2012

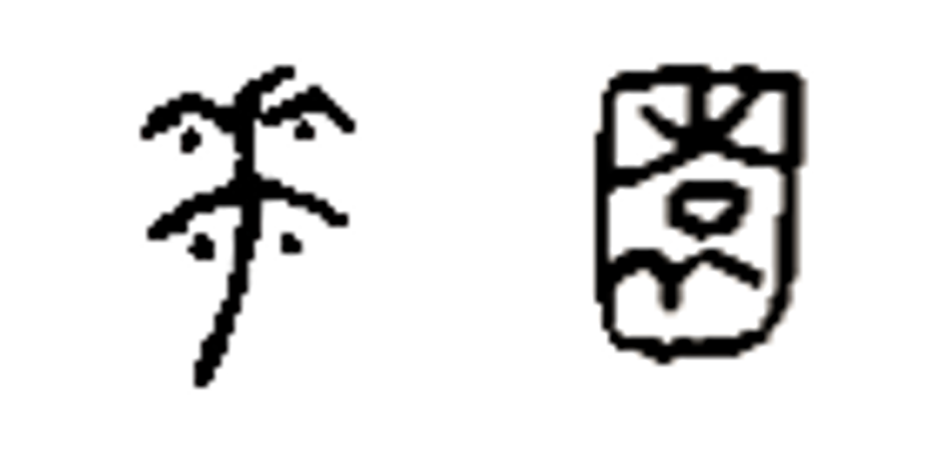

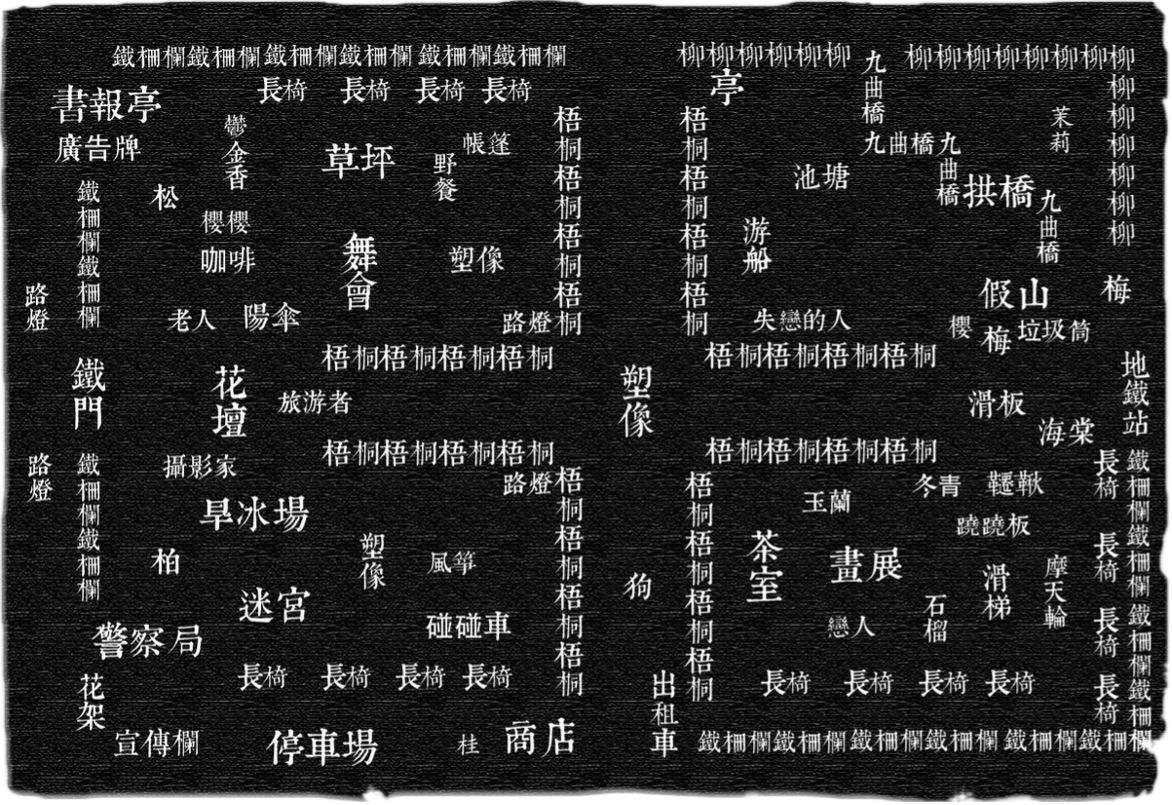

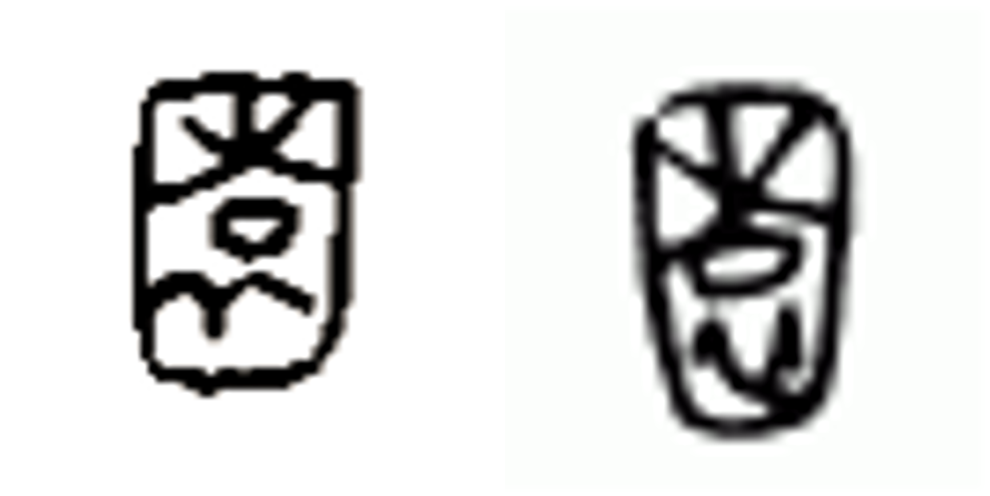

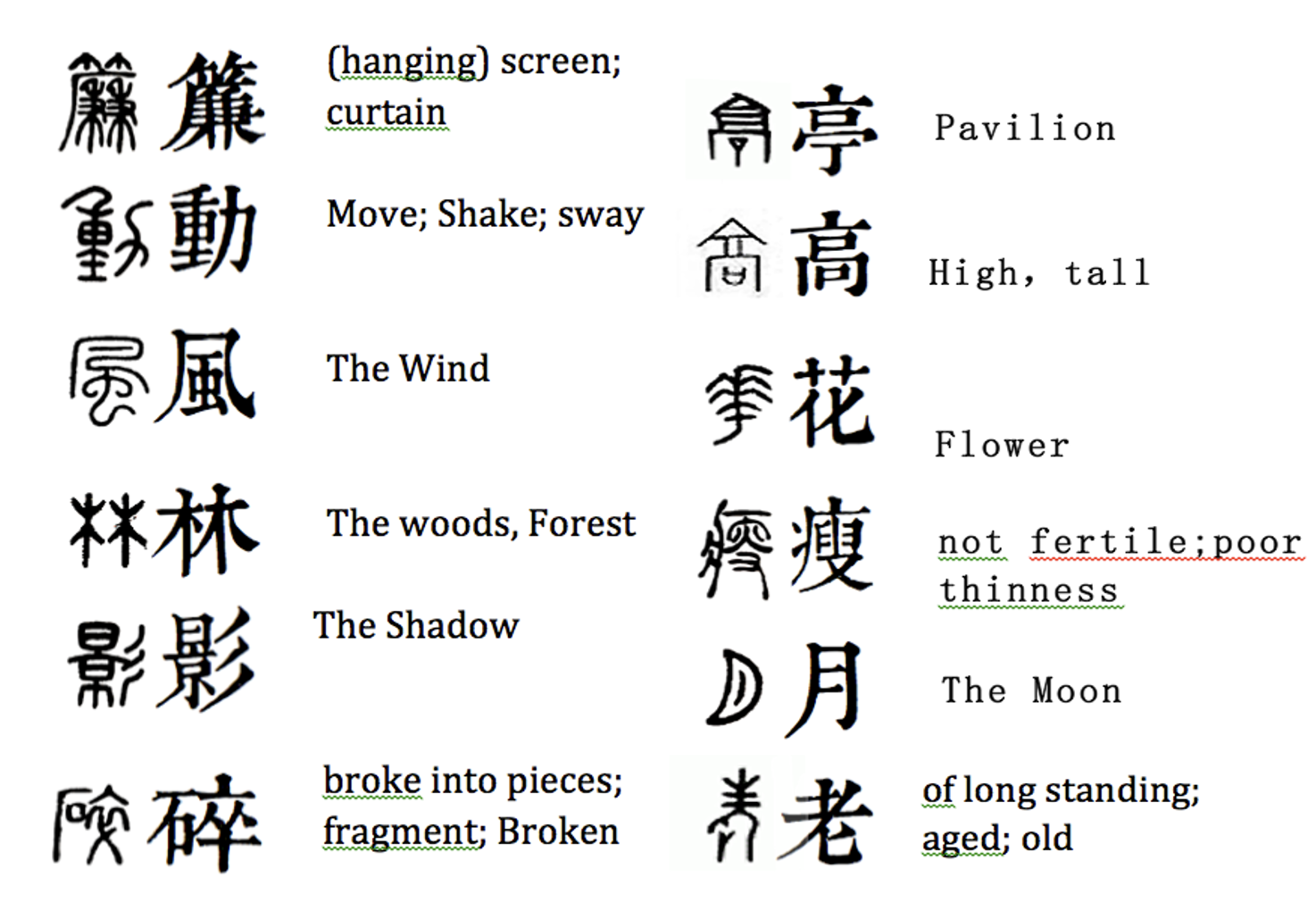

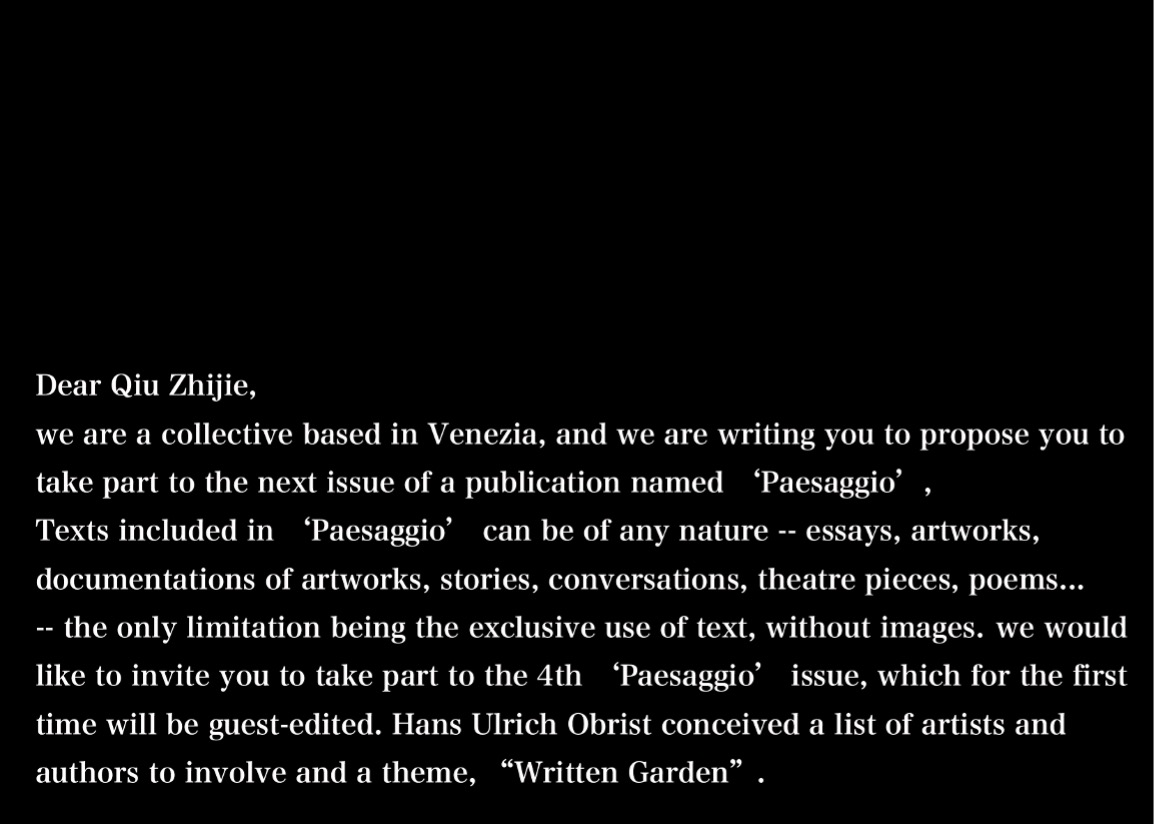

The magazine Paesaggio invited me to make a description about scenery and garden only with words but not pictures, which is almost impossible for me as a native Chinese speaker. As pictograph that have been in use for several thousand years, most Chinese characters are already pictures in themselves, such as the two characters “花園” (huayuan, “garden” in Chinese):

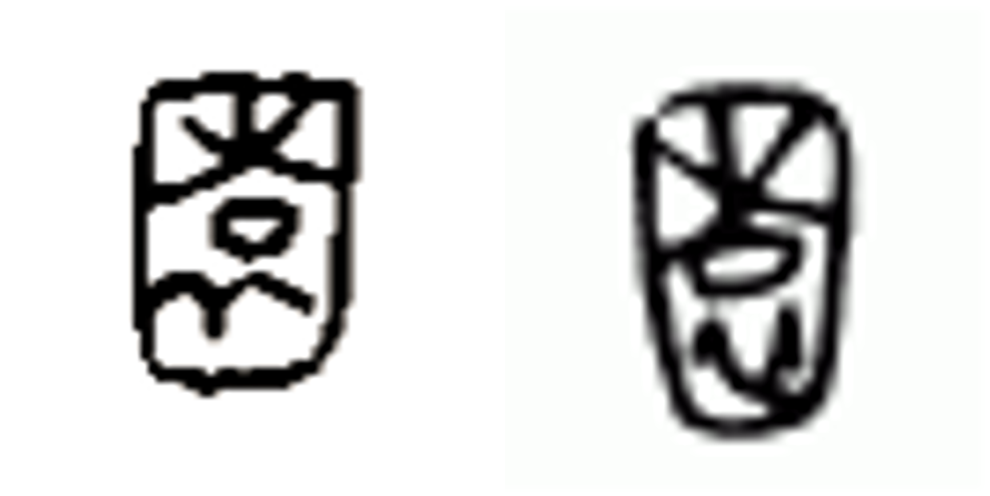

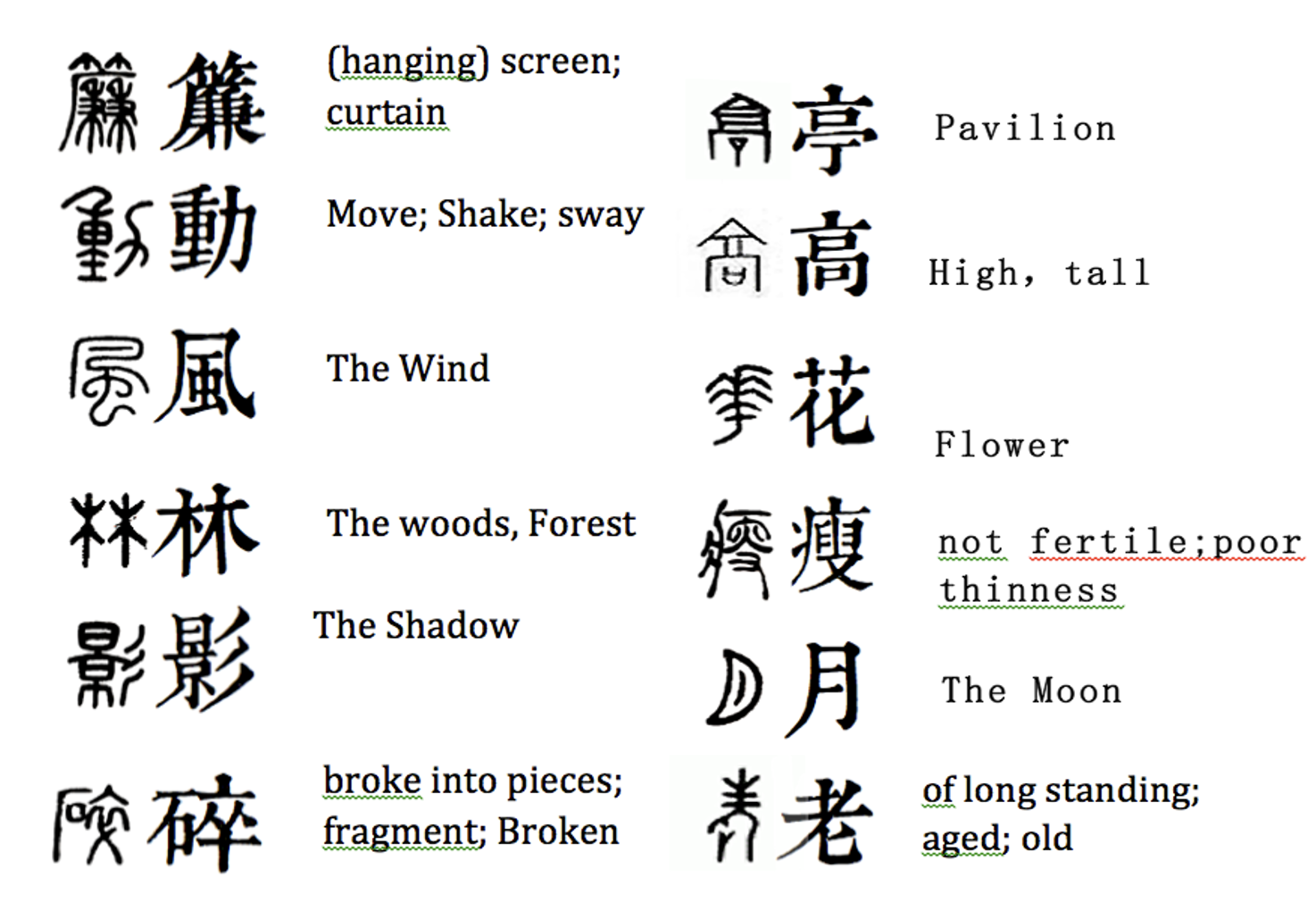

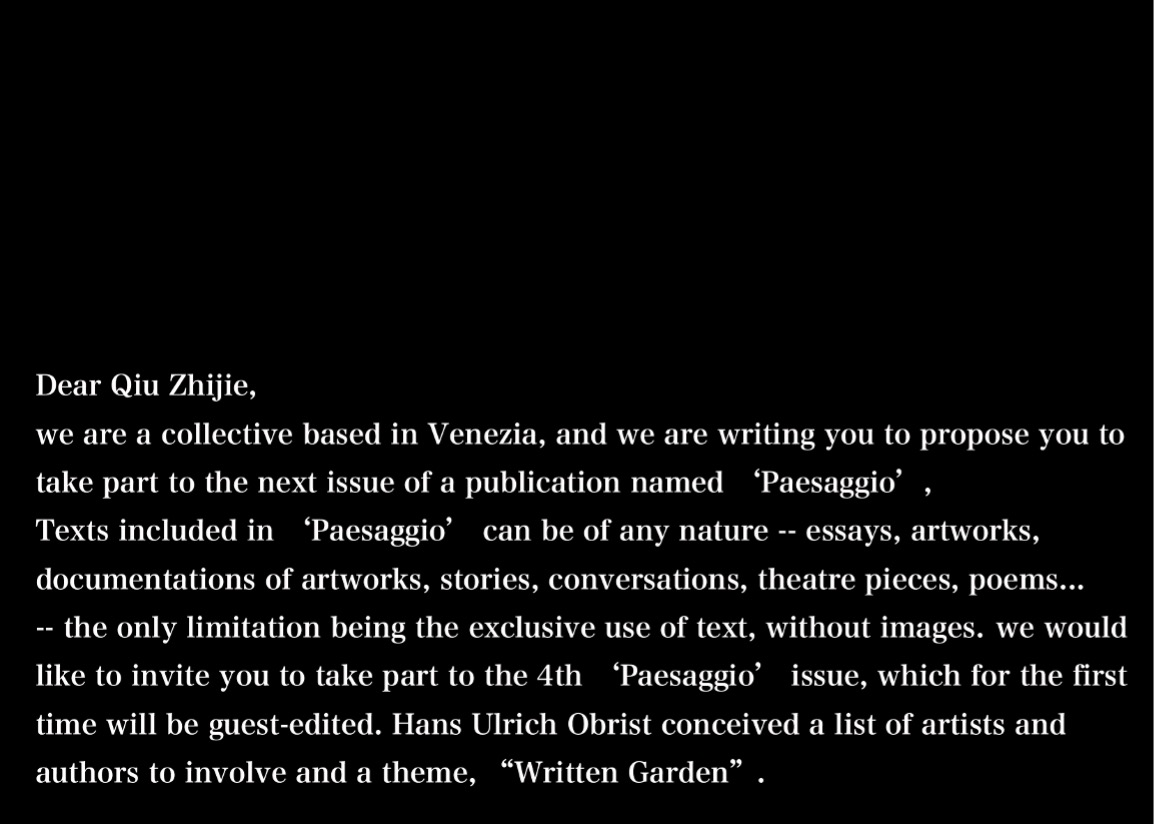

No need to go far back, we come to the characters very close to pictures:

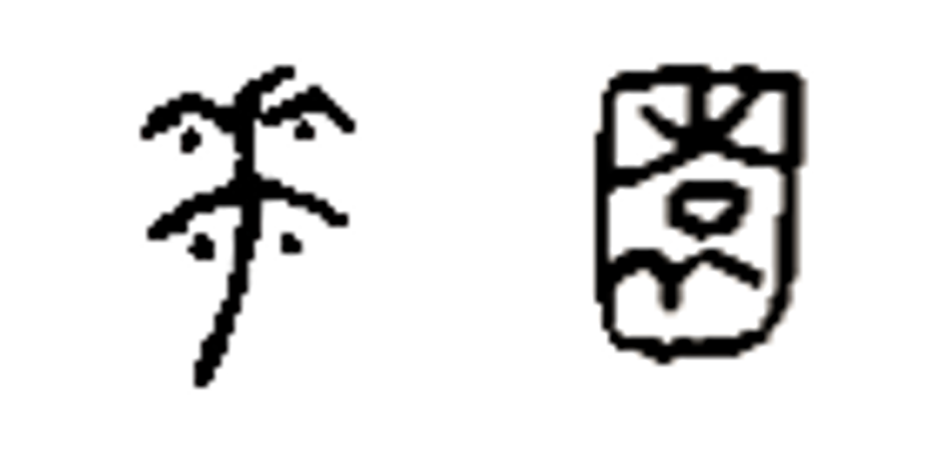

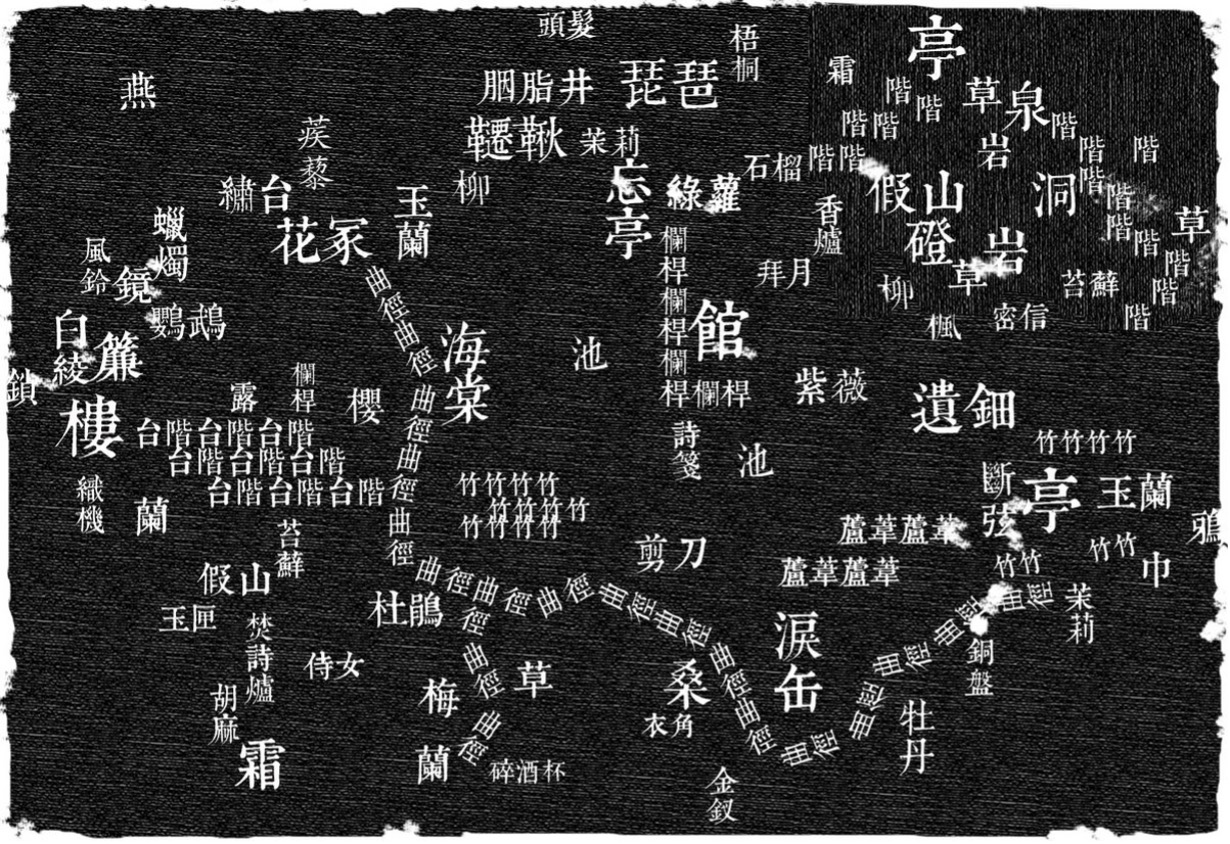

And even pictures in full sense:

In this garden, there are fence walls, grass and trees, and a pond in the center, round at first, and then reshaped into square. In front of the pond, there is even a person in clothes. His vision drops among the flowers and trees staggering far over the pond. Watching the trees casting light and dark shadows on the walls, he draws their silhouettes silently with a brush in his heart. With a sigh, he knows that he still cannot really reach the level of the artistic conception his master once mentioned when he was alive. He hears the sound of the wind outside the walls, which is like that of a piece of metal being pulled on a stone plate, or that of a flute blown by someone on the city wall, or that of laughter from the night market. Subconsciously, he tightens his collar.

His left lapel presses over the right one. Opening to the right, the whole collar looks like the shape of the letter “y.” Only the “barbarian” Hu people in the ancient north China would do it the other way.

He walks in his study and sits down in front of the desk. The moonlight has turned cool, and the ink in the inkstone is a bit coagulated, so he breathes out onto the inkstone for several times before picking up the brush and dipping it in the ink. He recalls the feasts and literary gatherings in the summertime in this garden, during which his friends were sitting beside the zigzag brook, and the one who got the floating wine cup would immediately compose a poem. He recalls the arguments they have had regarding whether the fish are really as happy as they appear to be in the water remain unresolved. And he also recalls the chess games which are, like this garden, always full of secrets, and seem otherworldly. Even though these good friends are far from each other today, they share the same waning moon in the sky. But how is the woman who once stood together with him in front of the window and counted the birds flying back home?

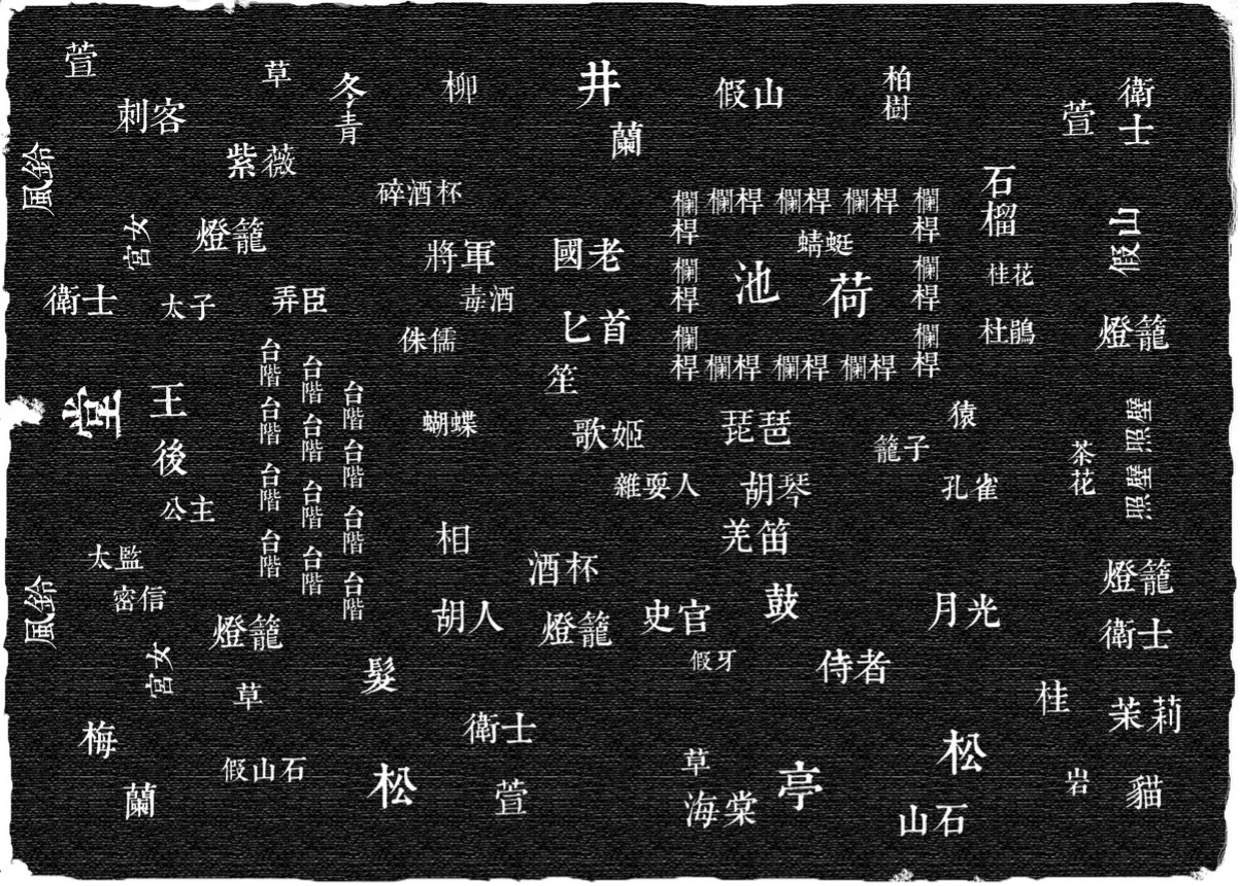

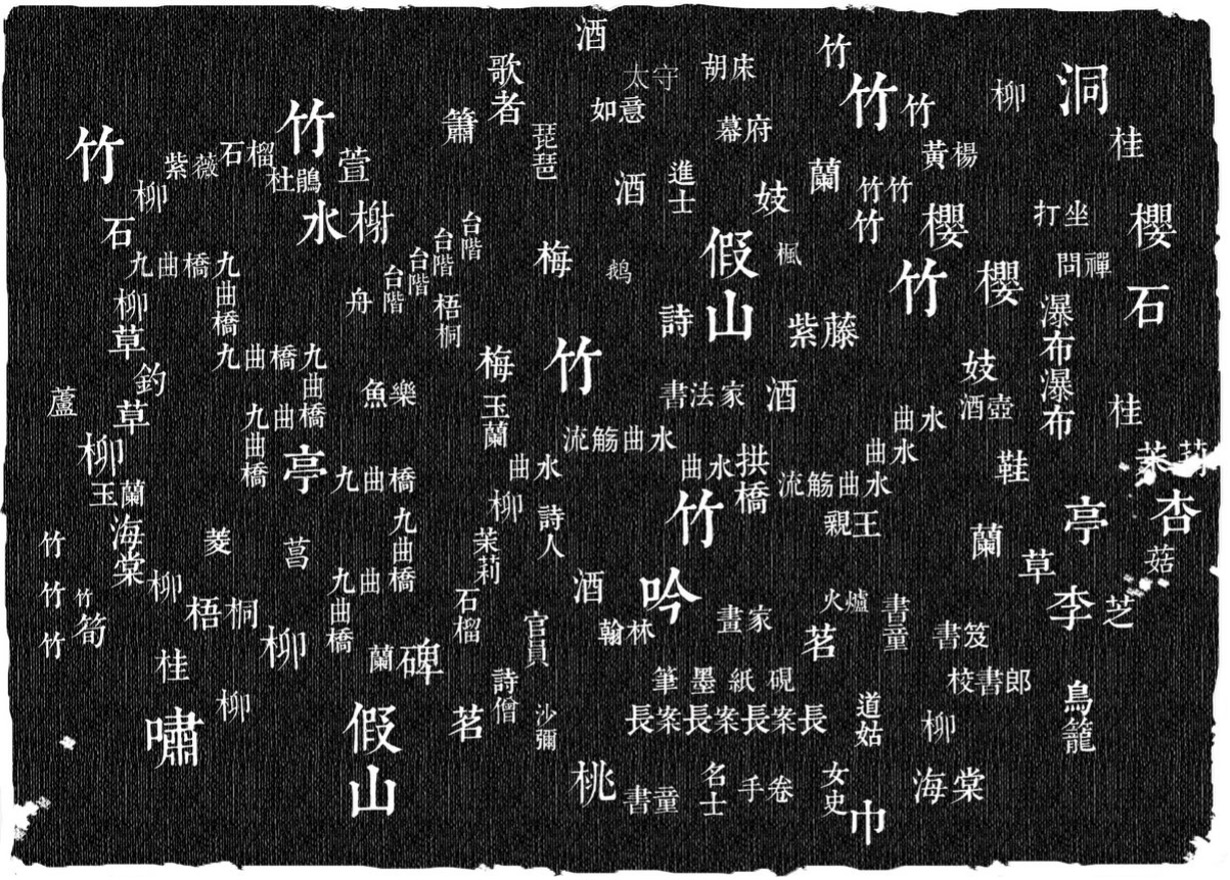

He scribbles down these characters on the paper:

Putting down the brush, he looks at these characters, which seem not written by him at all. He feels that on the top of his brush is not ink, but a kind of developing solution, which just reveals the characters that have been written secretly on this paper ever since the ancient time. For the first time, he feels kind of uneasy, as if being besieged firmly by these characters, just like by the walls of this garden. He has not walked out of this garden for long, but in fact, he has been spending his whole life here. Nevertheless, this garden is even more strange for him. The zigzag paths always make him lost, and the rockeries change forms in the twilight every day. At deep night, he can hear the sounds of the grass and trees growing, as well as that of the crunchy rockeries being weathered, mixed together with the tedious and long-last undertone of the moving celestial bodies. This garden is so profound that there might be secrets of poetry and painting hidden in every corner. While the angles between the water surface and the rockeries are designed strictly according to the principles of mathematics and music. Although rains change the water depth, the rockeries might be submerged or exposed in different ways, the scenery here always look perfect. Before today, he has never felt it necessary to leave this garden. It is not at all a garden in the world, but one contains the whole world. The world outside of the walls is just an imperfect mirror image of this garden.

For years, his only active communication with the outer world is through the letters with poems he threw into the flowing water. The water welled up from a spring in the garden, and his poems were poured out from his wine jar. The two were synchronized in extraordinary profusion at the nights of full moon. It was just the spring water and poems flowed out the walls attracted the wind and butterflies from the outer world.

He puts down his brush and inclines it on the “mountain-like brush holder” on the desk. The brush holder is a two-inch fine porcelain in the exact shape of the Chinese character “山” (shan, “hill” in Chinese) in the style of inscription on oracle bones, looks like three connected peaks, and like the English letter “W” as well. The two valleys are right for supporting the bamboo body of the brush, so as to prevent the fluid ink from soiling the desk. The hair on the tip of his brush is made of the hair on the tail of weasels in the east Liao province and the beards of rats in the east of Guangdong province. In the seal character “筆” (bi, “brush” in Chinese), the two sets of bamboo leaves at the top tells us the material of the brush body: bitter bamboo growing in Huzhou by the Taihu Lake in Zhejiang province. On the lower part of the vertical body of the character is the loose brush hair, and in the middle is a right hand holding the body. The four virtues of a brush is “to be sharp, even, round and sturdy;” the rule of holding a brush is “to press by fingers firmly while keep the palm released and hollow, and to leave the wrist horizontal and palm vertical;” in the final analysis, with the heart just, the brush is in correctitude. This character “筆” tells such apparently.

The Chinese character “墨” (mo, “ink” in Chinese) draws out the picture of a strong fire and soot accumulating on the roof of a shed. The method of making the ink on his brush tip is: burning the old pine branches from the Yellow Mountain, collecting the black soot of them from the roof, mixing the black soot with the deerhorn glue from Dai prefecture (produced through stewing the deerhorn with water for a long time till it condensed into glue) in Huizhou district under the Yellow Mountain, adding muskiness, and smashing it for thousands of times. The pine soot once suffused an exquisite fragrance all around now becomes an ink ingot, the fragrance of which no longer suffused around, but solidified in waiting. It leans on the edge of the inkstone, which is made of a stone from a puddle in Duanzhou district of Guangdong province. This kind of stone is perennially soaked under water, so is with fine and hard quality, and is as mild and smooth as jade. It does not wear the brush hair, and is all right to grind ink with a little water as that in one’s breaths.

The paper he wrote on just now is made of the fibre of day lilies in Jing county of Anhui province. The yellow flower of this kind of plant is called “golden needle,” and forgetting grass. It tastes delicious in soup. Eating it, one forgets love.

The living room of his mother in the north direction is gloomy, and is good for planting day lilies outside.

Looking at the “mountain-like brush holder” on his desk, he sees all the peaks in the world. This desk is the real garden. The garden out of the window is just the mirror image of that on the desk. In this garden, there is a stone awake from under the water, pine trees from the Yellow Mountain, bamboo forest from Huzhou district, and grass from Jing county growing densely in the shade of an architecture. Among the plants, there is a lucky deer from the north strolling around, and a mysterious weasel that can stand up as a man does.

The pine trees from the Yellow Mountain turned into smoke, and into solid ink ingot, and with dew and spring water mixed in the inkstone made in Duanzhou district, the ink ingot is ground into liquid ink, coagulates on the paper made of day lilies, and then becomes poems and paintings. But all his poems and paintings are just for understanding the Yellow Mountain.

The peaks are as perfect as a bonsai, each angle of them being like carefully arranged by a master of garden according to a famous ancient painting. While the garden right in the front, obviously a masterpiece of a garden master in the previous dynasty, appears to be a work of the Nature. Both the two are too perfect as dreams to be believable.

In the winding corridor in the garden, there are windows in different shapes in the walls. The round, square, and fan-shaped windows are just like painting frames hanging on the wall. Each time looking over through these windows, he sees not only exquisite brushworks and ink colours in distinct schools and successions, but also long prefaces and postscripts. Besides, in the part of the wall turning back to the north, a lot of steles from different dynasties are inlaid. The steles record in detail real stories happened in this garden, which forces him to believe that this is not in dream. The rubbings of those steles are right now on the left of his desk. All these rubbings together make up with a map of this garden with texts.

He puts his sight on that pile of rubbings. Moving away the inkstone and brush holder, he takes up the first piece of rubbing to examine carefully.

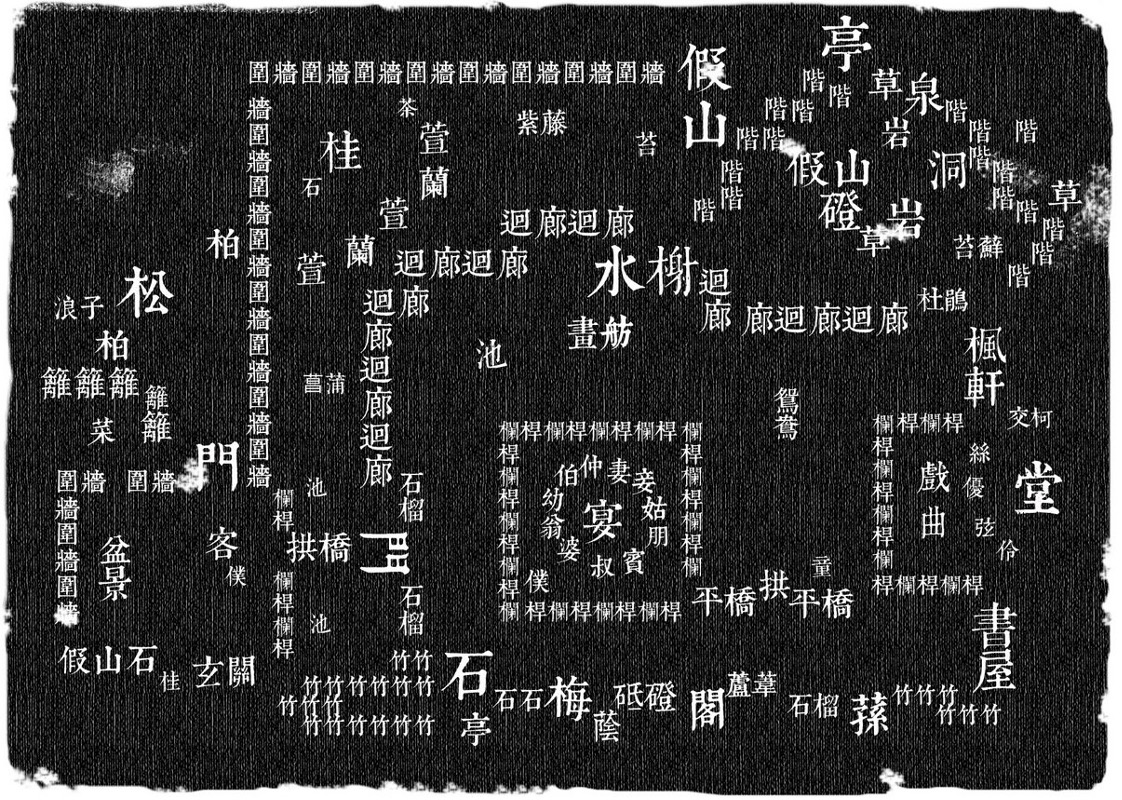

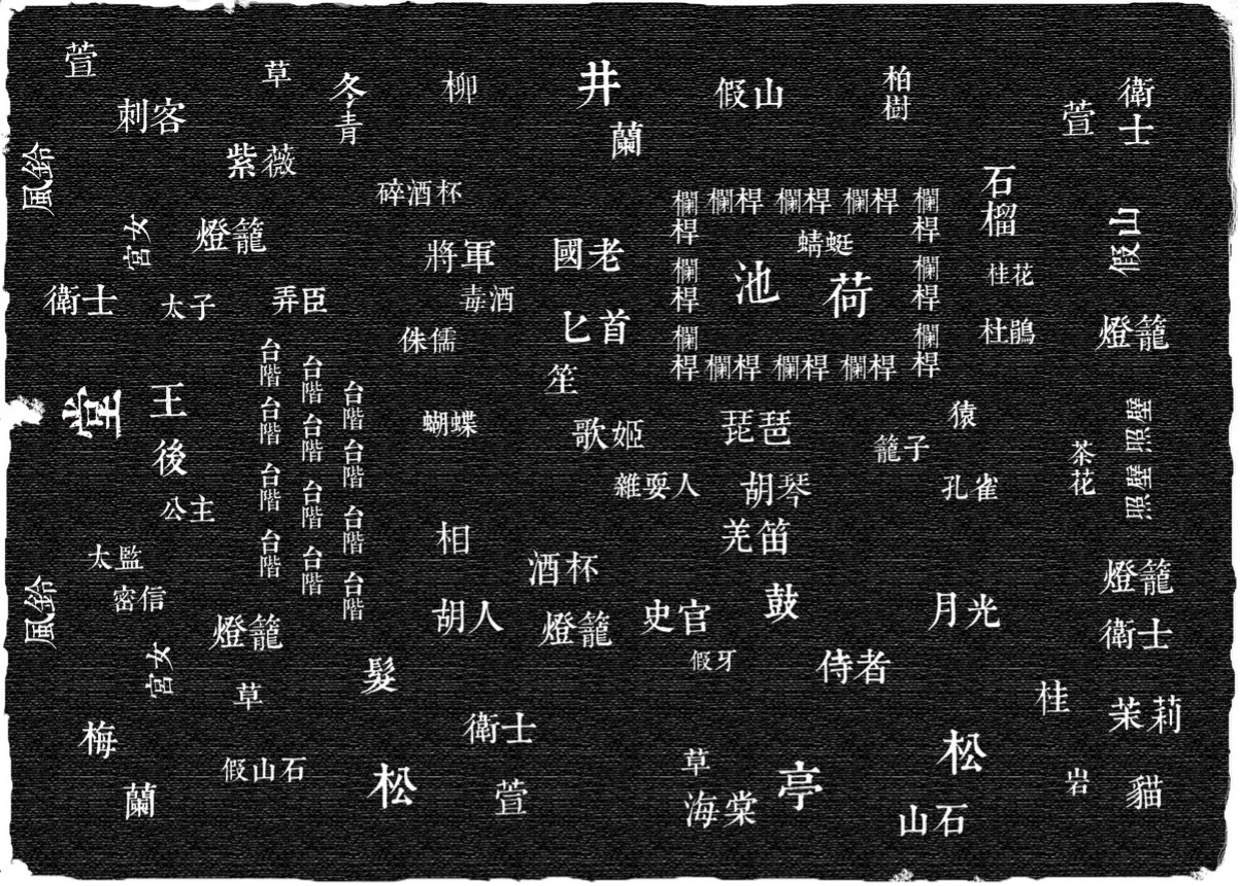

It records a royal banquet happened in the garden when it was just established:

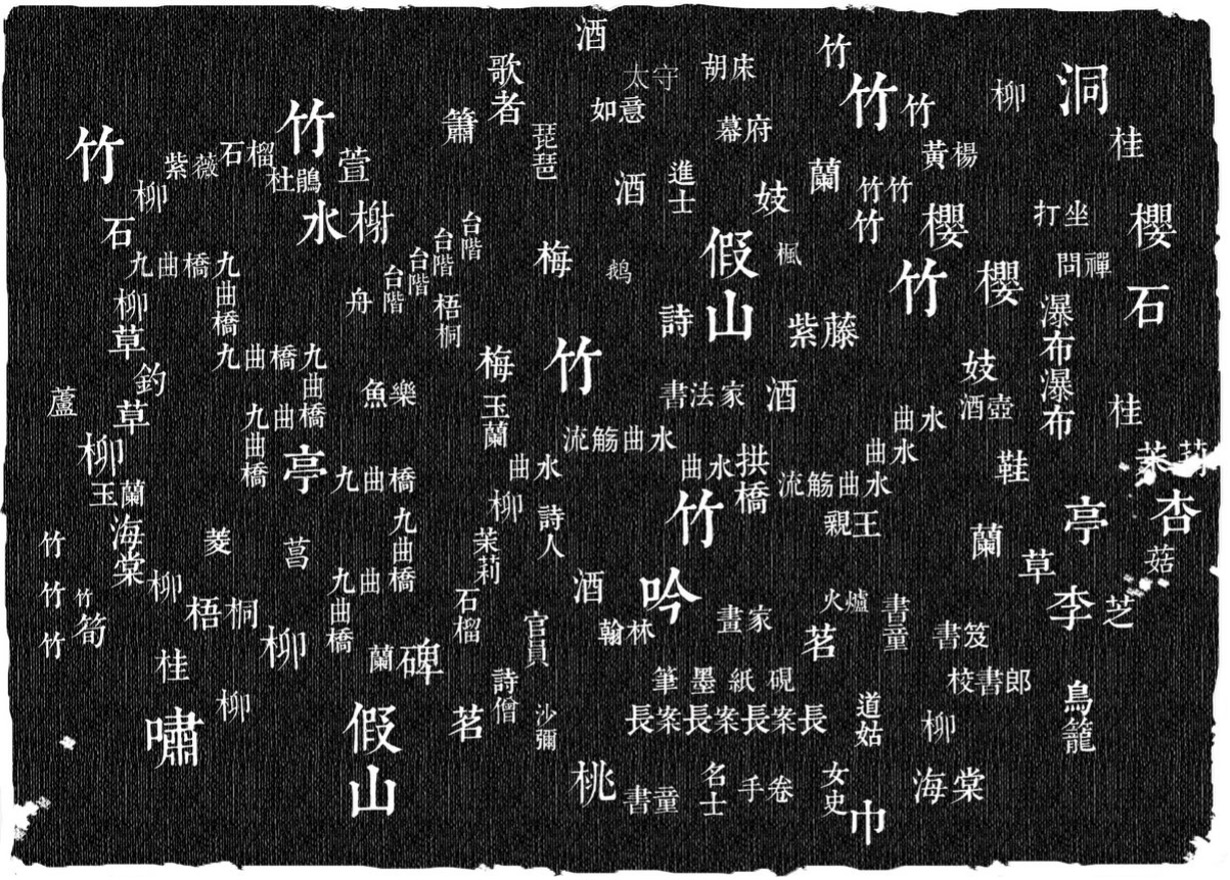

The second piece records a known gathering of poets more than one thousand years ago.

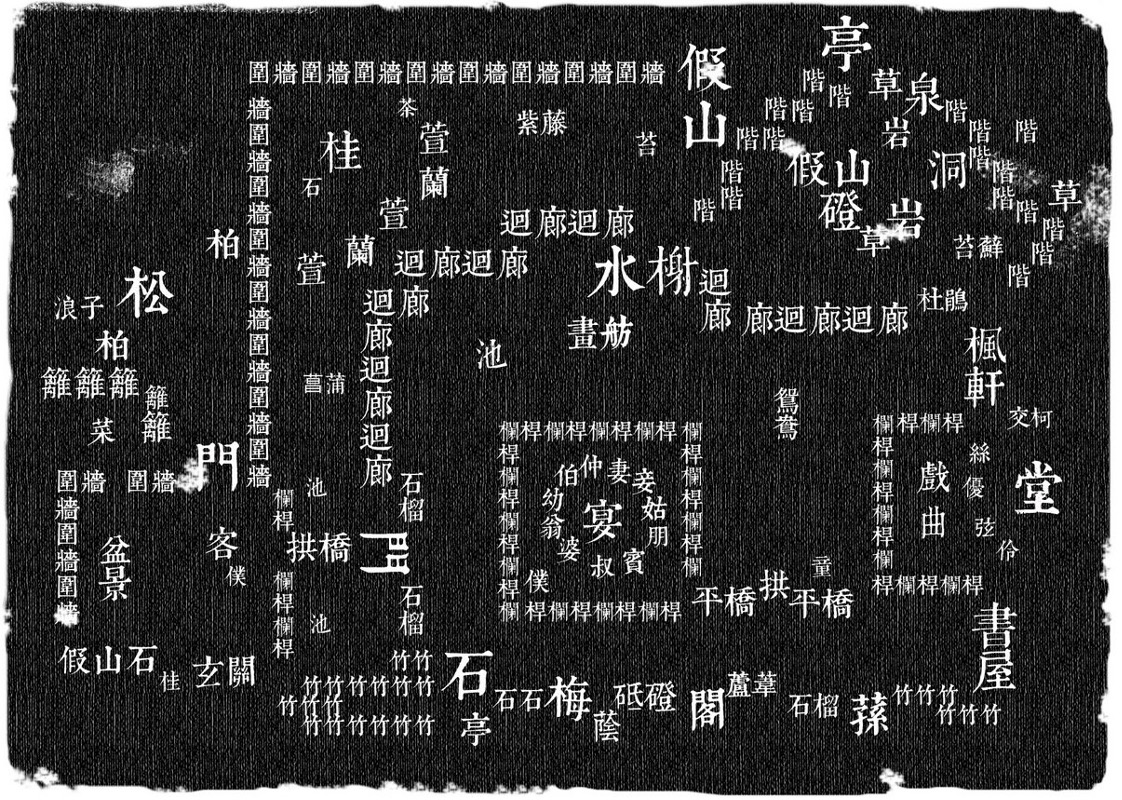

The third piece records the story of a family owned this garden 400 years ago.

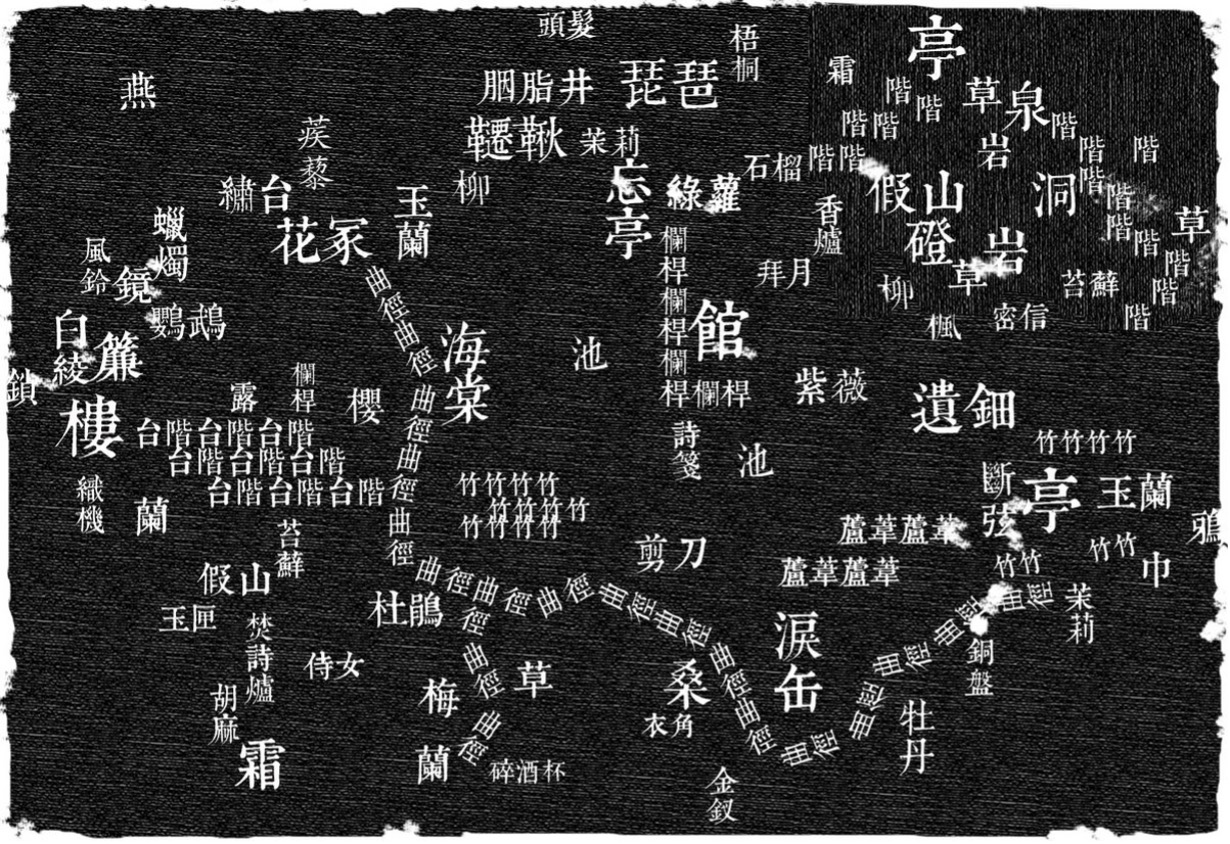

The fourth piece weirdly records stories happened in this garden about various young women, who seemed suffer a lot in their lives.

The fifth piece is about the history of snow in this garden.

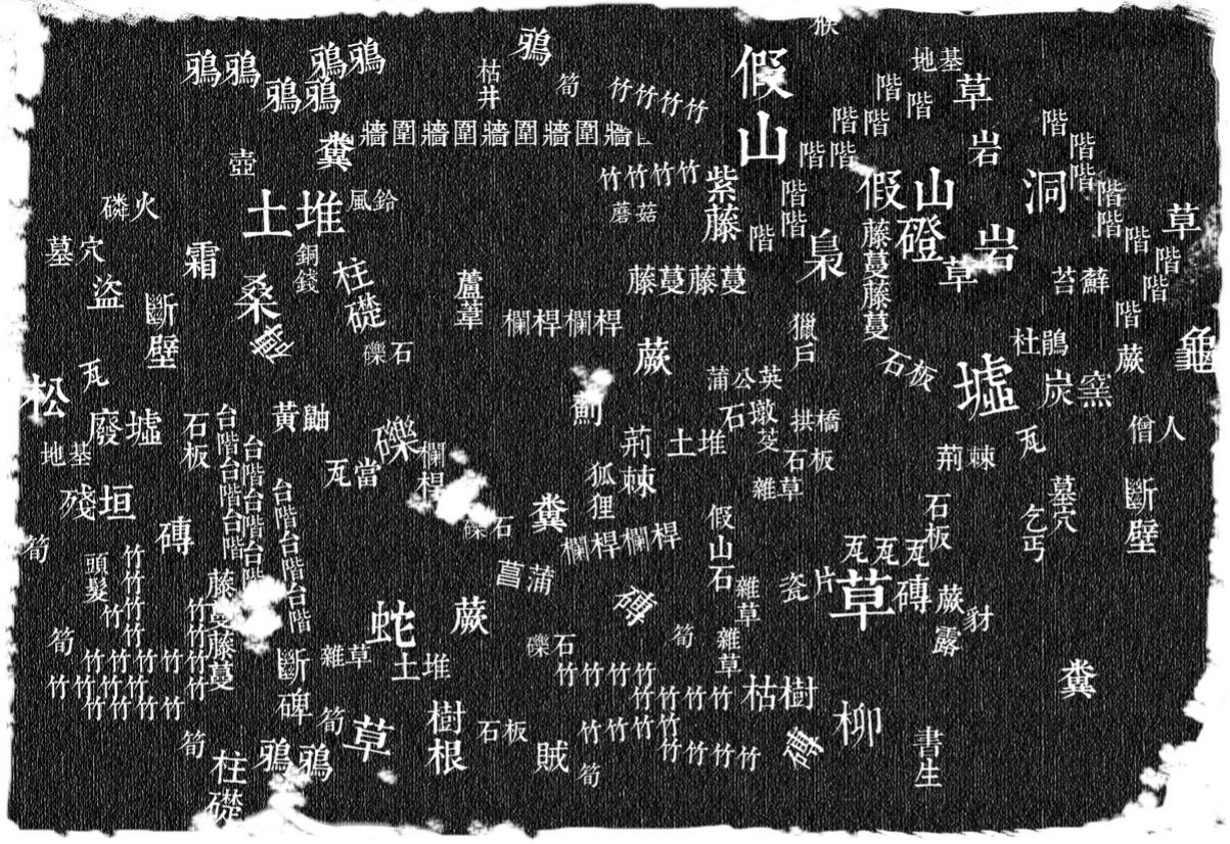

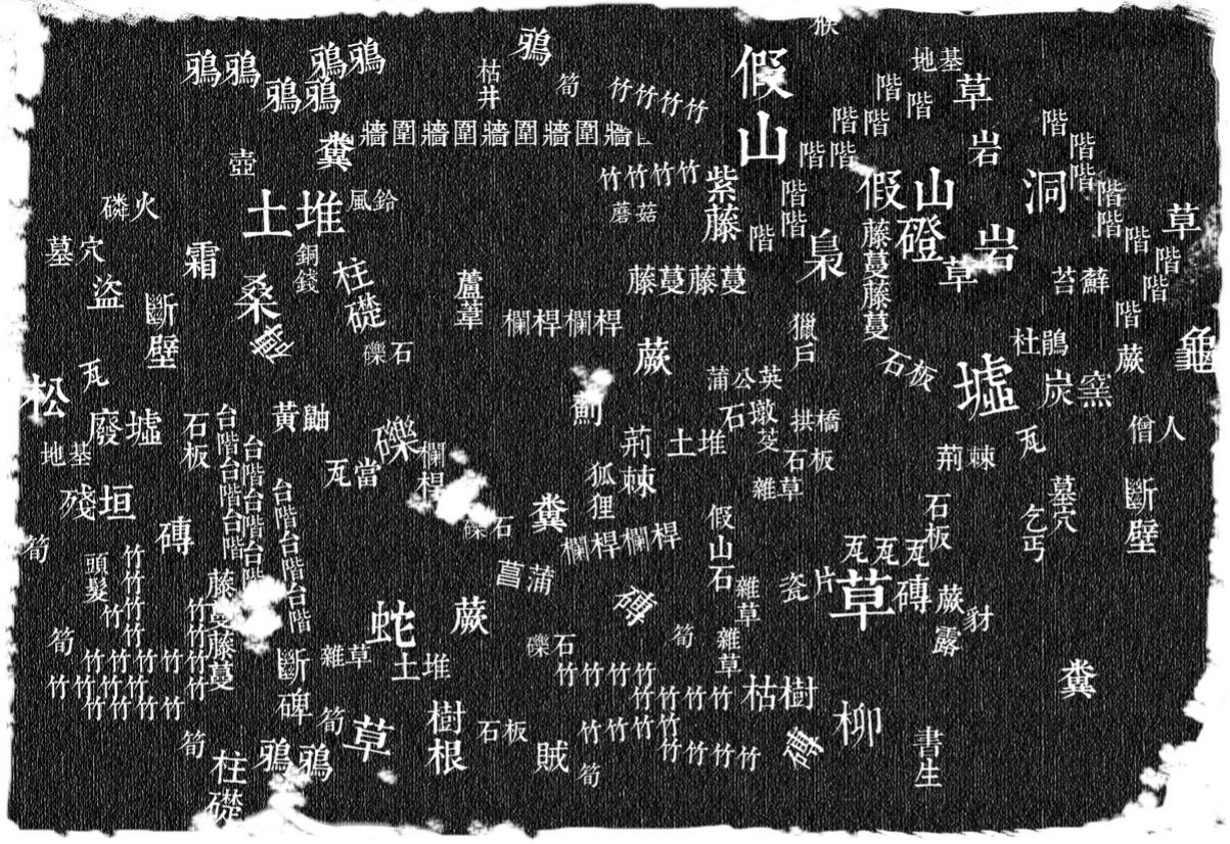

What the sixth records seems like a garden in waste. He does not remember if he has ever seen this stele in the wall, nor know if it is this garden that it records, but just looks like it in structure. It is probably about times of its being in waste in the long history, or just a prediction.

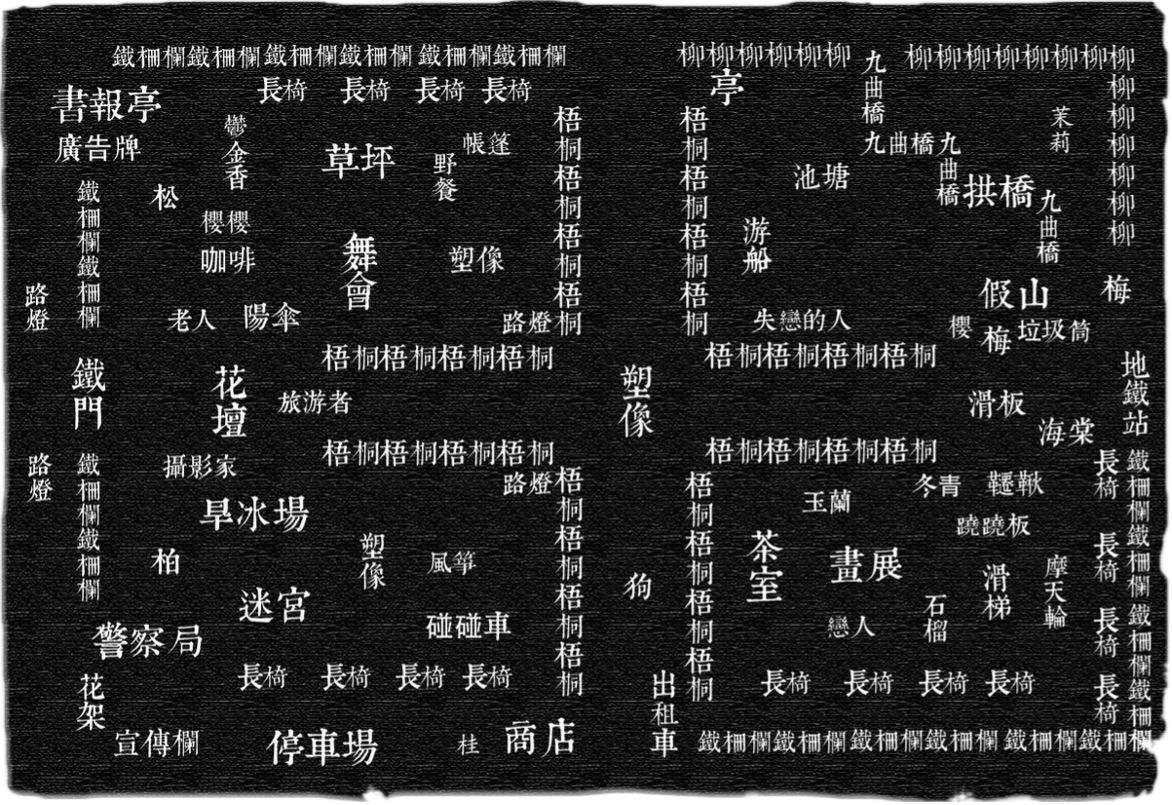

The seventh describes many things he has never experienced. Seemingly, it is a rubbing from the future.

How come a stele foretelling the future inlaid in the wall of the corridor in the garden? How did this picture come to his desk?

He decides to investigate it over in the corridor of steles. Leaving the desk, he puts on his overclothes, and enters the garden. This moment in the garden, the moonlight has already been warded off by the high fence walls, the insects’ shrill sound, fragrance of ink and grass and trees in the air, together with the pavilion, rockeries and corridor, liquefy into gel-like fluid in the deep night. He gropes his way in the dark for a long time, but has not found those steles. In the recent years, whenever too much reading brings him the feeling of being drunk, the situation of getting lost in the garden happens frequently. When he passes by the square-shaped window for the third time, he hears “tinkle.” That is the sound when he receives an email. The square window lights up, and he sees the email below:

Notes:

1 王King 后Queen将军genera弄臣A court jeste史官historiographer 相Minster 胡人 刺客triggerman 太子 Croen Prince 歌姬singing girl 投降者 侏儒midget 杂耍人variety show 公主princess 太监eunuch 侍者waiter 卫士bodyguard假牙denture笙 pipe匕首dagger密信secret letter发hair 台阶steps 堂hall 假山石rockery design 池塘Pool 栏杆balustrade酒杯goblet琵琶lute毒酒poisonous wine 鼓drum照壁screen wall 风铃windbell 亭pavilion月光moonlight石榴megranate桂花fragrans杜鹃azalea茶花camellia紫薇jacaranda芝weeds兰orchid 萱day lily松pine蜻蜓dragonfly 蝴蝶butterfly孔雀peacock猿ape笼子cage碎酒杯broken goblet 猫cat 灯笼lantern

2 竹bamboo 九曲桥zigzag bridge 石stone 妓prostitute 侍女maid 长案long table 笔brush 墨ink 纸paper 砚inkstone 书童houseboy 书法家calligrapher 画家painter 亲王prince 太守mayor 校书郎book editor 女史scholarly lady 道姑Taoist nun 僧monk 名士personage 官员official 翰林member of the Imperial Academy 进士a successful candidate in the highest imperial examinations 沙弥young monk 碑stele 钓rodster 打坐meditation 问禅Zen arguing 手卷hand scroll 菱water chestnut 茗tea 诗歌poem 泉spring 吟recite or compose poetry 啸growl 诗人poet 鞋shoe 酒壶flagon 桃peach blossom 李plum 杏apricot 鹅goose 柳willow 桑mulberry冬青holly; Chinese ilex 樱sakura 玉兰Magnolia denudata 黄杨Chinese littleleaf box 茉莉jasmine 野草weeds 荷lotus 梅plum blossom 海棠Malus spectabilis 柏cypress 紫藤wistaria 流觞曲水drifting cups on the Zigzag river 鱼fish 梧桐Chinese parasol 瀑布waterfall 笋bamboo shoot 拱桥arch bridge 舟boat

3 围墙inclosure wall 门gate 玄关screen wall 画舫gaily-painted pleasure-boat 篱fense 菜vegetable 轩lofty house with windows 盆景miniascape 妻wife 妾concubine 宴banque 姑young lady 婆old lady 叔uncle伯elder uncle翁greybeard 仲the second son 幼baby 朋friend 宾respected guest 客visitor 童kid 优伶actor or actress 浪子dissipator 戏theater 曲melody 丝弦stringed instruments 屋room 阁boudoir 馆guesthouse 荫shade (of a tree)仆servant 苔moss 回廊cloister 砥flat stone 磴stone steps 水榭waterside pavilion 菖蒲calamus 洞cave 岩rock 鸳鸯mandarin duck 荪bamboo fungus

4 楼boudoir 蜡烛candel 铜钱copper cash 露dew 霜frost 曲径rambling forest paths 焚诗炉poems burning furnace 花冢flower tomb 拜月pray to the moon 泪缶tears jar 诗笺paper with poems 忘亭pavilion of forgetting 遗钿lost hair ornament 帘curtain 更漏sound the night watches 绿萝Chinese wistaria 牡丹peony 韆鞦swing 织机loom 绣台embroidery tower镜子mirror 香炉censer 铜盘copper pan 玉匣jade box 剪刀scissors 白绫white silk brocade金钗golden hairpin 胭脂 rouge荆棘thorn 蒺藜caltrop 锁lock 燕 swallow 鸦crow 鹦鹉parrot 芦苇reed 巾handkerchief

5 狐狸fox 墓穴grave 断碑broken stele 废墟ruins 黄鼬weasel 豺jackal枭owl 龟turtle 蛇snake 砖brick 断壁cliff 残垣cliff 石板flat stone 瓦当eaves tile 瓷片pieces of porcelain 瓦tile 柱础plinth of pillar 地基subgrade 磷火wildfire 蓟thistle 猎户huntsman 乞丐beggar 炭窑charcoal kiln 粪dejecta 土堆mound 蕨fernbrake 蒲公英dandelion 芟mow (grass) 砾石gravel树根tree root 枯树withered tree 藤蔓cirrus 盗bandit 贼thief 书生scholar 枯井a dry well 石墩frusta 僧人monk

6 铁门iron gate 铁栅栏iron fence 游船pleasure-boats 长椅bench 滑梯children's slide 摩天轮Ferris wheel 花坛parterre 梧桐phoenix tree 草坪lawn 舞会dancing party 野餐picnicker 帐篷 tent书报亭 news-stand 警察局police office 迷宫maze 画展art exhibition 宣传栏knowledge publicize billboard 广告牌billboard 地铁站subway station 花架pergola 商店store 旱冰场dry skating arena 老人old man 出租车taxi 茶室tea house 咖啡cafe 碰碰车dodgems 塑像statue,monument 松pine 柏cypress 路灯street lamp 风筝kite 垃圾筒garbage can 郁金香tulip 跷跷板seesaw 滑板skateboard 阳伞parasol 摄影家photographer 旅游者tourist 恋人lovers 停车场park area 失恋的人one who disappointed in love 狗dog

Translated by Tang Xiaolin

The magazine Paesaggio invited me to make a description about scenery and garden only with words but not pictures, which is almost impossible for me as a native Chinese speaker. As pictograph that have been in use for several thousand years, most Chinese characters are already pictures in themselves, such as the two characters “花園” (huayuan, “garden” in Chinese):

花園

No need to go far back, we come to the characters very close to pictures:

And even pictures in full sense:

In this garden, there are fence walls, grass and trees, and a pond in the center, round at first, and then reshaped into square. In front of the pond, there is even a person in clothes. His vision drops among the flowers and trees staggering far over the pond. Watching the trees casting light and dark shadows on the walls, he draws their silhouettes silently with a brush in his heart. With a sigh, he knows that he still cannot really reach the level of the artistic conception his master once mentioned when he was alive. He hears the sound of the wind outside the walls, which is like that of a piece of metal being pulled on a stone plate, or that of a flute blown by someone on the city wall, or that of laughter from the night market. Subconsciously, he tightens his collar.

His left lapel presses over the right one. Opening to the right, the whole collar looks like the shape of the letter “y.” Only the “barbarian” Hu people in the ancient north China would do it the other way.

He walks in his study and sits down in front of the desk. The moonlight has turned cool, and the ink in the inkstone is a bit coagulated, so he breathes out onto the inkstone for several times before picking up the brush and dipping it in the ink. He recalls the feasts and literary gatherings in the summertime in this garden, during which his friends were sitting beside the zigzag brook, and the one who got the floating wine cup would immediately compose a poem. He recalls the arguments they have had regarding whether the fish are really as happy as they appear to be in the water remain unresolved. And he also recalls the chess games which are, like this garden, always full of secrets, and seem otherworldly. Even though these good friends are far from each other today, they share the same waning moon in the sky. But how is the woman who once stood together with him in front of the window and counted the birds flying back home?

He scribbles down these characters on the paper:

Putting down the brush, he looks at these characters, which seem not written by him at all. He feels that on the top of his brush is not ink, but a kind of developing solution, which just reveals the characters that have been written secretly on this paper ever since the ancient time. For the first time, he feels kind of uneasy, as if being besieged firmly by these characters, just like by the walls of this garden. He has not walked out of this garden for long, but in fact, he has been spending his whole life here. Nevertheless, this garden is even more strange for him. The zigzag paths always make him lost, and the rockeries change forms in the twilight every day. At deep night, he can hear the sounds of the grass and trees growing, as well as that of the crunchy rockeries being weathered, mixed together with the tedious and long-last undertone of the moving celestial bodies. This garden is so profound that there might be secrets of poetry and painting hidden in every corner. While the angles between the water surface and the rockeries are designed strictly according to the principles of mathematics and music. Although rains change the water depth, the rockeries might be submerged or exposed in different ways, the scenery here always look perfect. Before today, he has never felt it necessary to leave this garden. It is not at all a garden in the world, but one contains the whole world. The world outside of the walls is just an imperfect mirror image of this garden.

For years, his only active communication with the outer world is through the letters with poems he threw into the flowing water. The water welled up from a spring in the garden, and his poems were poured out from his wine jar. The two were synchronized in extraordinary profusion at the nights of full moon. It was just the spring water and poems flowed out the walls attracted the wind and butterflies from the outer world.

He puts down his brush and inclines it on the “mountain-like brush holder” on the desk. The brush holder is a two-inch fine porcelain in the exact shape of the Chinese character “山” (shan, “hill” in Chinese) in the style of inscription on oracle bones, looks like three connected peaks, and like the English letter “W” as well. The two valleys are right for supporting the bamboo body of the brush, so as to prevent the fluid ink from soiling the desk. The hair on the tip of his brush is made of the hair on the tail of weasels in the east Liao province and the beards of rats in the east of Guangdong province. In the seal character “筆” (bi, “brush” in Chinese), the two sets of bamboo leaves at the top tells us the material of the brush body: bitter bamboo growing in Huzhou by the Taihu Lake in Zhejiang province. On the lower part of the vertical body of the character is the loose brush hair, and in the middle is a right hand holding the body. The four virtues of a brush is “to be sharp, even, round and sturdy;” the rule of holding a brush is “to press by fingers firmly while keep the palm released and hollow, and to leave the wrist horizontal and palm vertical;” in the final analysis, with the heart just, the brush is in correctitude. This character “筆” tells such apparently.

The Chinese character “墨” (mo, “ink” in Chinese) draws out the picture of a strong fire and soot accumulating on the roof of a shed. The method of making the ink on his brush tip is: burning the old pine branches from the Yellow Mountain, collecting the black soot of them from the roof, mixing the black soot with the deerhorn glue from Dai prefecture (produced through stewing the deerhorn with water for a long time till it condensed into glue) in Huizhou district under the Yellow Mountain, adding muskiness, and smashing it for thousands of times. The pine soot once suffused an exquisite fragrance all around now becomes an ink ingot, the fragrance of which no longer suffused around, but solidified in waiting. It leans on the edge of the inkstone, which is made of a stone from a puddle in Duanzhou district of Guangdong province. This kind of stone is perennially soaked under water, so is with fine and hard quality, and is as mild and smooth as jade. It does not wear the brush hair, and is all right to grind ink with a little water as that in one’s breaths.

The paper he wrote on just now is made of the fibre of day lilies in Jing county of Anhui province. The yellow flower of this kind of plant is called “golden needle,” and forgetting grass. It tastes delicious in soup. Eating it, one forgets love.

The living room of his mother in the north direction is gloomy, and is good for planting day lilies outside.

Looking at the “mountain-like brush holder” on his desk, he sees all the peaks in the world. This desk is the real garden. The garden out of the window is just the mirror image of that on the desk. In this garden, there is a stone awake from under the water, pine trees from the Yellow Mountain, bamboo forest from Huzhou district, and grass from Jing county growing densely in the shade of an architecture. Among the plants, there is a lucky deer from the north strolling around, and a mysterious weasel that can stand up as a man does.

The pine trees from the Yellow Mountain turned into smoke, and into solid ink ingot, and with dew and spring water mixed in the inkstone made in Duanzhou district, the ink ingot is ground into liquid ink, coagulates on the paper made of day lilies, and then becomes poems and paintings. But all his poems and paintings are just for understanding the Yellow Mountain.

The peaks are as perfect as a bonsai, each angle of them being like carefully arranged by a master of garden according to a famous ancient painting. While the garden right in the front, obviously a masterpiece of a garden master in the previous dynasty, appears to be a work of the Nature. Both the two are too perfect as dreams to be believable.

In the winding corridor in the garden, there are windows in different shapes in the walls. The round, square, and fan-shaped windows are just like painting frames hanging on the wall. Each time looking over through these windows, he sees not only exquisite brushworks and ink colours in distinct schools and successions, but also long prefaces and postscripts. Besides, in the part of the wall turning back to the north, a lot of steles from different dynasties are inlaid. The steles record in detail real stories happened in this garden, which forces him to believe that this is not in dream. The rubbings of those steles are right now on the left of his desk. All these rubbings together make up with a map of this garden with texts.

He puts his sight on that pile of rubbings. Moving away the inkstone and brush holder, he takes up the first piece of rubbing to examine carefully.

It records a royal banquet happened in the garden when it was just established:

The second piece records a known gathering of poets more than one thousand years ago.

The third piece records the story of a family owned this garden 400 years ago.

The fourth piece weirdly records stories happened in this garden about various young women, who seemed suffer a lot in their lives.

The fifth piece is about the history of snow in this garden.

What the sixth records seems like a garden in waste. He does not remember if he has ever seen this stele in the wall, nor know if it is this garden that it records, but just looks like it in structure. It is probably about times of its being in waste in the long history, or just a prediction.

The seventh describes many things he has never experienced. Seemingly, it is a rubbing from the future.

How come a stele foretelling the future inlaid in the wall of the corridor in the garden? How did this picture come to his desk?

He decides to investigate it over in the corridor of steles. Leaving the desk, he puts on his overclothes, and enters the garden. This moment in the garden, the moonlight has already been warded off by the high fence walls, the insects’ shrill sound, fragrance of ink and grass and trees in the air, together with the pavilion, rockeries and corridor, liquefy into gel-like fluid in the deep night. He gropes his way in the dark for a long time, but has not found those steles. In the recent years, whenever too much reading brings him the feeling of being drunk, the situation of getting lost in the garden happens frequently. When he passes by the square-shaped window for the third time, he hears “tinkle.” That is the sound when he receives an email. The square window lights up, and he sees the email below:

Notes:

1 王King 后Queen将军genera弄臣A court jeste史官historiographer 相Minster 胡人 刺客triggerman 太子 Croen Prince 歌姬singing girl 投降者 侏儒midget 杂耍人variety show 公主princess 太监eunuch 侍者waiter 卫士bodyguard假牙denture笙 pipe匕首dagger密信secret letter发hair 台阶steps 堂hall 假山石rockery design 池塘Pool 栏杆balustrade酒杯goblet琵琶lute毒酒poisonous wine 鼓drum照壁screen wall 风铃windbell 亭pavilion月光moonlight石榴megranate桂花fragrans杜鹃azalea茶花camellia紫薇jacaranda芝weeds兰orchid 萱day lily松pine蜻蜓dragonfly 蝴蝶butterfly孔雀peacock猿ape笼子cage碎酒杯broken goblet 猫cat 灯笼lantern

2 竹bamboo 九曲桥zigzag bridge 石stone 妓prostitute 侍女maid 长案long table 笔brush 墨ink 纸paper 砚inkstone 书童houseboy 书法家calligrapher 画家painter 亲王prince 太守mayor 校书郎book editor 女史scholarly lady 道姑Taoist nun 僧monk 名士personage 官员official 翰林member of the Imperial Academy 进士a successful candidate in the highest imperial examinations 沙弥young monk 碑stele 钓rodster 打坐meditation 问禅Zen arguing 手卷hand scroll 菱water chestnut 茗tea 诗歌poem 泉spring 吟recite or compose poetry 啸growl 诗人poet 鞋shoe 酒壶flagon 桃peach blossom 李plum 杏apricot 鹅goose 柳willow 桑mulberry冬青holly; Chinese ilex 樱sakura 玉兰Magnolia denudata 黄杨Chinese littleleaf box 茉莉jasmine 野草weeds 荷lotus 梅plum blossom 海棠Malus spectabilis 柏cypress 紫藤wistaria 流觞曲水drifting cups on the Zigzag river 鱼fish 梧桐Chinese parasol 瀑布waterfall 笋bamboo shoot 拱桥arch bridge 舟boat

3 围墙inclosure wall 门gate 玄关screen wall 画舫gaily-painted pleasure-boat 篱fense 菜vegetable 轩lofty house with windows 盆景miniascape 妻wife 妾concubine 宴banque 姑young lady 婆old lady 叔uncle伯elder uncle翁greybeard 仲the second son 幼baby 朋friend 宾respected guest 客visitor 童kid 优伶actor or actress 浪子dissipator 戏theater 曲melody 丝弦stringed instruments 屋room 阁boudoir 馆guesthouse 荫shade (of a tree)仆servant 苔moss 回廊cloister 砥flat stone 磴stone steps 水榭waterside pavilion 菖蒲calamus 洞cave 岩rock 鸳鸯mandarin duck 荪bamboo fungus

4 楼boudoir 蜡烛candel 铜钱copper cash 露dew 霜frost 曲径rambling forest paths 焚诗炉poems burning furnace 花冢flower tomb 拜月pray to the moon 泪缶tears jar 诗笺paper with poems 忘亭pavilion of forgetting 遗钿lost hair ornament 帘curtain 更漏sound the night watches 绿萝Chinese wistaria 牡丹peony 韆鞦swing 织机loom 绣台embroidery tower镜子mirror 香炉censer 铜盘copper pan 玉匣jade box 剪刀scissors 白绫white silk brocade金钗golden hairpin 胭脂 rouge荆棘thorn 蒺藜caltrop 锁lock 燕 swallow 鸦crow 鹦鹉parrot 芦苇reed 巾handkerchief

5 狐狸fox 墓穴grave 断碑broken stele 废墟ruins 黄鼬weasel 豺jackal枭owl 龟turtle 蛇snake 砖brick 断壁cliff 残垣cliff 石板flat stone 瓦当eaves tile 瓷片pieces of porcelain 瓦tile 柱础plinth of pillar 地基subgrade 磷火wildfire 蓟thistle 猎户huntsman 乞丐beggar 炭窑charcoal kiln 粪dejecta 土堆mound 蕨fernbrake 蒲公英dandelion 芟mow (grass) 砾石gravel树根tree root 枯树withered tree 藤蔓cirrus 盗bandit 贼thief 书生scholar 枯井a dry well 石墩frusta 僧人monk

6 铁门iron gate 铁栅栏iron fence 游船pleasure-boats 长椅bench 滑梯children's slide 摩天轮Ferris wheel 花坛parterre 梧桐phoenix tree 草坪lawn 舞会dancing party 野餐picnicker 帐篷 tent书报亭 news-stand 警察局police office 迷宫maze 画展art exhibition 宣传栏knowledge publicize billboard 广告牌billboard 地铁站subway station 花架pergola 商店store 旱冰场dry skating arena 老人old man 出租车taxi 茶室tea house 咖啡cafe 碰碰车dodgems 塑像statue,monument 松pine 柏cypress 路灯street lamp 风筝kite 垃圾筒garbage can 郁金香tulip 跷跷板seesaw 滑板skateboard 阳伞parasol 摄影家photographer 旅游者tourist 恋人lovers 停车场park area 失恋的人one who disappointed in love 狗dog

Translated by Tang Xiaolin