2016

1

On January 18th 2006, the evening before the opening of the World Culture Forum (WCF), a crowd of intellectuals and activists gathered in the city of Bamako to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Bandung Conference. Since then, in the spirit of the Bandung Conference, the “Bamako Proposal” was delivered, the aim of which was to create a popular, pluralistic and multipolar historical subject, to transcend the opposition between the North and the South, to go beyond the rules and values of the capitalism and imperialism, and to construct “the common” from diversity.

The “Bamako Proposal” explicitly highlighted ten concrete themes: global political organizations, economic organizations of the world system, the future of agricultural societies, establishing a united front for working people, a mode of regionalization that served the interests of the people, an authentic social democracy, gender equality, environmental-friendly management of the Earth’s resources, a democratic administration for the media and cultural diversity, and the democratization of international organizations.

Ten years have passed. What has the situation become now?

During the WCF, Samir Amin and others already clearly remarked that the “Bandung Spirit” had inevitably been worn out. In those countries in the South, the governments willingly gave up social democratic process and settled with neoliberalism, the result of which was a return to the path of populism, or rendering a service to the imperialism, and, in both cases, democracy break faith with the people. In those countries in the North, the Left and the Right have already reached an agreement around economic liberalism, which is replacing social democracy with the American version of minimal democracy.

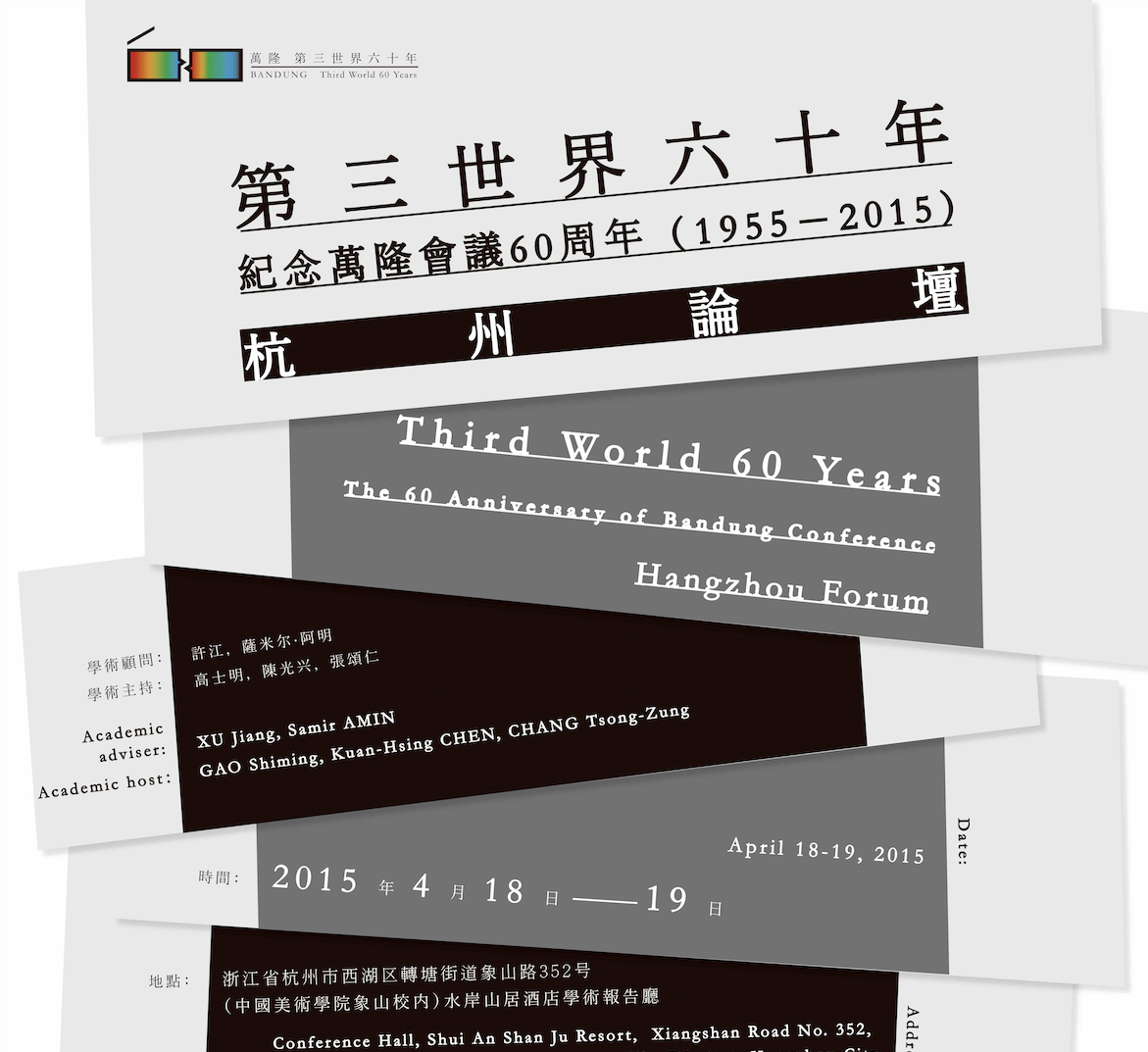

Last year, we have held the “Bandung/Third World 60 Years” Hangzhou Forum, and I have met many of those who are also seated among here today during that event. During my summary statement for that conference, I have especially pointed out that the old form of internationalism no long suffices; in fact, the symbol for international solidarity in the 19th century, the song l’internationale, is now only sung when one is in a state of drunken ecstasy. The “Bandung Spirit” has already been worn out by the production/consumption system of global capitalism; and the people, having been isolated by the conflicts of interest between nation states and by the international chain of supply and demand, have been transformed into competitors and enemies of each other. The people have been re-split under the dual structure of imperialism and nation state, broken and discretized in the entanglement of the history of colonialism and the Cold War, and distributed and integrated in the globalized network of production and consumption --- the fate of the people, in the words of the artist Chen Chieh-Jen, is in “global imprisonment, and local exile”.

In such predicament, we cannot help but to ask: in the new situation of the 21st century, what exactly is the ground and kernel of a new alliance and a new solidarity? Was it only the “development” and “win-win” figured out according to profit that could unite us?

Through the establishment of the Bandung School, we are intentionally raking up the past --- bringing up again “Asia-Africa-Latin America” and the Third World. We just must cling to it, for the history should not be let go easily. Because this project that has not been carried out yet but already announced a failure was an unfinished, missing and lost part of the history of 20th century. Behind the historical scenes that the First World and Third World weaved together, it was a historical structure and field of movements constituted by the coexistences and interrelations of colonialism and post-colonialism, and of the Cold War and the post-Cold War. As kinetic and potential energy of history, having undergone various transformations, envelopments, and substitutions, “Bandung”, “Asia-Africa-Latin America”, and the Third World are still the signal of our daily life and the foundation of realpolitik today; it is neither trivial nor abstract, but concretely grounded in between the contexts of our social reality: in between Bamako and Beirut, in between Kinshasa and Cairo, or even among Yiwu, Madrid, and Athens, or among Delhi, Mexico city, and Shanghai…

To rake up the historical discussion of Bandung and the Third World is not only to produce knowledge of the “Third World” in the complicated current structure-field, but, more importantly, to produce a new “Third World” through producing knowledge of alliance. Third World is not ready-made; rather, in the midst of rapid-changed international political and diplomatic game, it is like a public sphere, which might close at any time, and is growing while dying, so it requires indefinite recommencement and reinvention. For me, in this constant reinvention, there lies the possibility of change. And that is what I have referred to as “from the Third World to the Third Power” in my summary statement of the conference last year. In order to follow up the thinking last year and proceed the discussion, please allow me to make a revisit.

There is the first kind of power, which includes techne, capital and the financial and business empires that constitute the singular universality. Examples of which include WTO, Microsoft, Google, Facebook, the international system of intellectual property, etc. They disguise to be neutral, universal, and therefore they are genuinely borderless transnational powers; they support, dominate as well as dictate the perceptual experiences and aesthetic structure of our daily life.

This kind of power is the production of the restructuring of capitalism during the 1970s and the 1990s, which is also referred to as financial and information capitalism.

In the past forty years, the information economy, information capitalism and global social inequality, polarization and social exclusion have developed in a criss-crossed manner. Financial capitalism and information capitalism have created what Manuel Castells referred to as the “Fourth World”, which is no longer the Third World, and is not divided as “the South and the North” or “the East and the West”. The network of wealth, information and power has connected and realigned the world, and the geopolitics has been rearranged. The “Forth World” does not signify the exploited proletarians, for being exploited is viewed as a privilege, but the neglected, excluded people and society outside of the global network.

Today, the wealth-information-power network has constituted a totality of global policy, the form and theme of domination and oppression has changed, and become invisible. I mean, the wealth-information-power global network machinery becomes imperceptible. We are not struggling with some “kernel” external to us, and we are not even fighting against the bondage of some boundaries. The boundaries between companies such as Facebook, Google, and Alibaba and the society are no longer clear, as they are merging indefinitely with the society, and successfully posing under the guise of the society itself, so the global policy installation they have constructed does not have an exterior. Oppression and exploitation have hidden among and with us, become the everyday life that we are situated in and with enjoyment, and force us to struggle against our own mechanism of desire.

The second kind of power is the power of intellectual reflectivity produced by the intellectual community, that is to say, the insurmountable complex of critical thinking and social theories, especially those critical lefts gestated and born from the global social movements around 1968 motivated by the two events in Asia: the Cultural Revolution and the Vietnam War, which include the leftist discourses, knowledge, and movements all along the last fifty years.

Since the global financial crisis of 2008, there has been a wave of social movements in east Asia, and there is the so-called "Candle Light Movement" in South Korea. Some intellectuals might imagine uniting together these local struggles in order to create a common struggle or a struggle for “the common”. However, we can see, in the complicated historical relations and social dynamic mechanism, all of these social movements not only diverge in terms of their goals and their requests, but also conflict with each other. In my view, these social movements in recent years, however, are leading towards a renewed “ideologicalization” and even politicalization of everyday life. What those declarations in the name of “civilized society” or “civil society” have brought about are a unilateral political society, in which ethnics split, comrades fall out, and struggles happen frequently, and publicity seems open but actually frozen, the symptom of which is: it is diverse in forms but single in fact, it is common but not shared, and it is popular but not public.

In recent years, the crisis of the intellectual left, whose ideas are based on Western radical philosophy, has become increasingly apparent. No matter in Washington or New York, in Taiwan or Hong Kong, the intellectual lefts have lost their languages and reliance in the increasingly complex situation of the real politics. In the recent rounds of social movements in the left form but right fact, they have been easily incorporated and abandoned pitilessly. The intellectual left is useless in the real politics, because an empire is the left, center and right at the same time.

Then, what is the Third Power? Beyond the political operations of a nation state and beyond the conceptual operations of the academia and intellectual community, there is a much wider and more profound world of the popular thinking and popular life. This world is just where the “Third Power” might emerge from. Because this world is both complex and vulgar, it is yet to present in our knowledge and experience. For now, all that is represented is only the body of the people.

The "occupying" movements around the world at the beginning of the 21st century are completely different from the those around 1968. Those around 1968 were social movement of culture, and intellectuals' movement. However, the subject of the "occupying" movements in the new century are consisted of the popular excluded by the society, the nameless majority, and the popular mass sacrificed by the global network. They have no organization, and no plan, so although they have reached the end of their forbearance, they have no alternative direction and no idea of what to do. They are just like "boiling frogs", so they have no choice but an angry outburst, without any clear target. These are the masses in the “occupying” movements in the new century. Unlike their counterparts in the workers' movements in 19th or 20th century, or in the student movements of 1960s, they are “atomized” before the movements begin, and they cannot even be called as a collective. They come and gather in a street or in a square, just for a form of display, even if such display has made clear political / social consequences. For example, the color revolution of the so-called "Arab Spring" (it is worth noting that calling this movement a “revolution” just highlights the lack of our vocabulary!), was just an unintentional by-product. The meaning of such “gathering” was really nothing but for the sake of gather and to display, and the only important thing is to show: I am here, therefore I exist. It was as what the late Iranian film director Abbas Kiarostami had written in one of his poems: “non-East, non-West, non-South, non-North. I am here.”

However, in any case, the world that the popular present and live in is just the “Third World” that Mr. Paik Nak-chung has been insisting on for years. He states: when we speak of the “Third World”, we do not mean that we are attempting to divide the world into three parts. On the contrary, we are uniting the world which has been divided into different camps and different hierarchical levels into one, in terms of the idea of people’s life. To this end, we have to temporarily suspend existing discourses and knowledge and ground ourselves into the popular life and real experience of different worlds (whether it is the First World or the Third World). We have to connect ourselves to the popular life, the real sensibility and social consciousness in different regions to discover the new power of the unification of knowledge and practice, which is the new Third Power. It is this power that unites us today; it is this power that makes us realize new unification in the current reality; and it is this power that makes us set off from the site of popular life to re-define ourselves and others, freedom and equality, and justice and the future.

For sure, we are not able to call for the Third Power, not even able to describe it. But to "start out again" sixty years after the Bandung Conference provides us a new opportunity to break through many different “institutions” formed since 1950s, and to continue those unfinished missing history, which is the potential history of “the Third Power”. By such “breaking through” and “continuing” work, we could write a belated manifesto for the complex, contradicting and unpredictable 20th century in the process of the life history, social history, political history and intellectual history of the period longer than half a century.

2

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Cultural Revolution. Half a century ago, two events in Asia, the Cultural Revolution and the war in Vietnam, inspired the political as well as social imagination of the West, initiating a cultural, intellectual and political process since the 1968. However, in the context of the West, the effect of this clash developed into nothing but a series of new social movements "tinkering around". Those claims of liberation made in 1968 in the West actually survive well with neoliberalism through these social movements. (The Iniva’s claim of multiculturalism really epitomizes the failure of the Third World.) Here, there are many questions to be asked: why do the social movements since 1960s accept leftists but not socialism? Why does the social revolution claimed at that time become social works of kinds of NGOs? Why do these social movements avoid the most important issue of government system and instead seek to “put a patch on” the existing system? Why is the fighting social consciousness born out of 1968 so easily absorbed by the spectacle policy of capitalism after the Cold War?

I still remember the title of Jomo Kwame Sundaram’s speech on the Asian Circle of Thought in 2012, “Imperialism is Alive and Well, But Still Evolving”. I agree to the message of this title. After the long-term evolution of the 20th century, capitalism has been going through multiple generations and presented as a new and updated version of itself and its operation form: in short, from exploitation to deprivation, from oppression to substitution, from possession to domination.

Capitalism does not only represent an ideology and a domination, but a mode of life and knowledge. From software to hardware, from coding to governing, it dictates the daily life of people across different regions, and infiltrates through social organism and bio-politics, shaping our behavior habits and dream ways, desire structure and affect structure. In the past thirty years, capitalism has already evolved or transformed from an exploitation of our labor value by its mode of production to a deprivation of our dynamics on the bio-political level. Globalization of techne and transnational capitals together have constructed the global possession and domination, and the predicament of “global imprisonment, and local exile” is shared by every one of us. In this light, the so-called “liberation” is no long a freedom from imprisonment and domination or the usual anti-oppression and anti-control, because today there is no way to imagine a free world external of the current order of power. What David Harvey has termed as “the reproduction of space” of capital, or what Joseph Alois Schumpeter has termed as “creative destruction”, has already constructed a new domination, under which the territorial logic of power and the capitalist logic of power have been a perfect unity, and that is to say, imperialism and an empire coexist together.

Thus, the competition among states is no longer about the right of possession, but about the right of domination. The fundamental question of bio-politics is not one of oppression, but of substitution. From oppression to substitution, it means to replace and abolish your organs with artificial limbs: it is not that you get the artificial limbs for your deficiency, but on the contrary, it is the artificial limbs make you handicapped. I feel very strongly that contemporary art, craft art, many institutionalized knowledge and the academy institution itself are precisely the artificial limbs of politics, ethics, and aesthetics for us in our time.

The new domination of global capitalism is no longer operating through the logic of oppression and exploitation because the dictator has already been made invisible, and we fail to find a clear enemy to struggle against. In this new domination, what works is the logic of substitution in the politics of consumerism: you want a social revolution, but it is replaced by a social movement; you want socialism, but it is substituted into intellectual left; you want the freedom of life and development, but it is taken place of by the freedom in the free market; you want media freedom, but get the we-media; you call for the gathering and presence of the people, but get moments of circle of friends in social media; you are supposed to be a producer of culture, but become a consumer in a natural manner; you want to be a warrior, but end up of becoming an actor…

In this situation, how could the intellectual community and the art community work together to overcome the exploitation and substitution of this new domination? I do not believe in what Bernard Stiegler, the French philosopher, has stated: total proletarianization is a potential for liberation. We must learn to face the life experiences and fates of the multitudes in a real manner. Without exceptions, we are all bodies exhausted and substituted by the production and consumption of everyday life, and we are all individuals tamed and defeated by the trivialities of daily life. We must rediscover our feelings and intellects, rediscover the energy for sense, understanding and action, so as to regain the strength of expression and change ourselves. This urge us to invent a new historical-techne philosophy, a new political economy and a new bio-politics, and to develop a new learning of understanding and practice that connects the collective and the individuals, and opens our bodies to minds.

To establish the Bandung School is because of a series of observation and thinking during running the Inter-Asia School: we have entered the 21st century for already 16 years. From 9/11 to the “war on terror”, from sub-prime crisis to Occupying Wall Street, from the occupation movements such as the “sunflower” and the “umbrella” , right to left, to the "Arabic Spring", from Syria to Ukraine, from "indignados" to "nuit debout", from the refugee crisis to Brexit, from the Snowden event to Trump winning the election… through the series of events, I have a strong sense that new century is beginning to take shape, and the “prospect” of the new century has shown its initial symptoms, but we still lack a clear understanding of it. The social intermediary mechanism has been renewed, the mode of social domination and social movements has changed, so as the way in which the mass is congregated, the input and output of information, and the meaning of democracy, populism, and even the very idea of politics. The changes have already happened, and the power of the changes has already appeared. But, are we ready?

These are what I have been thinking about, and I am looking forward, through thinking and discussions among friends, and more importantly, through our long-term cooperation in the future, to thinking these changes, and to profoundly understanding the century laying foundation for itself. Based on these thinking, Kuan-hsing and I have given a very unconventional name to the new research institute: Another World Project: Bandung School. The tension between the reality of “Bandung” (or the opposite) and the fictions of “another world” (or the opposite) is the key to this name.

We hope, through this conference, to gather together our intellectual friends to share their intellectual movement experience, and their precious advices on the mission, problematics, organization and operation of the new research institute. I am looking forward to connecting the powers from both of our artistic and intellectual friends, so that to explore a piece of new field for our sensitivity in the multi-layered reality of “message-spectacle-capital”, and to make the “Bandung spirit” reinvented; to open a new strategic space for our creativity, let the “Third World” re-founded in the new reality, and let the flowers of an “Another World” blossom from it.

1

On January 18th 2006, the evening before the opening of the World Culture Forum (WCF), a crowd of intellectuals and activists gathered in the city of Bamako to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Bandung Conference. Since then, in the spirit of the Bandung Conference, the “Bamako Proposal” was delivered, the aim of which was to create a popular, pluralistic and multipolar historical subject, to transcend the opposition between the North and the South, to go beyond the rules and values of the capitalism and imperialism, and to construct “the common” from diversity.

The “Bamako Proposal” explicitly highlighted ten concrete themes: global political organizations, economic organizations of the world system, the future of agricultural societies, establishing a united front for working people, a mode of regionalization that served the interests of the people, an authentic social democracy, gender equality, environmental-friendly management of the Earth’s resources, a democratic administration for the media and cultural diversity, and the democratization of international organizations.

Ten years have passed. What has the situation become now?

During the WCF, Samir Amin and others already clearly remarked that the “Bandung Spirit” had inevitably been worn out. In those countries in the South, the governments willingly gave up social democratic process and settled with neoliberalism, the result of which was a return to the path of populism, or rendering a service to the imperialism, and, in both cases, democracy break faith with the people. In those countries in the North, the Left and the Right have already reached an agreement around economic liberalism, which is replacing social democracy with the American version of minimal democracy.

Last year, we have held the “Bandung/Third World 60 Years” Hangzhou Forum, and I have met many of those who are also seated among here today during that event. During my summary statement for that conference, I have especially pointed out that the old form of internationalism no long suffices; in fact, the symbol for international solidarity in the 19th century, the song l’internationale, is now only sung when one is in a state of drunken ecstasy. The “Bandung Spirit” has already been worn out by the production/consumption system of global capitalism; and the people, having been isolated by the conflicts of interest between nation states and by the international chain of supply and demand, have been transformed into competitors and enemies of each other. The people have been re-split under the dual structure of imperialism and nation state, broken and discretized in the entanglement of the history of colonialism and the Cold War, and distributed and integrated in the globalized network of production and consumption --- the fate of the people, in the words of the artist Chen Chieh-Jen, is in “global imprisonment, and local exile”.

In such predicament, we cannot help but to ask: in the new situation of the 21st century, what exactly is the ground and kernel of a new alliance and a new solidarity? Was it only the “development” and “win-win” figured out according to profit that could unite us?

Through the establishment of the Bandung School, we are intentionally raking up the past --- bringing up again “Asia-Africa-Latin America” and the Third World. We just must cling to it, for the history should not be let go easily. Because this project that has not been carried out yet but already announced a failure was an unfinished, missing and lost part of the history of 20th century. Behind the historical scenes that the First World and Third World weaved together, it was a historical structure and field of movements constituted by the coexistences and interrelations of colonialism and post-colonialism, and of the Cold War and the post-Cold War. As kinetic and potential energy of history, having undergone various transformations, envelopments, and substitutions, “Bandung”, “Asia-Africa-Latin America”, and the Third World are still the signal of our daily life and the foundation of realpolitik today; it is neither trivial nor abstract, but concretely grounded in between the contexts of our social reality: in between Bamako and Beirut, in between Kinshasa and Cairo, or even among Yiwu, Madrid, and Athens, or among Delhi, Mexico city, and Shanghai…

To rake up the historical discussion of Bandung and the Third World is not only to produce knowledge of the “Third World” in the complicated current structure-field, but, more importantly, to produce a new “Third World” through producing knowledge of alliance. Third World is not ready-made; rather, in the midst of rapid-changed international political and diplomatic game, it is like a public sphere, which might close at any time, and is growing while dying, so it requires indefinite recommencement and reinvention. For me, in this constant reinvention, there lies the possibility of change. And that is what I have referred to as “from the Third World to the Third Power” in my summary statement of the conference last year. In order to follow up the thinking last year and proceed the discussion, please allow me to make a revisit.

There is the first kind of power, which includes techne, capital and the financial and business empires that constitute the singular universality. Examples of which include WTO, Microsoft, Google, Facebook, the international system of intellectual property, etc. They disguise to be neutral, universal, and therefore they are genuinely borderless transnational powers; they support, dominate as well as dictate the perceptual experiences and aesthetic structure of our daily life.

This kind of power is the production of the restructuring of capitalism during the 1970s and the 1990s, which is also referred to as financial and information capitalism.

In the past forty years, the information economy, information capitalism and global social inequality, polarization and social exclusion have developed in a criss-crossed manner. Financial capitalism and information capitalism have created what Manuel Castells referred to as the “Fourth World”, which is no longer the Third World, and is not divided as “the South and the North” or “the East and the West”. The network of wealth, information and power has connected and realigned the world, and the geopolitics has been rearranged. The “Forth World” does not signify the exploited proletarians, for being exploited is viewed as a privilege, but the neglected, excluded people and society outside of the global network.

Today, the wealth-information-power network has constituted a totality of global policy, the form and theme of domination and oppression has changed, and become invisible. I mean, the wealth-information-power global network machinery becomes imperceptible. We are not struggling with some “kernel” external to us, and we are not even fighting against the bondage of some boundaries. The boundaries between companies such as Facebook, Google, and Alibaba and the society are no longer clear, as they are merging indefinitely with the society, and successfully posing under the guise of the society itself, so the global policy installation they have constructed does not have an exterior. Oppression and exploitation have hidden among and with us, become the everyday life that we are situated in and with enjoyment, and force us to struggle against our own mechanism of desire.

The second kind of power is the power of intellectual reflectivity produced by the intellectual community, that is to say, the insurmountable complex of critical thinking and social theories, especially those critical lefts gestated and born from the global social movements around 1968 motivated by the two events in Asia: the Cultural Revolution and the Vietnam War, which include the leftist discourses, knowledge, and movements all along the last fifty years.

Since the global financial crisis of 2008, there has been a wave of social movements in east Asia, and there is the so-called "Candle Light Movement" in South Korea. Some intellectuals might imagine uniting together these local struggles in order to create a common struggle or a struggle for “the common”. However, we can see, in the complicated historical relations and social dynamic mechanism, all of these social movements not only diverge in terms of their goals and their requests, but also conflict with each other. In my view, these social movements in recent years, however, are leading towards a renewed “ideologicalization” and even politicalization of everyday life. What those declarations in the name of “civilized society” or “civil society” have brought about are a unilateral political society, in which ethnics split, comrades fall out, and struggles happen frequently, and publicity seems open but actually frozen, the symptom of which is: it is diverse in forms but single in fact, it is common but not shared, and it is popular but not public.

In recent years, the crisis of the intellectual left, whose ideas are based on Western radical philosophy, has become increasingly apparent. No matter in Washington or New York, in Taiwan or Hong Kong, the intellectual lefts have lost their languages and reliance in the increasingly complex situation of the real politics. In the recent rounds of social movements in the left form but right fact, they have been easily incorporated and abandoned pitilessly. The intellectual left is useless in the real politics, because an empire is the left, center and right at the same time.

Then, what is the Third Power? Beyond the political operations of a nation state and beyond the conceptual operations of the academia and intellectual community, there is a much wider and more profound world of the popular thinking and popular life. This world is just where the “Third Power” might emerge from. Because this world is both complex and vulgar, it is yet to present in our knowledge and experience. For now, all that is represented is only the body of the people.

The "occupying" movements around the world at the beginning of the 21st century are completely different from the those around 1968. Those around 1968 were social movement of culture, and intellectuals' movement. However, the subject of the "occupying" movements in the new century are consisted of the popular excluded by the society, the nameless majority, and the popular mass sacrificed by the global network. They have no organization, and no plan, so although they have reached the end of their forbearance, they have no alternative direction and no idea of what to do. They are just like "boiling frogs", so they have no choice but an angry outburst, without any clear target. These are the masses in the “occupying” movements in the new century. Unlike their counterparts in the workers' movements in 19th or 20th century, or in the student movements of 1960s, they are “atomized” before the movements begin, and they cannot even be called as a collective. They come and gather in a street or in a square, just for a form of display, even if such display has made clear political / social consequences. For example, the color revolution of the so-called "Arab Spring" (it is worth noting that calling this movement a “revolution” just highlights the lack of our vocabulary!), was just an unintentional by-product. The meaning of such “gathering” was really nothing but for the sake of gather and to display, and the only important thing is to show: I am here, therefore I exist. It was as what the late Iranian film director Abbas Kiarostami had written in one of his poems: “non-East, non-West, non-South, non-North. I am here.”

However, in any case, the world that the popular present and live in is just the “Third World” that Mr. Paik Nak-chung has been insisting on for years. He states: when we speak of the “Third World”, we do not mean that we are attempting to divide the world into three parts. On the contrary, we are uniting the world which has been divided into different camps and different hierarchical levels into one, in terms of the idea of people’s life. To this end, we have to temporarily suspend existing discourses and knowledge and ground ourselves into the popular life and real experience of different worlds (whether it is the First World or the Third World). We have to connect ourselves to the popular life, the real sensibility and social consciousness in different regions to discover the new power of the unification of knowledge and practice, which is the new Third Power. It is this power that unites us today; it is this power that makes us realize new unification in the current reality; and it is this power that makes us set off from the site of popular life to re-define ourselves and others, freedom and equality, and justice and the future.

For sure, we are not able to call for the Third Power, not even able to describe it. But to "start out again" sixty years after the Bandung Conference provides us a new opportunity to break through many different “institutions” formed since 1950s, and to continue those unfinished missing history, which is the potential history of “the Third Power”. By such “breaking through” and “continuing” work, we could write a belated manifesto for the complex, contradicting and unpredictable 20th century in the process of the life history, social history, political history and intellectual history of the period longer than half a century.

2

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Cultural Revolution. Half a century ago, two events in Asia, the Cultural Revolution and the war in Vietnam, inspired the political as well as social imagination of the West, initiating a cultural, intellectual and political process since the 1968. However, in the context of the West, the effect of this clash developed into nothing but a series of new social movements "tinkering around". Those claims of liberation made in 1968 in the West actually survive well with neoliberalism through these social movements. (The Iniva’s claim of multiculturalism really epitomizes the failure of the Third World.) Here, there are many questions to be asked: why do the social movements since 1960s accept leftists but not socialism? Why does the social revolution claimed at that time become social works of kinds of NGOs? Why do these social movements avoid the most important issue of government system and instead seek to “put a patch on” the existing system? Why is the fighting social consciousness born out of 1968 so easily absorbed by the spectacle policy of capitalism after the Cold War?

I still remember the title of Jomo Kwame Sundaram’s speech on the Asian Circle of Thought in 2012, “Imperialism is Alive and Well, But Still Evolving”. I agree to the message of this title. After the long-term evolution of the 20th century, capitalism has been going through multiple generations and presented as a new and updated version of itself and its operation form: in short, from exploitation to deprivation, from oppression to substitution, from possession to domination.

Capitalism does not only represent an ideology and a domination, but a mode of life and knowledge. From software to hardware, from coding to governing, it dictates the daily life of people across different regions, and infiltrates through social organism and bio-politics, shaping our behavior habits and dream ways, desire structure and affect structure. In the past thirty years, capitalism has already evolved or transformed from an exploitation of our labor value by its mode of production to a deprivation of our dynamics on the bio-political level. Globalization of techne and transnational capitals together have constructed the global possession and domination, and the predicament of “global imprisonment, and local exile” is shared by every one of us. In this light, the so-called “liberation” is no long a freedom from imprisonment and domination or the usual anti-oppression and anti-control, because today there is no way to imagine a free world external of the current order of power. What David Harvey has termed as “the reproduction of space” of capital, or what Joseph Alois Schumpeter has termed as “creative destruction”, has already constructed a new domination, under which the territorial logic of power and the capitalist logic of power have been a perfect unity, and that is to say, imperialism and an empire coexist together.

Thus, the competition among states is no longer about the right of possession, but about the right of domination. The fundamental question of bio-politics is not one of oppression, but of substitution. From oppression to substitution, it means to replace and abolish your organs with artificial limbs: it is not that you get the artificial limbs for your deficiency, but on the contrary, it is the artificial limbs make you handicapped. I feel very strongly that contemporary art, craft art, many institutionalized knowledge and the academy institution itself are precisely the artificial limbs of politics, ethics, and aesthetics for us in our time.

The new domination of global capitalism is no longer operating through the logic of oppression and exploitation because the dictator has already been made invisible, and we fail to find a clear enemy to struggle against. In this new domination, what works is the logic of substitution in the politics of consumerism: you want a social revolution, but it is replaced by a social movement; you want socialism, but it is substituted into intellectual left; you want the freedom of life and development, but it is taken place of by the freedom in the free market; you want media freedom, but get the we-media; you call for the gathering and presence of the people, but get moments of circle of friends in social media; you are supposed to be a producer of culture, but become a consumer in a natural manner; you want to be a warrior, but end up of becoming an actor…

In this situation, how could the intellectual community and the art community work together to overcome the exploitation and substitution of this new domination? I do not believe in what Bernard Stiegler, the French philosopher, has stated: total proletarianization is a potential for liberation. We must learn to face the life experiences and fates of the multitudes in a real manner. Without exceptions, we are all bodies exhausted and substituted by the production and consumption of everyday life, and we are all individuals tamed and defeated by the trivialities of daily life. We must rediscover our feelings and intellects, rediscover the energy for sense, understanding and action, so as to regain the strength of expression and change ourselves. This urge us to invent a new historical-techne philosophy, a new political economy and a new bio-politics, and to develop a new learning of understanding and practice that connects the collective and the individuals, and opens our bodies to minds.

To establish the Bandung School is because of a series of observation and thinking during running the Inter-Asia School: we have entered the 21st century for already 16 years. From 9/11 to the “war on terror”, from sub-prime crisis to Occupying Wall Street, from the occupation movements such as the “sunflower” and the “umbrella” , right to left, to the "Arabic Spring", from Syria to Ukraine, from "indignados" to "nuit debout", from the refugee crisis to Brexit, from the Snowden event to Trump winning the election… through the series of events, I have a strong sense that new century is beginning to take shape, and the “prospect” of the new century has shown its initial symptoms, but we still lack a clear understanding of it. The social intermediary mechanism has been renewed, the mode of social domination and social movements has changed, so as the way in which the mass is congregated, the input and output of information, and the meaning of democracy, populism, and even the very idea of politics. The changes have already happened, and the power of the changes has already appeared. But, are we ready?

These are what I have been thinking about, and I am looking forward, through thinking and discussions among friends, and more importantly, through our long-term cooperation in the future, to thinking these changes, and to profoundly understanding the century laying foundation for itself. Based on these thinking, Kuan-hsing and I have given a very unconventional name to the new research institute: Another World Project: Bandung School. The tension between the reality of “Bandung” (or the opposite) and the fictions of “another world” (or the opposite) is the key to this name.

We hope, through this conference, to gather together our intellectual friends to share their intellectual movement experience, and their precious advices on the mission, problematics, organization and operation of the new research institute. I am looking forward to connecting the powers from both of our artistic and intellectual friends, so that to explore a piece of new field for our sensitivity in the multi-layered reality of “message-spectacle-capital”, and to make the “Bandung spirit” reinvented; to open a new strategic space for our creativity, let the “Third World” re-founded in the new reality, and let the flowers of an “Another World” blossom from it.