arts Centre, January 2014

The Nameless Aggregate

In November 2013, when we were in the initial stages of planning the “Hanart 100” exhibition, a member of our team asked, “In curating this show are we going to follow the theoretical path of the three artworlds?” I replied that the concept of the three artworlds should be viewed as the “theoretical object” of our curatorial work. In other words, we should use the curatorial process as a methodology to tease out from within the three artworlds framework different trajectories of interpretation and understanding, and possibly an even more progressive level of theoretical reflection.

Thus our first task was to gain perceptions of and perspectives on the 100 “art things” in the exhibition. As we pored over the works, we discovered that each one of them spanned at least two of the three worlds. While the three worlds could be considered as the reverberations in art of the dominant paradigms of three different political ideologies, conversely, they also could be seen as political constructions created by three different modes of artistic awareness and technical skill. But this kind of unilateral, cause-and-effect interpretation is an oversimplification of the model, whose actual complexity lies in the way that it is continuous, interactive, conflicting and infectious over the course of several historical periods.

In fact, an extremely important point to note is that the three artworlds framework is not overly focused on the noumenon of “art” (that is to say, its focal point is not the critical evaluation of the quality of an artwork or an artist), but rather on the “three artworlds” as three different kinds of “production systems,” or end products of three kinds of historical processes; and then takes these three models as the phenomena of description and analysis—this is the framework's most fundamental and forceful raison d'être. Yet to a certain degree, our curatorial work began from outside this theoretical framework.

Thus, instead of dividing the 100 works into different “species,” we put them into different “sets,” physically separating them into the following thematic groups: Overture; The Masses; The Multitude; The People; The Word; Mao; Mountains and Rivers; Home Land; The Body; and The Net. Each one of these thematic headings comprises the smallest possible unit (the Chinese character) that contains within itself multiple implications, and that at the same time points to a vast and complex network of Chinese language concepts, both inseparable and antagonistic: The People are confronted with their external enemies; The Masses commune with the Party leadership; the emergence of a nation state is contrasted with the loss of a Home Land (fig. 5). “The Body” refers back to a poem by Song-dynasty literatus Su Dongpo, in which the poet writes: “I always regret that this body does not belong to me.” It also references the “lofty, noble, and perfect” bodies of the heroes of the Cultural Revolution operas, who sacrificed themselves to the revolutionary cause, as well as the body of the “everyman,” and the human figure that serves as a subject in traditional Western art. This is the same body that is at once the contested subject of multiple gender movements; the conceptual sarira, or “human pearl” relics of the Buddha; and the metaphysical “thing (body) in itself” (fig. 6). There was one “super-being” who was able to interact with nearly all the other communities, yet could not be integrated into any one of them: Mao (fig. 7).

In this sense, what took place in the exhibition space was not a permanent consignment of works to specific classifications, but rather a temporary arrangement; not a set of Aristotelian “genus-differentia” definitions, but rather an intra-communal “dialogue” in the sets, a series of chance encounters, examples of intertextuality, compounding, radiation, transference, and contrariety. All of this in a sense echoes the line in calligrapher Wang Xizhi's (303–361) famed scroll Orchid Pavilion Preface, in which he writes: “[Some] found satisfaction in a closeted conversation with a friend, but others, led by their inclinations, abandoned themselves without constraint to diverse interests and pursuits...” In this transient gathering or “get-together,” the works of art, again quoting Wang Xizhi, “draw upon their inner resources...the cause of their melancholy is the same as my own...”

Of course the works that faced us were only silent objects and images. And so we imagined ourselves in the role of archeologists of the future, excavating a major find of 100 specimens. Like the modern explorers who discovered the pyramids for the first time, we asked the questions: How to begin to understand them? What is it that they most want to be discovered? What aspects are of the greatest value? Even though each of the artworks was famous to some degree, as we planned the exhibition we viewed both the works and their creators as “anonymous” and “nameless,” sans titre. Our purpose was to regard them as layers of interface—as historical wounds or scars—with all the chaotic momentum of the past collapsed into them, awaiting another summoning.

fig. 5 Conceptual diagram used in planning the “Hanart 100: Idiosyncrasies” exhibition, showing The Masses, The Multitudes, The People, Home, Country (Land), The Party

fig. 6 Exhibition view of “The Body” set

fig. 7 Exhibition view of the “Mao” set

[1] See Giorgio Agamben, “Aby Warburg and the Nameless Science,” in Potentialities, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999).

The Nameless Study

During our planning process, the Mnemosyne Atlas created by the German cultural theorist Aby Warburg (1866–1929) was a major source of inspiration (fig. 8). Warburg's use of the concept of the atlas was closely related to our approach: akin to the drawing of a map, or even more, to the piecing together of a jigsaw puzzle. Each minute detail, and the gaps in between, came together to construct a vast panorama, making visible something that could not normally be grasped by the human eye, or rendered on a conventional scale. Interestingly, the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben has described Warburg's Atlas as “a scholarly discipline without a name,” and “a nameless science.”[1] As Agamben sees it, Warburg's goal in creating his own school of thought, which only after his death came to be known as “iconology” or “iconography” (although that particular definition may not be entirely accurate) was to resolve the opposition between history and anthropology, and to give form to questions that are both historical and theoretical, because images strictly speaking are neither conscious nor unconscious. Several key concepts closely related to the ideas raised in “Aby Warburg and the Nameless Science” were a constant part of our discussion: for example, the idea of yitu, which in Chinese means both “intent” and “image”—the hidden intention in a painting or an object (this ambiguous term combines the notions of “idea” or mental activity and external “form” ); and qingnian (roughly, emotion-remembrance), which came directly from Warburg's idea of “pathos,” or the German Pathosformeln (literally “emotional formulas,” but in Warburg's usage an emotionally charged visual trope). But here we should not forget that the concept of pathos comes from Aristotle's Rhetoric, specifically Section 2 of Chapter One, in which Aristotle cites three different means of proof or persuasion: logos, ethos and pathos. Pathos also lies in the interaction of the two elements of emotion and remembrance contained in the Chinese term qingnian. Finally, we considered the concepts of jiegou “structure,” zitai “attitude,” and in the historical context, qianneng “hidden potential” and shineng “active potential.” To some extent, our curatorial practice followed the same line of thought, methodology and ultimate mission as did Warburg in his day, going beyond iconology.

As we neared the exhibition's opening day, I frequently recalled Italo Calvino's novel, The Castle of Crossed Destinies. The story revolves around a group of strangers who find themselves seeking refuge together in a castle, and who all mysteriously lose their ability to speak. They then use a set of Tarot cards, arranging them in different sequences, to silently tell their own stories (figs 9a–9b). As the different characters in the novel use the cards—or rather the images on the cards—they are demonstrating semiotic theory: How the same sign appearing in a different context can produce a different set of implications, and contain an infinite number of random possibilities not limited by the specific images that appear in the pictures. But their use of the Tarot cards not only constitutes a kind of literary card game, wherein a set of images are used to produce a variety of different scenarios; more than this, they were echoing the original function of the Tarot cards—to divine the future. The Tarot employs a limited system to address limitless outcomes; it relies on the mystery of its limitations to control greater mysteries.

In the same way that the Tarot cards were spread out in Calvino's silent castle, artworks and the spaces that they inhabit also take part in a kind of silent dialogue. Bringing the special configuration of the Hong Kong Art Centre's space into our thinking, we used the space to help us generate and invent both antithetical and referential relationships among the diverse artworks. (A straightforward example is the way Geng Jianyi's Misprinted Books, which, with its over-printed texts, directly faces Fu Lin's woodcut propaganda poster Mao Zedong's Thought is Our Life Blood. This poster features multiple copies of “the one and only book” —a book that has been reprinted countless times [fig. 10].) The reflections and refractions among the different walls and surfaces, the linkages between the upper and lower floors, and the polygonal structure of the Hong Kong Arts Centre's overall layout all became part of our conceptual process (fig. 11). In particular, we treated the spiral nature of the galleries' interior architecture as a single surface, or “great wall,” that wound its way around the exhibition space, and which also allowed us to plan the final destination point—a special section exploring historical roots and dynamics. (Marx said that history rises in a spiral, but in fact in our case it descended and terminated in a spiral): this was the thematic set/section we called “The Net.” Four artworks/art things that most powerfully illustrated the most tumultuous, benighted, chaotic and insane years of the twentieth century—The Book of Yinfu, A Madman's Diary, Lingchi: Echoes of a Historical Photograph, and Red Flag Canal—were placed beneath the dragnet of Taigong Fishing for Those Willing to be Hooked (fig. 12). Surrounding all of this was the “sound wave wall,” a chronology of historical events in Mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong that took place over the past century: each event, and each work of art, was interpreted as an individual sound source, with their varying levels of strength or weakness acting like the varying pitch of a sound wave, producing echoes that continue to reverberate until the present day (fig. 13).

Within this “sound wave wall,” or “historical spectral line,” are manifested the historical symptoms of what May Bo Ching calls “structural amnesia.”8 The different events and works of art seem to be arranged in a simple juxtaposition, and history emerges as a prefabricated “readymade” with all the events and art things in superficial proximity, with no apparent connection to each other. This echoes Professor Johan Hartle's discussion concerning Global Art, as raised by thinkers such as Hans Belting, and the key concept of “peaceful coexistence.” However, by taking this concept as our starting point, we followed a thread of association back to the 1950s, when China put forward “the five principles of peaceful coexistence” as proposed by Zhou Enlai (mutual respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty; non-aggression; non-interference in each other's internal affairs; equality and cooperation; peaceful co-existence). We then counterpoised these “five principles” with other resonant instances of political theorizing: The Cold War theory of the “three worlds” put forth by Mao Zedong in the 1970s, the Clinton administration's promotion of globalization in the 1990s, and the idea of the “small country with few people” raised in the ancient Daoist text Laozi (Chapter 80), “Where people take pleasure in their food, wear fine clothing, live in safety, and are happy in their ways. Living within sight of their neighbors, they hear their dogs barking and cocks crowing, yet they never leave their hometown, and die there peacefully in old age.” Considering these diverse theories together, a pattern began to emerge, bringing with it the possibility of arriving at other, more subtle and more complex levels of perception. This was just the kind of subtle, complex understanding that we were seeking through our reading of these historical events and art things—the “echoes from the three artworlds.”

Although the exhibition has closed, our work on the “sound wave wall” of history continues. The questions we posed concerning the relationship between art and politics ultimately turned the entire exhibition inside out, revealing the true substance of the task that lay before us. In Warburg's view, artworks are like Leiden jars in which temporal energy is accumulated and preserved. Yet in the end, the ultimate purpose of Warburg's library was to lead beyond art history to a broader and more integrated form of learning. It is only by approaching the abyss that we can shed light on the fracture that is hidden within ourselves.

fig. 8 Aby Warburg (1866–1929) Mnemosyne Atlas

View of Bilderreihe for Bibliothekarstag, Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg, Hamburg, April 1927

Image courtesy The Warburg Institute, University of London

fig. 9 Narrative arrangement of Tarot cards, from Italo Calvino's novel The Castle of Crossed Destinies

fig. 10 Exhibition view: Book with over-printed texts from Geng Jianyi's Misprinted Books installation (1992) facing Fu Lin's woodcut propaganda poster Mao Zedong's Thought is Our Life Blood (late 1960s) featuring multiple copies of the “one book” (Quotations from Chairman Mao).

fig. 11 Refractions and linkages: exhibition view showing integrated use of the gallery space.

fig. 12 Exhibition view of “dragnet” configuration, showing Huang Yongping's multi-media installation Taigong Fishing for Those Willing to be Hooked suspended above Kang Youwei's ink-on-paper calligraphy The Book of Yinfu (1917); Chen Jieh-Jen's video Lingchi: Echoes of a Historical Photograph (2002); Zhao Yannian's set of 38 woodblock prints from Diary of A Madman (1985); and the 16mm Cultural Revolution film Red Flag Canal (1970).

fig. 13 Exhibition view: “Sound wave wall” area showing intersections of China's historical events and “art things” from the past century.

[1] The full text of Zhou's inscription reads: “Eternal glory to the heroes of the people who laid down their lives in the People's War of Liberation and the People's Revolution in the past three years! Eternal glory to the heroes of the people who laid down their lives in the People's War of Liberation and the People's Revolution in the past thirty years! Eternal glory to the heroes of the people who from 1840 laid down their lives in the many struggles against domestic and foreign enemies and for national independence and the freedom and well-being of the people! September 30, 1949, marking the first plenary session of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference.”

The Nameless People

That great “national treasure,” the Monument to the People's Heroes in Tiananmen Square, bears on the front side an inscription written in the calligraphy of Mao Zedong: “Eternal glory to the people's heroes,” and on the reverse side, an inscription in the hand of Zhou Enlai, in which there are multiple iterations of the phrase “eternal glory to the heroes of the people who laid down their lives in the people's war of liberation and the people's revolution.”[1] Who, in fact, are the “people's heroes?” And which “people” aren't “heroes?” Long ago, the Chinese compound noun renmin (人民) had already evolved into a single concept. Originally, ren 人 meant the rulers, the aristocracy, and min 民 meant the ruled, those who were enslaved. As we “trace” the origins of the inscriptions on the monument, the question arises of when the “people's heroes” made their first appearance. This also leads to another question: Are “the people” (min) who appear in “The People's Republic of China” (Zhonghua renmin gongheguo), the same as “the people” (min) who appear in the “Republic of China” (Zhonghua minguo)—do they have the same meaning? Has there been some migration we are not aware of? We can also trace our way back to Sun Yat-sen's “Three Principles of the People” (Sanmin zhuyi): Nationalism (minzu, lit. the nation of the people), governance by the people (minquan, lit. power of the people), and the people's livelihood (minsheng, lit. the life of the people). Are Sun Yat-sen's three min also part of one and the same entity?

Having made three thematic groupings under the headings of the Chinese terms qun 群 (The Masses); zhong 众 (The Multitude); and min 民 (The People), we began a process of juxtaposing Chinese linguistic sources, Western language translations, and contemporary usages, together with different perceptions or interpretations of the artworks, as a means of more deeply penetrating these concepts that are at once both familiar and problematic, as well as the intersections and subtleties that existed among them.

The character 群 (the masses ) is composed of two elements: 君 (jun) meaning both “gentleman-scholar” and “sovereign” and 羊 (yang) meaning sheep. In the classical poetry anthology, The Book of Songs, the character 群 is used in the following line: “Who says the shepherd has no sheep? He has a flock (群) of 300.” 群 can also be written as 羣, which shows the gentleman/sovereign resting on top of a sheep. (It is most intriguing that the Chinese words for some of the finest ethical values have a sheep element in them: 美 beauty, 善 goodness, 義 righteousness. “For he is our God, and we are the people of his pasture, and the sheep of his hand.” [Psalms: 95, 6–7]). The Christian missionaries called themselves “pastors.” “The masses” represent a quantity that increases at random, lacking in structure and interconnectedness, and only capable of exhibiting anarchic “Brownian motion;” thus the “sovereign” is in charge in name alone. In Gustave Le Bon's The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1896), the early French sociologist concluded that the “crowd” is controlled by unconscious forces. But one of the virtues of the crowd, or the masses, lies in the peculiar state of “isolation.” In the “Weiling gong” section of the Confucian Analects, the Master says: “The superior man is dignified, but does not wrangle. He is sociable, but not a partisan.” Even though there exists a constructive organic association between the individual and the masses, this associative condition does not sacrifice the “public.” Today, of course, the “parti-”(党) in “partisan” refers to the “Party.”

The late Qing-period scholar Yan Fu translated the title of Herbert Spencer's The Study of Sociology as “The Study of the Masses” (Qunxue yiyan), and John Stewart Mill's On Liberty as, literally, “Concerning the Boundary between the Rights of the Masses and the Self” (Qun ji quan jie lun). He rendered Spencer's concept of “the society and the individual” as, literally, “the national masses and the small self,” which seems like a rather profound interpretation combining the traditional and present-day Chinese understanding of the notion of “the masses,” and even anticipates the emergence of “Socialism” in China.

In the “Zhouyu” (“Discourses of Zhou”) section of the Han-dynasty text Guoyu (Discourses of the States, 5th–4th c. BCE) it is written that “Three animal forms comprise the character 群 (qun), and three human figures comprise the character 众 (zhong).” There is an evolutionary distinction of status between these two characters. The traditional form of the character for multitude, 眾 (zhong), evolved into its simplified form 众, which is made up of three “persons” with one person (人) emerging as dominant and rising above the other two; herein lies the birth of management structures and the class system. As for min 民 (the people): Well, to begin with, they're poor, and they are also min 憫 “pitiable,” because they are the workers. According to the earliest Chinese dictionary, the Han-dynasty compendium Shuowen jiezi, min 民 means “a multitude of sprouts,” thus something that requires nourishment and cultivation. It awaits genesis, and thus the Song-dynasty scholar Zhang Zai (1020–1077) wrote, “I will set my mind on serving Heaven and Earth; I will devote myself to nourishing the people.”

If the exhibition space of “Hanart 100: Idiosyncrasies” can be said to have featured a particular dialectic, tête-à-tête, or staring match, it was the one taking place between The People and Mao (as revolutionary, leader and deity; and his legacy, including the repercussions and counter-accusations)(fig. 14). On one wall, draped in a bathrobe, the Great Leader waves at the people (Tang Xiaohe's Strive Forward in Wind and Tides) while on another, a young man extends his arm in a similar fashion, although he is in fact gesturing towards an artificial “dawn” painted on a backdrop in a photography studio (Wang Xingwei's Dawn). A question arises here: Could it be that the revolution that blazed so fiercely was nothing but an empty dream, or is it rather that present-day reality is simply fraught with wishful thinking, as we look towards a false dawn (or perhaps more precisely the promise of the past) to escape from the worries and anxieties of the present?

Tseng Kwong-Chi pays a visit to the quartet of American presidents carved on the face of Mt. Rushmore, who gaze across at the Chinese leaders depicted in Liu Dahong's Sacrificial Altar. Let us consider the various mechanisms behind “The People”—serve the people, set up the people as masters of the country, stand on the side of the people; as well as the related manipulations of “The People”—arouse them, unite them, rely on them, help them, know them, protect them, educate them, raise them up, praise them, sympathize with them; and then the means of defining the opposition—separate from them, oppose them, harm them. If we then view these mechanisms and manipulations from a framework comprised of the three famous phrases from Abraham Lincoln's “Gettysburg Address”—“of the people, by the people, for the people”—we find that they fail to jibe with this framework, they are not identical to it; even as they appear to be the same, what it is about them that is so fundamentally different? The highly aroused “millions of workers and peasants” in Fang Zengxian's oil painting make eye contact with the hooligans (mang) of Fang Lijun's Cynical Realist painting (fig. 15). (It is interesting here to note that the character for mang, 氓, is composed of two elements: 亡 wang “lost” and 民 min, “the people”). Placed before the monumental triptych of Fang Zengxian, Liu Dahong and Tang Xiaohe—a kind of sacrificial altar to Mao—is Zhao Yannian's woodblock print of Ah Q, a tragic and pathetic character created by Lu Xun (fig. 16). Dragged through the mud and nearly crushed in the baptism of the revolutionary period, the pre- revolutionary Ah Q emerges as a new kind of hardened hooligan (mang) in the manner of Fang Lijun. Such hooligans or vagrants begin as “common people” (min), but due to harsh physical realties and psychological pressures, they are forced to the sidelines, and become rootless “hooligans,” “the lost.” This almost seems like a kind of biological evolution completed through social revolution.

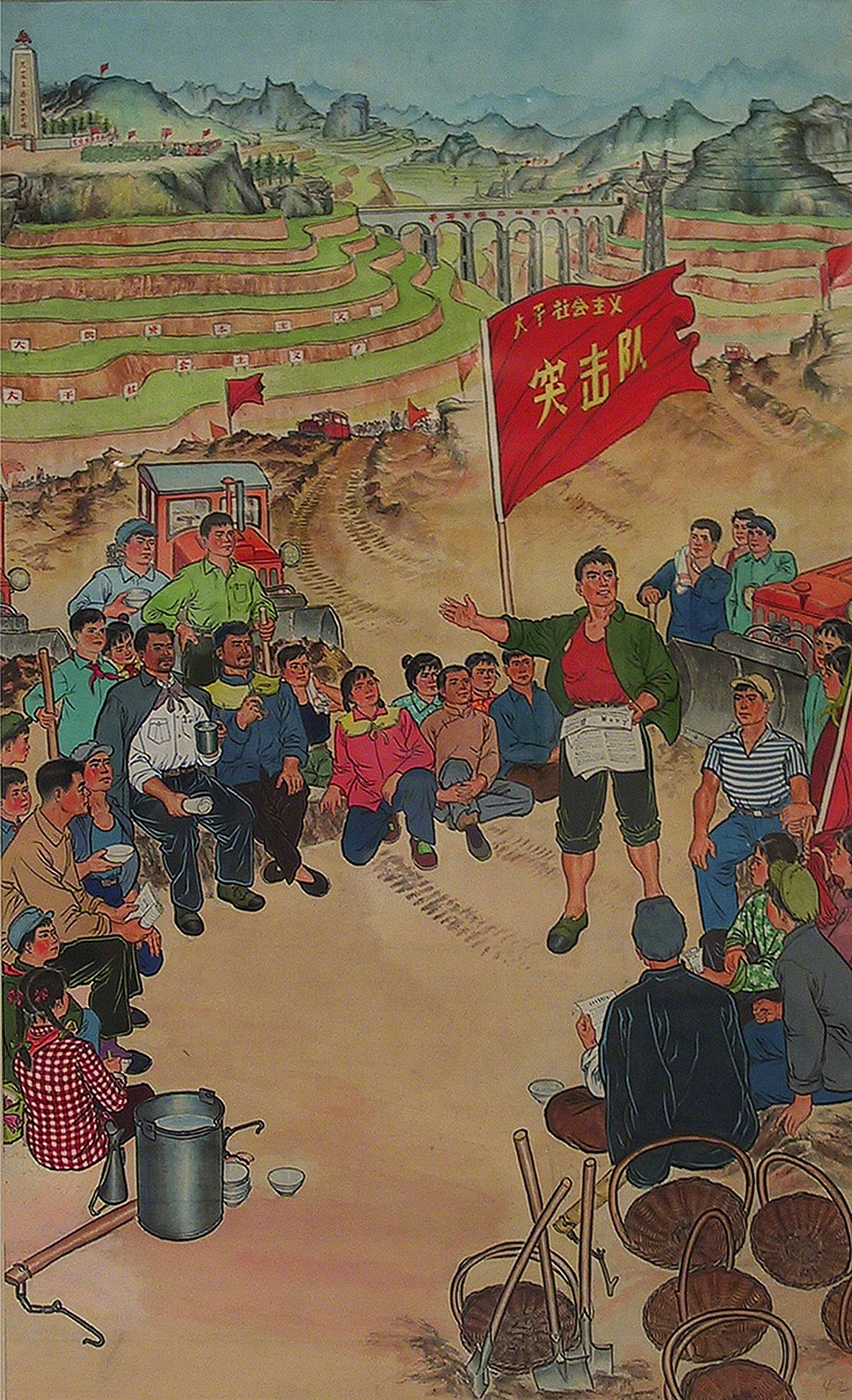

Let's turn our attention to a group of completely unrelated artworks: Press Gang of Able-Bodied Men and Rise Up from Li Hua's Raging Tide series; Zhuang Hui's photograph, A Memorial Group Photo of the Entire Crew of the Road Greening Administrative Station in Anyang, Henan Province, 13th October 1997; the anonymous artist's Huge Practice on Socialism; and Zheng Guogu's Life and Fantasies of Youth from Yangjiang (figs 17–20): when brought together into one set these disparate works trace the pictorial evolution of the collective/community over the course of the past century in China; the “hundred names,” or common people, move from enslavement and oppression to “Wherever there is oppression there is resistance!” (Engels, Mao); to the collectivized “great masses;” to “the people” who were to completely transform the world; and finally, to the “great multitudes” who live only for consumption and entertainment.

fig. 14 Exhibition view: “The People” set facing the “Mao” set.

fig. 15 Exhibition view: “The People” set facing the “Mao” set: Fang Zengxian's Arouse Millions of Workers and Peasants (1968), Fang Lijun's Series II, No.1 (1991–1992), Liu Dahong's Sacrificial Altar, Tseng Kwong-Chi's Mount Rushmore (1986), Tang Xiaohe's Strive Forward in Wind and Tides (1971), Wang Xingwei's Dawn (1994).

fig. 16 Exhibition view: “Ah Q” at the feet of the “Mao” set.

fig. 17 Li Hua (1907–1994) Raging Tide No. 3: Rise Up (top) and Press Gang of Able-Bodied Men (bottom), 1947,Woodblock Prints

Each: 19.5 × 27 cm

fig. 18 Anonymous Artists,Huge Practice on Socialism, Late 1960s,Ink and Color on Paper,135 × 68 cm

fig. 19 Zhuang Hui (b. 1963),A Memorial Group Photo of The Entire Crew of The Road Greening Administrative Station in Anyang, Henan Province, 13th Oct 1997 (detail), 1997,B/W Photograph 8.5 × 111 cm

fig. 20 Zheng Guogu (b.1970),Life and Fantasies of Youth from Yangjiang (detail), 1995–1998,Contact Print, Color Photograph,61 × 106 cm

At the same time there is a visual dialogue taking place between min 民 “the people” and zhong 众 “the multitude.” The oracle bone character for min shows an awl piercing an eye ①. Perhaps that injured eye belongs to a slave, despite the fact that the slaves could and did rebel against their masters. “The people do not fear death; thus it is useless to threaten them with death.” (Laozi). The modern scholar Guo Moruo believed that min 民 “the people” evolved from the character 盲 mang, “blind,” and thus it was necessary to “enlighten the minds of the people,” to awaken them and enable them to see the light of the truth and the future. The earliest form of the character 众 “the multitude” is ②, three peasants toiling under the noonday sun, which evolved into ③, wherein the sun has become an all-seeing, all-knowing eye, perhaps that of “Big Brother,” and the overall image is that of a ruler overseeing his underlings (a situation that gradually evolved into the notion that “the masses have sharp eyes” ).

In a and b we have two eyes, seeing eye-to-eye, silently glowering at each other. One characteristic shared by the etymologies of the three characters for “the masses,” “the multitudes” and “the people,” is that in each case, the principal subject is under observation by an external force. There is a “superior” who “oversees” what is taking place below. In these situations, everybody is looking over his shoulder, everyone is visible to everyone else. At the same time, the images will only be seen through the distant view, so they are truncated and cannot be named.

The objects remain together; the people have scattered. All the artists have departed, and their artworks hold their breaths. An exhibition is a one-time gathering. This assembly of 100 art things—or in fact, any art exhibition (regardless of which art world it represents), like every CMG New Year's Gala (where several different worlds gather to be entertained at the same time)—can be seen as a form of popular “folk art.” What does “folk” mean? Whether it is the globalized contemporary art world, the traditional art world of the literati or the socialist art world, it seems that all have their roots in the “folk.” Is “folk” a fourth dimension, lying outside the realm of the three artworlds? This dimension is not an independent world of its own, functioning on the same plane as the other three worlds; it is more like the “earth” from which the three artworlds draw to build their constructs, and the common soil which they all share. Does “folk” have an antonym, an opposite? Perhaps the “three artworlds” fulfill that role. “Folk” stands apart from officialdom, government, and authority; “folk” presents a challenge to what is international, fashionable, and new wave; and “folk” is generally incompatible with refined taste, scholarly pretensions, and intellectualism...The common soil of this life-giving, primal wilderness, is saturated with the tensions of self-contradiction. Confucius said, describing the situation in his own age, “When the rites are no longer practiced [in the court], seek [the truth, a better life] in the wilderness.” For us, this may be both our place of origin, and our final destination.

One by one, we have assigned names to the nameless stars and planets, and created constellations in the emptiness. This nameless aggregate of The Masses, The Multitude and The People have left behind their long, slow, meaningful glances, and their gaze seeks to penetrate through the mists of time (fig. 21). The poet Bei Dao (a contributor of one of the Hanart 100 “art things” ), wrote in his poem, The Answer,

A new conjunction and glimmering stars

Adorn the unobstructed sky now;

They are the pictographs from five thousand years. They are the watchful eyes of future generations.

①②③

fig. 21 Composite image of gazing eyes

Translation by Don J. Cohn and Valerie C. Doran

小.jpg)