2010

This article was originally a lecture presented by the author at the China Academy of Art in December, 2010, published with consent of the author.

I. Specter of the Machine

When image production has become excessive due to the rapid advancement of digital technology, with digital images proliferating, it is actually difficult to regard photography as a standalone subject in this Web 2.0 era, where social network engineering dominates. Isolated from the infiltrations of other image production mechanisms within the digital field, the quality of the hybrid images may well be regarded as a common characteristic of all floating entities within the digital space at this moment. Given the distinctiveness of such characteristic, it is evident that previous discussions surrounding photography (or simulated images, gelatin silver images, etc.) must undergo revision, or even be discarded, in order to re-examine and analyze the current state of images. However, these changes are still ongoing, and amid the turbulent waves of changes, how can we maintain a stable perspective on imagery without being trapped in biased interpretations? First and foremost, it is necessary to clarify a few points in a dialectical approach: Have the characteristics of hybrid images fundamentally altered the nature of photographic imagery? Has the ontological position of the photographer and the viewer been interchanged or displaced? Does the variation of ethical relationships in the digital field dictate the foundational ethical values governing the mechanisms of photographic image production?

In the 1990s, shortly after the establishment of the World Wide Web, email and hypertext became the main forms of exchange in the digital network. At that time, hyperlinks had not yet matured, and computers were regarded as just another platform for the knowledge economy. The dominant technological and instrumental mindset prevented a vast majority of intellectuals from paying attention to, analyzing, and theorizing about new cultural phenomena and public spheres. Lack of, as well as late appearance of, related discourse indicated the mainstream's resistance and rejection of new things. In his book Dark Fiber: Tracking Critical Internet Culture[1], Geert Lovink extensively describes the cultural emptiness that characterized the dawn of the digital age.

Lovink attempts to construct a critical theory of the emerging digital network culture, disentangling it from the technocratic and commercially oriented discourses as well as the grand discourses of post-structuralism, deconstructivism, and postmodernism that emerged in France in the 1960s. From a modern-day perspective, his macro assumptions remain deeply trapped in the bias of temporality, that is, the computer-as-hypertextual-site mentality that dominated Lovink’s imagined reality of the future cyberworld:

Internet was not about losing one's body in an immersive environment. Its potential to network was real, not virtual. The net was not a simulator for this or that experience. If it appealed to a sexual desire, it must have been one based on code, not on images—distributed, abstract delusion, not a (photo)graphic illusion. [2]

Internet is real, not virtual; social networks have realized this inference, in some cases allowing reality and virtual networks to merge and integrate. However, such argument—which emphasizes the primacy of code, holding that code governs or dominates the generation of network desires, rejecting images and photography and viewing them as mere accessories to network—clearly conflicts with the phenomenon that numerous image-based network communities such as YouTube and Flickr are increasingly emerging nowadays. This example leads to some interesting topics: Why are images, particularly photographic images, regarded as negative elements of network, a certain dark side, or in the author's words, a kind of “dark fiber,” a negative being that is prepared but left unused? Do the rejection of images and the expansion of the dominance of linguistic code indicate a peculiar polarity between texts and images or videos at the dawn of digital culture? Rejecting images also means rejecting the allure and charm of images; does it suggest the existence of a certain indescribable specter of digital rationality?

By placing Lovink's dismissal of the role of images in the digital network within the historical context of technological and computer development, it is found that this perspective responded to the special historical relationship between the unperceived screens (of computers and other digital devices) and digital computing devices, as well as the contradictory historical nature of screens. As the mechanism of producing digital images and space for viewing them, the screens of computers and digital devices would inevitably be shaped by this historical quality, which in turn determined the nature of digital images.

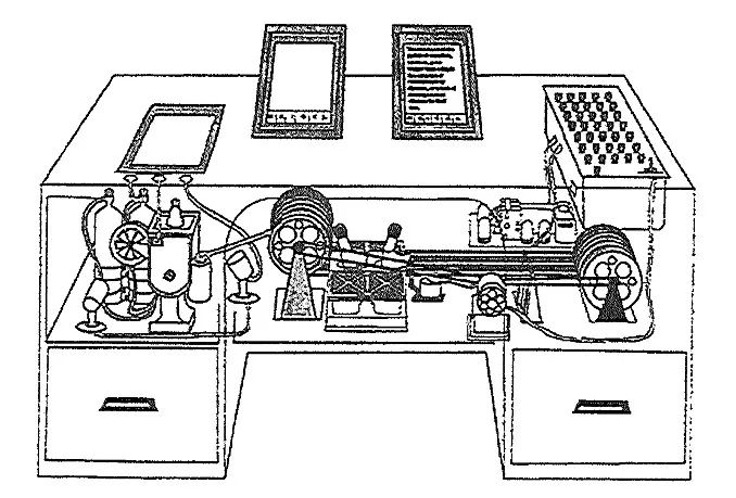

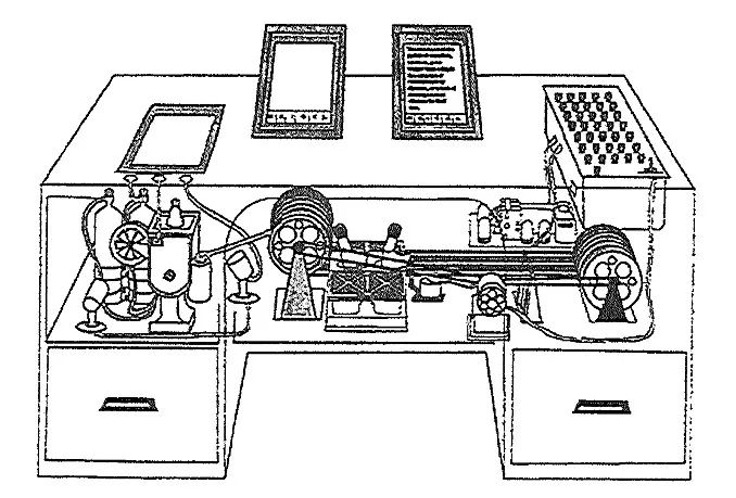

The early prototype of computer architecture (Memex, 1945) was merely a theoretical concept that was never actually realized: a workstation equipped with two slanting translucent screens, a photographic copying plate, and a keyboard. These gadgets combined would be used to manipulate and access the information recorded on microfilm beneath the desk (Figure 1):

Memex was originally proposed as a desk at which the user could sit, equipped with two slanting translucent screens upon which material would be projected for convenient reading. There was a keyboard to the right of these screens, and a set of buttons and levers which could be used to search information. If the user wished to consult a certain article, “he [tapped] its code on the keyboard, and the title page of the book promptly appear[ed]” (Bush 1945: 103). The images were stored on microfilm inside the desk, […] a photographic copying plate was also provided on the desk. […] The user could classify material as it came in front of him using a stylus, and register links between different pieces of information using this stylus. [3]

Figure 1. Memex Design Sketch

The two screens in the design sketch—or more precisely, two “silver screens” with images projected from behind the screens—showed the projected data images stored on the microfilm. The user's viewing experience developed from the optical observations of various projection devices that existed before the invention of the film in the 19th century. This represents a simulated relationship among image materials, where the order of film and photographic optical substances governs the exchange of imagination in the knowledge-viewing process, from searching and accessing to copying.

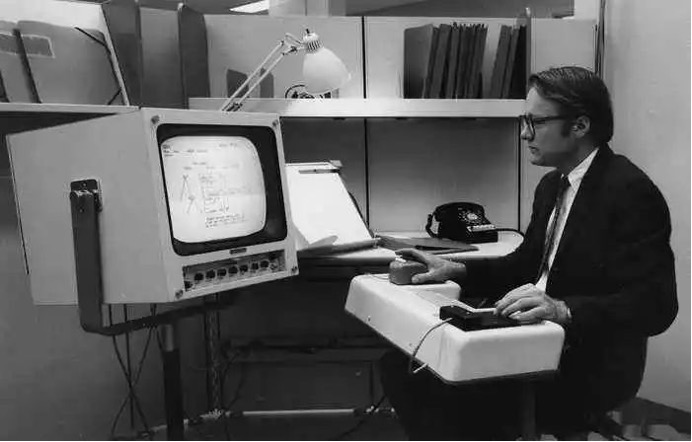

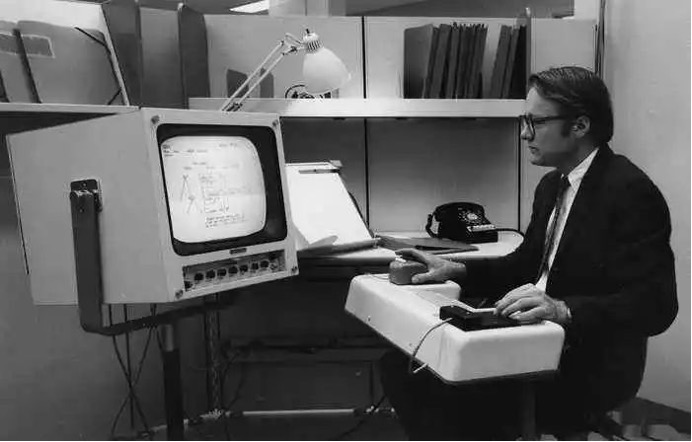

Memex was essentially an imaginary technological product of a transitional period when analog optics started to enter the digital information space. The non-purity of Memex as a hybrid limited the possibility of it being studied and put into practice in an era marked by longings for stability and unity and fears of chaos and uncertainty. Strangely, Memex appeared as a philosophical toy, an optical device for popular entertainment of the 19th-century Industrial Revolution, as well as an imaginary product of post-industrial digital information technology. Perhaps due to this non-purity in its onto-epistemological significance, or the limitations of the digital imaging technology at that time, Douglas Engelbart was only able to produce the first operational prototype (1968) more than twenty years after Vannevar Bush proposed the vision of Memex (1945), which incorporated the screen of Memex and the mouse invented by Engelbart himself. [4] (Figure 2) In Engelbart's interview (1968), he mentioned that his initial inspiration for computing devices was the idea of sitting in front of a giant screen where various symbols would appear, and by manipulating those symbols, people could make the computer operate. He particularly emphasized the importance of transforming information through a punch card machine or a computer printer into an array of symbols that could be presented on the screen.

Engelbart learned screen technology from the radar detection techniques he acquired while serving in the Navy during World War II. The controlling of the radar screen and direct manipulation of the screen image through buttons later became the inspiration for his invention of the mouse, which marked the beginning of human-computer interface. For Engelbart, images were inseparable from the computer mindset and operation, yet this view was not accepted by the mainstream computing technology community at that time:

Engelbart's revision of the dream would prove to be too radical for the engineering community, however. The idea that a screen might be attached to a computer, and that humans might interact with information displayed on this screen, was seen as ridiculous. [5]

The engineers' resistance continued until the mid-1970s, when the core operations of hypertext could be smoothly executed on these computer devices. This is a surprising historical fact, considering that we now view screens as essential for all digital devices; the iPad even conceals all the basic components for computer operations behind the screen, leaving only the screen itself. Instead of being rejected, this phenomenon has become a trend. From being a rejected accessory during the early period of the information revolution to today's new network generation, where cyberspace has evolved from a digital space into another kind of social space, the screen has reversed its role to become a representative device and site that dominates various digital (human-computer, cyber, social) interfaces. Such qualitative reversal of the role of the screen in the course of digital history is undoubtedly a result of multiple complex cultural and social factors, and cannot be simply explained through the reductionism of technological history.

Simply imagining the moment in 1968 when the first electronic computing device with a screen—the prototype of the computer—appeared is enough to spark deep thoughts. It was a tumultuous time, a watershed where protest movements in Western society reached a peak, and social culture was filled with skepticism and extreme ideologies, accompanied by relentless sharp, head-on conflicts. Reason, order, and power became the common enemies in these conflicts. Be it left-wing or right-wing, new or old, discourses and practices of all ideologies were being fragmented; the anxiety, insecurity, and euphoria that accompanied reconstruction and mobility, eschatological redemption, and utopia were the popular topics at that time. In the absence of a clear subject, the information technology revolution took place in such a unique historical moment and cultural atmosphere. Engelbart initially hoped to invent a computing device that could control the unpredictable and changeable; his thought, to a certain extent, corresponded to Foucault's archeological discourse on “episteme.” Calculation, exchange, classification, and value were the shared elements of Engelbart's and Foucault's concepts, which represented how the spirit of the times were carried out respectively in the fields of technology and the humanities. If this hypothesis holds, it is safe to say that the first computer screen played the role of the “specter of the machine,” an unconscious mirror of computer technology, a disturbing dark place.

Figure 2. The Mother of All Demos, Douglas Engelbart, 1968

Jonathan Crary, in the first chapter “Modernity and the Problem of the Observer” of his book Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity (1990), explicitly articulated with great surprise and concern his unease about the rapid proliferation of the emerging computer imagery. More visual virtual spaces were being created, transitioning from analog images to digital electronic images. Image technology was increasingly governing and controlling the field of vision, diminishing the dominance of the observer and the eye and undermining the subjectivity of the regulator between information networks and rationality. In the midst of the critical transformation in the nature of visuality, Crary posed a vital question, one that we are currently exploring:

What is the relation between the dematerialized digital imagery of the present and the so-called age of mechanical reproduction? [6]

In the course of history, how were continuity and rupture manifested in the two imageries of fundamentally different natures, thereby influencing the changes in the forms of visuality? Basically, Crary believes in the continuity between images, asserting that there is no fundamental difference between digital images and analog images—only differences in form and production technology, at most. The old modes of viewing will continue to operate within the new image field. The new digital images will extend and deepen the viewing experience of the 19th-century “society of the spectacle,” making it more complex and comprehensive.

Maintaining this continuous historical perspective in the examination of vision and image technology as well as their radical change from analog to digital, Crary continues his focus on the field of vision production in the 19th century in his next book Suspension of Perception, but slightly later in timeline, and explores the topic of “attention.” He insists putting “cultural forms” before “content differences,” holding that the visual activities and viewing experience offered by television and the personal computer follow the 19th-century viewing mechanisms characterized by spectacle, only with a deeper and more comprehensive approach to regulate viewers' looking and attention to create an illusion of interactivity. But in fact, the viewers are immobilized, partitioned, and isolated, thus losing their agency and freedom. [7]

Crary has also pointed out in some passages that the differences in the nature of images can affect the viewing mechanisms, and that each type of optical devices has their own historical developments. According to Crary, these images and optical devices must be treated differently, and it is important “not to minimize the need for analyzing specific and local interfaces of humans and machines.” [8] Nevertheless, Crary still maintains an undifferentiating view; for him, from the 19th century to the end of the 20th century, with either analog or digital images, there was only one type of screen used as a mechanism to discipline and regulate the observer:

Attentive behavior in front of all kinds of screens is increasingly part of a continuous process of feedback and adjustment within what Foucault calls a “network of permanent observation.” [9]

If Crary's feelings about the emerging digital visual culture in Techniques of the Observer can be regarded as pessimistic, then Suspension of Perception adopts the same pessimism regarding the rise of cyberculture at the end of the last century; he even made a grim prediction that the cyberworld of the 21st century would exacerbate the spectacle looking that had been ongoing since the late 19th century, managing and controlling the mechanisms of looking, disciplining spectators, and stripping away their autonomy. As a result, what little had remained of the time pieces at the end of the 19th century that once allowed for a little gray-zone freedom—where one could briefly drift off or daydream—would completely disappear:

But at the end of the twentieth century, the loosely connected machinic network for electronic work, communication, and consumption has not only demolished what little had remained of the distinction between leisure and labor but has come, in large arenas of Western social life, to determine how temporality is inhabited. Information and telematic systems simulate the possibility of meanderings and drift, but in fact they constitute modes of sedentarization, of separation in which the reception of stimuli and the standardization of response produce an unprecedented mixture of diffuse attentiveness and quasi-automatism, which can be maintained for remarkably long periods of time. In these technological environments, it's questionable whether it is even meaningful to distinguish between conscious attention to one's actions and mechanical autoregulated patterns. [10]

The cyberworld standardizes and regulates attention through viewing mechanisms to constitute the paramount “digital and cybernetic imperatives.” [11] A fully digitized cyberworld will be one that defies reflection and completely interiorizes the observing subject, while the screen will become the final interface where the subject disappears.

II. The Imaginary Signifier

Crary's biopolitical argument focuses on the concentration and diffusion of attention of the perceptual experience, which constitutes the basis of his examination of the different optical devices of the 19th century. Visual research discourses and painting space construct how these devices dissolved the observing subject amidst the decline of its (innate) comprehensive capabilities. Crary's extensive positivist visual archaeology seeks to construct a unified discourse; thus, it suspends or simplifies the complexity and diversity of the topic, overlooking the fundamental specificities and differences between silver screens of the late 19th century, television screens, and computer screens. To highlight such differences, it is evident that the analytical focus must be shifted away from biopolitics, that is, extend beyond the narrow scope of perception to encompass the interaction between perception and other forms of visual consciousness. This relates to Metz's analysis of the decisive mechanism of the “imaginary signifier” (le signifiant imaginaire) in the process of generating “the impression of reality” (l'impression de réalité) while watching a film. The optical experience of watching films is not solely built on physiological and psychological perceptual cognition, or solely on the stimulus (the film):

This is because the impression of reality results partly from the physical (perceptual) nature of the cinematic signifier: images obtained by photographic means and therefore particularly ‘faithful’ in their function as effigies, presence of sound and movement that are already a bit more than effigies since their ‘reproduction’ on the screen is as rich in sensory features as their production outside a film, etc. […] However, I remarked also that the similarity of the stimuli does not explain everything, since what characterises, and even defines, the impression of reality is that it works to the benefit of the imaginary and not of the material which represents it (that is, precisely, the stimulus). […] Consequently, the impression of reality cannot be studied simply by comparing it with perception but we must also relate it to the various kinds of fictional perceptions, the chief of which, apart from the representational arts, are the dream and the phantasy. [12]

Metz rigorously defines and analyzes the impression of reality of films, which broadly refers to all that is related to the viewing of films, whether they are narrative or non-narrative. The impression of reality associated with a film depends on the signifying perception (perceptis du signifiant), which include both the common perception and fictional perception mentioned above. And the fiction-effect, which is unique to narrative films, brings the spectator's consciousness into a mixture of the dream, the daydream, and real perception.

Regardless of the type of film, the impression of reality determines the credibility of films to the audience. Based on Metz's theory, it is clear that the silver screen experiences of the late 19th century involve extremely different imaginary signifiers than the optical experiences with the television screen and the computer screen as well as operational experiences with the latter. This significant difference arises, on one hand, from the different natures of the images on the screens (the stimuli) and the sites where the screening activity takes place; on the other hand, the difference stems from the spectator's own intentionality, the desire to watch, which determines the vectorial change of the perceptual consciousness within the “impression of reality–fiction effect–real effect” triangle. Of course, there are also complex factors including cultural and social institutional determinants as well as political and economic effects, which cannot be simply explained as the ultimate goal of power control.

In the late 19th century, with the advent of stereoscopic photography, Praxinoscope à Projection, Théâtre-Optique[13] and various optical illusion devices that used visual illusion to create phantasmagoric effects, the conflict between illusion and reality of films was adjusted comprehensively and produced a new signifying perception. This new approach no longer wholly relied on the psychological effects of physiological perception. The impression of reality offered by films replaced the previous desire for phantasmagoric images, leaving a divided silver screen between the optical experience and the real experience, waiting for the spectator to reconstruct the pseudo-three-dimensionality of stereoscopic photography. The spatial dislocation of the Praxinoscope reflected floating ghostly illusions, dissociating images from space, creating a non-spatial floating effect. Films stitched these dislocated and detached screens into a single screen, merging the pseudo-reality of space and phantasmagoric images into the screen image as well as the fiction and reality effects outside the screen. The dark space of the immense architecture, the spectator's distance from the screen, and the disproportionately large screen and images compared to the real world (people and objects appeared too large, and the city and nature—the external world—seemed too small) could all manipulate the credibility of films under the impression of the reality, real perception, and fiction effect, thereby reducing the alert judgment of perception and consciousness.

The visual experience provided by television screens brought the human-machine interface back to a pre-cinematic mode associated with the optical devices of the 19th century. It compressed images into an indoor furniture-style box. However, unlike the extreme proximity to image devices before, the television screen was positioned at a certain distance from the viewer, neither as far as the cinematic experience, nor as close as the 19th-century optical devices required. Such a viewing distance is similar to one between a painting and its spectators. Watching television is part of everyday life; more importantly, this indicates that television is an indispensable part of life and does not require a special, isolated space to operate and produce various viewing effects. Its imaginary signifier does not require a suspension or interruption of general perceptual experience as a prerequisite for viewing, and the viewer is alert in the visual experience of watching television, yet with diffused and centrifugal attention almost identical to daydreaming; in contrast, with the film screen, the viewer is induced to lower their alertness through the original setting, maintaining focus while wandering on the blurred boundaries of sleep, dreams, and daydreams. To produce the impression of reality, the television screen must be lit up and turned on; otherwise, it is just an opaque black glass screen. For pre-cinematic optical devices, the silver screen and the image can be regarded as a combination of separate elements, similar to a container and its contents, and the image contents can be rewritten or repossessed. For the film screen, its projected images are temporary, non-repetitive and cannot be possessed (before the emergence of re-recording technology). For the television screen, its image contents are virtual, with the imaginary signifier creating the reality effect, which is not the impression of reality; such effect depends on a specific temporality: simultaneity. Thus, television particularly emphasizes presence and immediacy, and the visual experience of watching television is similar to spotting, witnessing, and peeking. This quality features and connects many complex types of so-called “television programs” and “screen content.” Besides simultaneity, these visual contents also possess other special temporal qualities—momentariness and temporariness. Non-continuity seems to have become a significant difference between television and cinema or the pre-cinematic optical devices of the 19th century.

Since the emergence of the first generation of personal computers, computer screens have become a part of everyday life. Unlike earlier computing technologies, which were used by only a small group within the tech community, it is now common for households to have multiple screens. Due to the similarities with televisions in appearance, material and technical functionality, computer screens are often mistakenly assumed to offer the same viewing experience as TV screens. However, when we consider the nature of the images displayed and the relationship between the screen and its controlling systems, it becomes clear that computer screens operate under a fundamentally different human-machine interface compared to television or cinema screens. Computer screen images are no longer primarily serving the purpose of narrative or fiction; in other words, the standards for judging the credibility of realism and real-world effects no longer hold validity here. If we consider that the earliest personal computer screens fostered a viewing tendency inclined towards cognitive learning behaviors, the viewer’s conscious awareness was more heightened compared to the semi-conscious, dreamlike state typical of watching television or films. Focused computer screen viewing requires certain bodily actions from the observer—such as tactile engagement and hand movements. Clearly, in this interactive state with the viewer’s body, the image can be altered. From these aspects, it can be said that the mental state evoked by film and television viewing is vastly different from that experienced with computer screen use. This difference, to borrow Metz’s terminology, does not lie in the materiality of the image or in general perception, but arises from a new relationship between the image and the human-machine interface. Initially characterized by a simple mechanical relationship (as in stereoscopic photography), this interface is effectively eliminated (or rendered invisible) in cinema, while in television, it is acknowledged but suspended, functioning as a single-purpose tool for reception (much like a radio or refrigerator).

The computer screen embodies this new human-machine interface, functioning in a way that demands a novel realm of the imaginary signifier and a new field of imagination between viewing and the viewer. Undoubtedly, with the rapid development of computer technology, the computer is no longer confined to isolated personal use. The ability to operate hypertext and manage multiple windows on the screen has long become an essential feature. As the World Wide Web evolved into the second generation (Web 2.0), social media and social networks also developed. Computers initially transitioned from being primarily tools for information communication to becoming multifunctional hypermedia. Today, they have further transformed into social and community media, even being referred to as post-media. In a short period, the computer screen—originally characterized by low narrativity and low fictionality—underwent significant changes. It became intermingled with other types of interfaces, creating more virtual interface spaces and crafting a more complex maze of human-computer interactions. The focus of viewing behavior during the personal computer era no longer applies to this new interface maze. The rapid flow of searches, the disorderly and ruleless jumping and weaving through virtual spaces, and navigation without a map—these demands on screen and image mechanisms can no longer be satisfied by the single frame and linear, single-point viewing experience of the virtual perspective space found in film and television screens. The mixture of different types of images makes it impossible for viewing cognition to operate continuously within a single field, and may even disrupt or interrupt that cognition. So how can we say that the computer screens of the new internet era are the same as film or television screens, without any differences? The computer screens of the new internet era have not only changed in terms of form, technology, and material aspects (for example, Apple's iPad has integrated the last remaining physical keyboard into the screen itself), but this transformation reflects more than just an aesthetic (industrial design) significance. Beneath the minimalist aesthetic lies another imaginary signifier driven by the supreme demand of the viewing mechanism: the need to render all devices and mechanisms that obstruct or are irrelevant to viewing—those mechanical, technological, and operational components—completely invisible and transparent. The user is left with only the screen, facing a single screen. The new screen viewing experience is one of free-form fractals, chaos, and fluid drifting across multiple spaces—a viewing experience marked by uncertainty. The English words “browser” and “browsing” inherently carry the meaning of wandering and roaming. The instability of the viewing experience hints at the instability of both images and interfaces, which may stem from their fragmentation or the constantly evolving virtual and network interfaces.

The above analysis and comparison primarily revolve around the perceptual-cognitive relationship between the viewer and the (silver) screen, as well as the related differences and changes in the imaginary signifier that emerge from it.

On the cultural level of society and economy, the differences among the three (silver) screens and their visual content become more evident and direct. Films and television have commodified leisure culture through economic production, creating brief engagement for the public through entertainment and fictional narratives, thereby facilitating the exchange process between labor and virtual reproduction. Participants, in an automatic or semi-automatic manner, passively receive everything presented by the screen images, engaging and receiving without the need to learn potentially more complex operations. Metz's concept of “lessened wakefulness” refers to a mental state that drifts between dreams, daydreams, and reality, representing the suspension or cancellation of subjectivity—whether temporarily or for an extended period. This state also involves the operation of secondary economic exchanges (psychic economy and monetary economy), which are not purely aimed at satisfying libidinal desires for pleasure. As commonly understood by general theories, the viewing experience in the gray zone of consciousness is a repetition of previous labor’s working through—a process of reworking the death drive and aggression inherent in labor, as well as the contradictory markers of active participation or passive reception within the unconscious field of secondary economic exchanges. This involves the libidinal economy. From this perspective, it becomes clear that regression during film viewing is necessary for the realization of aggression, with the active/passive positions constantly shifting and relocating in the darkness, meaning the viewer is not a consistently passive entity. The attitude of television viewers, apart from differing in degree, actually mirrors the unconscious processes of film viewers in the dark. It involves a metonymic (métonymie) substitution for metaphor (métaphore), where the constantly shifting bodily behavior of television viewers in the illuminated room is displaced (déplacer) by the condensed (condenser)and compressed unconscious drive work in the darkened cinema.

In short, the socio-economic significance of the cinema screen and the television screen lies in their use of different mirror-image rhetoric to continue the work of labor within the so-called virtual field of leisure and entertainment, reworking psychic economy for reproduction. The two types of symbols and signifiers—through fiction, hallucination, and narrative—are not for the sake of representing the desire for representation but rather to accelerate regression and the gray zone of semi-consciousness to facilitate the exchange of drives and the working through of labor. This is the true intention. Film and television audiences are not consistently passive entities; the active/passive shifts of the viewing subject occur in a continuous process of regression. The gray zone of consciousness accompanying the act of viewing is a gradually dissolving yet constantly reconstituting and unstable subject. Subject and subjectivity do not completely retreat or disappear but are instead torn apart and mended in the pursuit of (silver) screen images, responding to the (silver) screen’s call beyond a distant, dark unconsciousness.

III. Frozen Sharing

The computer screen, unlike the cinema or television screen, forms an inseparable unity with electronic devices, physical materials (commonly referred to as hardware), and control command codes (commonly referred to as software). The computer screen is an extended surface of the computer, serving as its skin and face. The relationship between the cinema screen and the projector, or between the television screen and its transistors and electronic components, is separated and distinct. However, for the viewer, the (silver) screen is everything—they do not notice the existence of the projector behind it or the components inside the television box. There is only the (silver) screen and the images. In contrast, the viewer of a computer screen cannot view the screen and the images in isolation, nor can the screen be separated from the other components of the computer. From the moment the screen is touched or turned on, the viewer/user has already entered the interior of the computer, interacting through an abstract language with the hardware. As a product of the commodity economy, the computer’s circulation and transaction do not lie in leisure, entertainment, or labor exchange. The computer was invented and created by a special social class—the technological elite—for the purpose of knowledge production, serving as a new tool and material for knowledge-based economic production. Operating and using a computer requires a certain level of learning and prior knowledge, similar to the mechanical craftsmen of the 19th century. Before facing the screen, the user must learn an entire set of basic languages to operate the computer, to interact with the screen, to view, and to face the screen. Only by assuming the position of a knowledgeable subject can the user effectively view and operate the computer. The default determining conditions of the human-computer interface involve a shift in the epistemological position and learning how to view mirrored images. From the earliest days of mainframe computers, where small screens could only crudely display operational codes and numbers (even before clear images were possible, the screen already served as a communication interface), to the era of personal computers, where screens could clearly present images, the computer has gradually evolved from an information work platform to a communication medium. The role of computers has since continued to evolve, extending beyond just being a medium and moving toward even more diverse forms of functionality.

The relationship between computer users and screen images is one of direct engagement and two-way interaction, which differs from the indirect, one-way viewing of film and television audiences, who passively receive images through the screen. Naturally, different types of viewing experiences lead to the emergence of different imaginative mechanisms. Film and television, through the nature of visual media and the viewing environment (especially in the case of cinema), lower the audience’s awareness and resistance, thereby enhancing credibility. In contrast, the unique epistemological relationship between computer screens and users, characterized by a highly conscious form of viewing, projects an imaginative mechanism that transcends the conventional principles of realism, effectively breaking through the demands imposed by the “reality effect.”Outside the domain of images and their referential fields, the demand for the accuracy of images in the lifeworld recedes. The realm of the computer viewer/user is one where images and their nominal responses dominate, immersing the viewer in a world constructed by the processes of knowledge production and reproduction. Beyond this realm, the interface between the highly conscious viewer/user and the nominal digital image field (real and virtual) differentiates the relationship between the computer screen and reality. The film screen, in contrast, is isolated from the real world, projecting a constructed fictional world based on impressions of reality, like a conditional proposition of reality that operates under the premise of “as if.”The television screen has become integrated into the real world and everyday social life. Without the need for temporary displacement or isolation, it provides a distanced simultaneity and an in-the-moment witnessing of reality, offering a hyper-real third-person referential framework and a propositional world that asks, “What is this?” On the other hand, the images on the computer screen, originating from a nominal abstract logical nature, project another world that coexists in parallel with the real world. These images are not bound by the constraints of authenticity required by the real world. Instead, their determining conditions and driving forces stem from various human-computer interaction interfaces. This image world represents an extension of multiple (or even infinite) possible worlds, which may intersect and overlap with the real world, or may exist in parallel without ever intersecting. In the overlapping and converging worlds, multiple propositions operate, including paradoxes of “yes and no”and deeper contradictions inherent in the binary logic of computer mechanisms. These propositions simultaneously represent “as if” but also both “fact”and“counter-fact.”This contradictory nature gives rise to the unique symbiotic relationship between personal computers and fictionality. Fictionality does not come from an external addition, but rather from the demands of the real world, similar to cinema or television. It is the rational, unconscious hypertextual interaction of the computer screen and the human-computer interface—a form of computer game rather than a tool or product of commodified economic mechanisms. It is an intrinsic derivative of the computer itself. Marie-Laure Ryan analyzed how, when operating fictional worlds in the digital age through games, the mechanism of imagination suspends disbelief to facilitate judgments of authenticity, thereby creating a paradox:

Digital media have made important contributions to both immersion and self-reflexivity: whereas computer games absorb players for hours at a time into richly designed imaginary worlds, hypertext fiction explodes these worlds into textual shards, code poetry promotes awareness of the machine language that brings text the screen, and what Noah Wardrip-Fruin (2006) calls “process-intensive” works direct attention away from the surface of the screen, toward the virtuoso programming that generates the text. [14]

The perception of viewing a computer screen depends on the nature of the screen’s visual content. According to Metz’s analysis, the perception of film viewing primarily depends on the viewer’s imaginative mechanism. However, the representational material itself is not the main determining factor, which also refutes Crary’s argument that cultural forms dictate perception and behavior by controlling attention. Similarly, the act of viewing computer screen images, which also requires intense focus, has significantly different, even opposing effects on the viewing subject depending on whether the content is a game or text. One diminishes (or cancels) subjectivity, while the other, in contrast, enhances self-reflection.

Marie-Laure Ryan did not delve deeply into why such contradictory phenomena arise, leaving aside the issue of viewing computer-based texts and focusing solely on the analysis of immersive imaginative fiction in games. Regarding the reading of digital texts, Johanna Drucker compared the reading behaviors of medieval manuscripts and e-books using a pragmatic cognitive model, particularly addressing how hypertext on computer screens affects the position of the viewing subject. She found that both forms emphasize the interactive participation between the reader and the book:

The e-space of the page arises as a virtual program, interactive, dialogic, dynamic in the fullest sense. [15]

The images and written texts in medieval manuscripts interact in a way that resembles invisible writing and paratexts, much like the interconnections between hypertexts. Similarly, the exchanges between different virtual electronic spaces on the internet link “identity and activity” to form a new intersubjective community, increasing the surplus value of knowledge production as it circulates within both social spaces and digital-electronic spaces. Drucker’s pragmatic approach emphasizes the active agency of the subject when viewing/reading the hypertext of e-books. Bertrand Gervais, however, does not regard the dematerialized digital text and hypertext reading as an entirely new linguistic act. Therefore, he believes it cannot be explained using conventional pragmatic linguistic frameworks. He argues that the textual language appearing on screens goes beyond the narration of natural language. Hypertext, with its nonlinear automatic connections, is a “non-linear text composed of nodes connected together by hyperlinks. It is not just written, it is imbedded, a HTML code. The electrified text flows in any direction it wants, establishing links independently from its user.” [16]

The complexity and the overwhelming surge of textual information create difficulties and barriers to reading digital texts. This dual challenge leads to resistance and repetitive cognitive learning on the part of the reader/viewer. This may help explain the aforementioned point: the leaps in hypertext and code poetry interrupt the reader/viewer’s identification with the screen image, causing them to detach from the surface of the screen—or more precisely, to penetrate the screen’s thin layer and enter the ghostly realm of the controlling program behind it. The difference between the viewing/reading mode of hypertext on a computer screen and the reading of a printed book is precisely stored in this contrast. Christian Vandendorpe, borrowing from Heyer, distinguishes three modes of reading behavior: grazing, browsing, and hunting. Grazing refers to the act of continuous, long-duration reading of classic works. Browsing is the basic form of screen reading, while hunting involves using search engines, with the default goal of obtaining information through screen reading.[17] These two modes of screen reading are also common forms of screen viewing behavior. In the digital age, the readability and visibility of screens are almost homogeneous and indistinguishable. [18]

The emergence of email and web blogs accelerated the transformation of single-device electronic book page reading into a new form of network reading-writing interaction—screen reading-viewing-writing. The virtual space of the internet permeates the lifeworld, giving rise to new types of social spaces. In terms of the ubiquity and searchability of knowledge and information, the aspect of sharability transforms the screen within the online space into a completely redefined, multi-material, polyphonic, unperceived virtual social space, overproduced by multiple writers/readers/viewers. Even before the formation of social networks, online interactions had already encouraged people to upload or download more files and information due to the usage of new search engines, leading to:

The more information there is on the web, the more probability there is that a user will get an elaborate answer to any given request. That, in turn, provides a greater incentive for people to put documents on the web, knowing that it may be found by someone looking for it. [19]

“He knew that sooner or later, someone would see this data,”Clay Shirky refers to such files and data, hidden in the corners of websites and often overlooked, as“frozen sharing.” With the advent of social media, the meaning and vitality of sharing have been fundamentally transformed, leading to:

Sharing a photo by making it available online constitutes sharing even if no one ever looks at it. This “frozen sharing” creates great potential value. Enormous databases of images, text, videos, and so on include many items that have never been looked at or read, but it costs little to keep those things available, and they may be useful to one person, years in the future. [20]

Social media expands the scope and temporality of sharing, making it no longer necessary for the giver and the receiver to know each other. Therefore, sharing photos on social media does not require the assumption of a pre-existing social relationship. Furthermore, personal photos (or other file data) are no longer excluded from the public domain due to amateur or professional aesthetic standards. Their value, which Clay Shirky refers to as derived surplus (or excessive) cognitive value, may increase from the unknown and may be re-created into communal value through sharing. Thus, sharing is unfrozen, and sharing is revitalized.

The temporality of photos will also shift due to the re-creation by social media, moving away from the original virtual space of the internet and into a new social space, projecting into a peculiar future. This strange temporal difference makes the almost conventional past-oriented nature of photos suddenly less certain. Similar manipulations of photographic images to alter temporality also appeared in the 19th century, in the strategies used by museums and art galleries for reproducing and managing artworks through photography:

[…]Less reproduced art is less significant. The unphotographed, unpublished work of art exists in a kind of limbo. In fact, under the aura of the post-photographic museum, the unphotographed work can hardly be said to exist at all. In post-photographic art history, discovering and publishing such a work is almost a second act of creation. [21]

Perhaps such a parallel comparison lacks deeper significance, as social media and art galleries ultimately belong to two completely different social and cultural domains. The comparison is simply intended to highlight that the temporality of photography as a reproduction and as a shared object on social media can both be reshaped and modified. In the digital network era, temporality, along with space, has indeed been shattered into scattered, fragmented, non-spatial forms. Michel Serres, in his book Atlas, vividly describes the drastic changes in temporality within today’s society, permeated by digital and electronic media:

[…]virtual space does not maintain the same relationship with time as the space of the physical world[…] In fact, it can negotiate, against time, an analysis that partially destroys the obligation of simultaneity by desynchronizing transmission and reception, for example. I can hear tomorrow what you tell me yesterday, or see tonight images that were broadcast long ago. […]virtual space is a space-time, except that I can establish some countercurrents within the irreversibility of duration. [22]

The computer screen has evolved from the desktop personal computers to the networked era of social media, and its essential meaning has shifted from the mechanisms of knowledge economy production to ethical relationships. The non-linear, non-temporal nature eliminates both synchronicity and its precedence — the temporal qualities of film and television screens — giving rise to a new social space built upon the core domain of knowledge space. This social space is entirely different from the fleeting social collectives created by film through fiction and narrative, and it is also distinct from the isolated and solitary social monads that witness distant events through television.

Social media, or rather social media networks and social network engineering, claim that communal values precede knowledge, commodities, and other values; the categorical imperative of ethical principles seems to predetermine the meaning of both the content and form of screen images. Is this a false proposition, a new digital illusion, a utopia that is in fact nihilistic, masking a larger system of social control (such as the central server system of cloud computing, which some open software activists refer to as an evil plan or network governance)? The virtual space of social networks continuously infiltrates the real world—such as in many socio-political movements, or the human flesh search unique to the East—digital images are no longer simply the enchanting inhabitants of screens. These image ghosts drift everywhere, seeking physical entities to possess, traversing the fragmented social groups—simultaneously virtual and symbiotic, sharing or plundering the vast contents of one grand millennium Alexandria library after another, or even seizing dominion. Can the communal values of goodness, friendship, trust, and freedom, which are extolled by ethics and religion, truly serve as measures for the new virtual and real social spaces? The screen, the ubiquitous screen and its images—do the flickering lights represent illumination or a faint phosphorescence in the darkness of the night?

[1] Lovink, Geert. Dark Fiber: Tracking Critical Internet Culture, M.I.T. Press, 2002, pp. 4, 30-41.

[2] Ibid., p.79.

[3] Barnet, Belinda, and Darren Tofts. “Too Dimension: Literary and Technical Images of Potentiality in the History of Hypertext.” A Companion to Digital Literary Studies, eds. Ray Simens and Susan Schreibman, Blackwell Publishing, 2007, p. 286.

[4] Regarding the history of computer technology development, from 1940 to 1960, various technological devices of different sizes emerged during this period. Wikipedia's article on computers lists numerous important computing and calculating tools from various technological perspectives. Engelbart's innovations would not be possible without these preceding technological advancements. Most of the gigantic computing tools mentioned in Wikipedia receive emphasis on their technical aspects; that is, from a technocratic perspective, the focus is limited to the expansion of technological rational power based on material cultural practices, where computational capacity and work efficiency are often the criteria for assessing the effectiveness of new computing tools. Under the economic effects of rational politics, we naturally do not see discourses on aesthetic matters and ethical relationships related to computers and calculator technology that go beyond the material existence. Dictated by such mindset, the screen is excluded from the discourses on computing tools. Despite the fact that the invention and use of the mouse are inseparable from the screen, the screen is still alienated, left unaddressed. Thus, when we search for the article on screens in Wikipedia, we encounter the same technologicalism, only to find an utter technical manual explaining what computer (television, digital) screens are.

[5] Barnet, Belinda, and Darren Tofts. “Too Dimension: Literary and Technical Images of Potentiality in the History of Hypertext.” A Companion to Digital Literary Studies, eds. Ray Simens and Susan Schreibman, Blackwell Publishing, 2007, p. 289.

[6] Crary, Jonathan. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity, M.I.T. Press, 1990, p. 2.

[7] Crary, Jonathan. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity, M.I.T. Press, 1990, pp. 74-75. Spectacle is not primarily concerned with a looking at images but rather with the construction of conditions that individuate, immobilize, and separate subjects, even within a world in which mobility and circulation are ubiquitous. […] This is why it is not inappropriate to conflate seemingly different optical or technological objects: they are similarly about arrangements of bodies in space, techniques of isolation, cellularization, and above all separation. Spectacle is not an optics of power but an architecture. Television and the personal computer, even as they are now converging toward a single machinic functioning, are antinomadic procedures that fix and striate. They are methods for the management of attention that use partitioning and sedentarization, rendering bodies controllable and useful simultaneously, even as they simulate the illusion of choices and “interactivity.”

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., p. 76.

[10] Ibid., pp. 77-78.

[11] Ibid., p. 148.

[12] Metz, Christian. The Imaginary Signifier: Psychoanalysis and Cinema. Translated by Celia Britton, Annwyl Williams, Ben Brewster, and Alfred Guzzetti, Indiana University Press, 1982, p. 140.

[13] Crary, Jonathan. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity, M.I.T. Press, 1990, pp. 259-267.

[14] Marie-Laure Ryan, “Fictional Worlds in the Digital Age,” A Companion to Digital Literary Studies, eds. Ray Siemens and Susan Schreibman, Blackwell Publishing, 2007, p. 250.

[15] Johanna Drucker, “The Virtual Codex from Page Space to E-space,” A Companion to Digital Literary Studies, eds. Ray Siemens and Susan Schreibman, Blackwell Publishing, 2007, p.221, 225, 229.

[16] Bertrand Gervais, “Is There a Text on This Screen Reading in an Era of Hypertextuality,” A Companion to Digital Literary Studies, eds. Ray Siemens and Susan Schreibman, Blackwell Publishing, 2007, p. 194.

[17] Christian Vandendorpe, “Reading on Screen: The New Media Sphere,” A Companion to Digital Literary Studies, eds. Ray Siemens and Susan Schreibman, Blackwell Publishing, 2007, pp. 204-205.

[18] The computer processes digitized text as images, displaying it on the screen, making it difficult to distinguish between text, images, and visuals in a digital environment. Additionally, hypertext and text connections are constructed and conceptualized spatially. Vandendorpe emphasizes that the hyperlinked web further highlights the tension between visual dominance on the page and textual logic. For reference, see footnote 17, pp.206-207, p.211, as well as Matthew G. Kirschenbaum, “The Word as Image in an Age of Digital Reproduction,” in Eloquent Images: Word and Image in the Age of New Media, eds. Mary E. Hocks and Michelle R. Kendrick, M.I.T Press, 2003.

[19] Same as footnote 17, p.206.

[20] Clay Shirky, Cognitive Surplus, Penguin Books, 2010, p. 174.

[21] Peter Walsh, “Rise and Fall of the Post-Photographic Museum: Technology and the Transformation of Art,” Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage: A Critical Discourse, eds. Fiona Cameron and Sarah Kenderdine, M.I.T Press, 2007, p. 30.

[22] “l'espace virtuel n'entretient pas les mêmes relations avec le temps que l'espace du monde... il peut, en effet, négocier, à contre temps, une analyse qui détruit en partie l'obligation de simultanéité, en désynchronisant l'émission et la réception, par exemple. Je puis entendre demain ce que tu me dis hier ou voir ce soir des images émises jadis. [...]l'espace virtuel est un espace-temps, à ceci près que je puis établir quelques contre-courants dans l'irréversibilité de la durée. ” Michel Serres, Atlas, Flammarion, 1996, pp. 189-190.

Translated by Jeffrey Wu & Du Ruoyu

This article was originally a lecture presented by the author at the China Academy of Art in December, 2010, published with consent of the author.

I. Specter of the Machine

When image production has become excessive due to the rapid advancement of digital technology, with digital images proliferating, it is actually difficult to regard photography as a standalone subject in this Web 2.0 era, where social network engineering dominates. Isolated from the infiltrations of other image production mechanisms within the digital field, the quality of the hybrid images may well be regarded as a common characteristic of all floating entities within the digital space at this moment. Given the distinctiveness of such characteristic, it is evident that previous discussions surrounding photography (or simulated images, gelatin silver images, etc.) must undergo revision, or even be discarded, in order to re-examine and analyze the current state of images. However, these changes are still ongoing, and amid the turbulent waves of changes, how can we maintain a stable perspective on imagery without being trapped in biased interpretations? First and foremost, it is necessary to clarify a few points in a dialectical approach: Have the characteristics of hybrid images fundamentally altered the nature of photographic imagery? Has the ontological position of the photographer and the viewer been interchanged or displaced? Does the variation of ethical relationships in the digital field dictate the foundational ethical values governing the mechanisms of photographic image production?

In the 1990s, shortly after the establishment of the World Wide Web, email and hypertext became the main forms of exchange in the digital network. At that time, hyperlinks had not yet matured, and computers were regarded as just another platform for the knowledge economy. The dominant technological and instrumental mindset prevented a vast majority of intellectuals from paying attention to, analyzing, and theorizing about new cultural phenomena and public spheres. Lack of, as well as late appearance of, related discourse indicated the mainstream's resistance and rejection of new things. In his book Dark Fiber: Tracking Critical Internet Culture[1], Geert Lovink extensively describes the cultural emptiness that characterized the dawn of the digital age.

Lovink attempts to construct a critical theory of the emerging digital network culture, disentangling it from the technocratic and commercially oriented discourses as well as the grand discourses of post-structuralism, deconstructivism, and postmodernism that emerged in France in the 1960s. From a modern-day perspective, his macro assumptions remain deeply trapped in the bias of temporality, that is, the computer-as-hypertextual-site mentality that dominated Lovink’s imagined reality of the future cyberworld:

Internet was not about losing one's body in an immersive environment. Its potential to network was real, not virtual. The net was not a simulator for this or that experience. If it appealed to a sexual desire, it must have been one based on code, not on images—distributed, abstract delusion, not a (photo)graphic illusion. [2]

Internet is real, not virtual; social networks have realized this inference, in some cases allowing reality and virtual networks to merge and integrate. However, such argument—which emphasizes the primacy of code, holding that code governs or dominates the generation of network desires, rejecting images and photography and viewing them as mere accessories to network—clearly conflicts with the phenomenon that numerous image-based network communities such as YouTube and Flickr are increasingly emerging nowadays. This example leads to some interesting topics: Why are images, particularly photographic images, regarded as negative elements of network, a certain dark side, or in the author's words, a kind of “dark fiber,” a negative being that is prepared but left unused? Do the rejection of images and the expansion of the dominance of linguistic code indicate a peculiar polarity between texts and images or videos at the dawn of digital culture? Rejecting images also means rejecting the allure and charm of images; does it suggest the existence of a certain indescribable specter of digital rationality?

By placing Lovink's dismissal of the role of images in the digital network within the historical context of technological and computer development, it is found that this perspective responded to the special historical relationship between the unperceived screens (of computers and other digital devices) and digital computing devices, as well as the contradictory historical nature of screens. As the mechanism of producing digital images and space for viewing them, the screens of computers and digital devices would inevitably be shaped by this historical quality, which in turn determined the nature of digital images.

The early prototype of computer architecture (Memex, 1945) was merely a theoretical concept that was never actually realized: a workstation equipped with two slanting translucent screens, a photographic copying plate, and a keyboard. These gadgets combined would be used to manipulate and access the information recorded on microfilm beneath the desk (Figure 1):

Memex was originally proposed as a desk at which the user could sit, equipped with two slanting translucent screens upon which material would be projected for convenient reading. There was a keyboard to the right of these screens, and a set of buttons and levers which could be used to search information. If the user wished to consult a certain article, “he [tapped] its code on the keyboard, and the title page of the book promptly appear[ed]” (Bush 1945: 103). The images were stored on microfilm inside the desk, […] a photographic copying plate was also provided on the desk. […] The user could classify material as it came in front of him using a stylus, and register links between different pieces of information using this stylus. [3]

Figure 1. Memex Design Sketch

The two screens in the design sketch—or more precisely, two “silver screens” with images projected from behind the screens—showed the projected data images stored on the microfilm. The user's viewing experience developed from the optical observations of various projection devices that existed before the invention of the film in the 19th century. This represents a simulated relationship among image materials, where the order of film and photographic optical substances governs the exchange of imagination in the knowledge-viewing process, from searching and accessing to copying.

Memex was essentially an imaginary technological product of a transitional period when analog optics started to enter the digital information space. The non-purity of Memex as a hybrid limited the possibility of it being studied and put into practice in an era marked by longings for stability and unity and fears of chaos and uncertainty. Strangely, Memex appeared as a philosophical toy, an optical device for popular entertainment of the 19th-century Industrial Revolution, as well as an imaginary product of post-industrial digital information technology. Perhaps due to this non-purity in its onto-epistemological significance, or the limitations of the digital imaging technology at that time, Douglas Engelbart was only able to produce the first operational prototype (1968) more than twenty years after Vannevar Bush proposed the vision of Memex (1945), which incorporated the screen of Memex and the mouse invented by Engelbart himself. [4] (Figure 2) In Engelbart's interview (1968), he mentioned that his initial inspiration for computing devices was the idea of sitting in front of a giant screen where various symbols would appear, and by manipulating those symbols, people could make the computer operate. He particularly emphasized the importance of transforming information through a punch card machine or a computer printer into an array of symbols that could be presented on the screen.

Engelbart learned screen technology from the radar detection techniques he acquired while serving in the Navy during World War II. The controlling of the radar screen and direct manipulation of the screen image through buttons later became the inspiration for his invention of the mouse, which marked the beginning of human-computer interface. For Engelbart, images were inseparable from the computer mindset and operation, yet this view was not accepted by the mainstream computing technology community at that time:

Engelbart's revision of the dream would prove to be too radical for the engineering community, however. The idea that a screen might be attached to a computer, and that humans might interact with information displayed on this screen, was seen as ridiculous. [5]

The engineers' resistance continued until the mid-1970s, when the core operations of hypertext could be smoothly executed on these computer devices. This is a surprising historical fact, considering that we now view screens as essential for all digital devices; the iPad even conceals all the basic components for computer operations behind the screen, leaving only the screen itself. Instead of being rejected, this phenomenon has become a trend. From being a rejected accessory during the early period of the information revolution to today's new network generation, where cyberspace has evolved from a digital space into another kind of social space, the screen has reversed its role to become a representative device and site that dominates various digital (human-computer, cyber, social) interfaces. Such qualitative reversal of the role of the screen in the course of digital history is undoubtedly a result of multiple complex cultural and social factors, and cannot be simply explained through the reductionism of technological history.

Simply imagining the moment in 1968 when the first electronic computing device with a screen—the prototype of the computer—appeared is enough to spark deep thoughts. It was a tumultuous time, a watershed where protest movements in Western society reached a peak, and social culture was filled with skepticism and extreme ideologies, accompanied by relentless sharp, head-on conflicts. Reason, order, and power became the common enemies in these conflicts. Be it left-wing or right-wing, new or old, discourses and practices of all ideologies were being fragmented; the anxiety, insecurity, and euphoria that accompanied reconstruction and mobility, eschatological redemption, and utopia were the popular topics at that time. In the absence of a clear subject, the information technology revolution took place in such a unique historical moment and cultural atmosphere. Engelbart initially hoped to invent a computing device that could control the unpredictable and changeable; his thought, to a certain extent, corresponded to Foucault's archeological discourse on “episteme.” Calculation, exchange, classification, and value were the shared elements of Engelbart's and Foucault's concepts, which represented how the spirit of the times were carried out respectively in the fields of technology and the humanities. If this hypothesis holds, it is safe to say that the first computer screen played the role of the “specter of the machine,” an unconscious mirror of computer technology, a disturbing dark place.

Figure 2. The Mother of All Demos, Douglas Engelbart, 1968

Jonathan Crary, in the first chapter “Modernity and the Problem of the Observer” of his book Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity (1990), explicitly articulated with great surprise and concern his unease about the rapid proliferation of the emerging computer imagery. More visual virtual spaces were being created, transitioning from analog images to digital electronic images. Image technology was increasingly governing and controlling the field of vision, diminishing the dominance of the observer and the eye and undermining the subjectivity of the regulator between information networks and rationality. In the midst of the critical transformation in the nature of visuality, Crary posed a vital question, one that we are currently exploring:

What is the relation between the dematerialized digital imagery of the present and the so-called age of mechanical reproduction? [6]

In the course of history, how were continuity and rupture manifested in the two imageries of fundamentally different natures, thereby influencing the changes in the forms of visuality? Basically, Crary believes in the continuity between images, asserting that there is no fundamental difference between digital images and analog images—only differences in form and production technology, at most. The old modes of viewing will continue to operate within the new image field. The new digital images will extend and deepen the viewing experience of the 19th-century “society of the spectacle,” making it more complex and comprehensive.

Maintaining this continuous historical perspective in the examination of vision and image technology as well as their radical change from analog to digital, Crary continues his focus on the field of vision production in the 19th century in his next book Suspension of Perception, but slightly later in timeline, and explores the topic of “attention.” He insists putting “cultural forms” before “content differences,” holding that the visual activities and viewing experience offered by television and the personal computer follow the 19th-century viewing mechanisms characterized by spectacle, only with a deeper and more comprehensive approach to regulate viewers' looking and attention to create an illusion of interactivity. But in fact, the viewers are immobilized, partitioned, and isolated, thus losing their agency and freedom. [7]

Crary has also pointed out in some passages that the differences in the nature of images can affect the viewing mechanisms, and that each type of optical devices has their own historical developments. According to Crary, these images and optical devices must be treated differently, and it is important “not to minimize the need for analyzing specific and local interfaces of humans and machines.” [8] Nevertheless, Crary still maintains an undifferentiating view; for him, from the 19th century to the end of the 20th century, with either analog or digital images, there was only one type of screen used as a mechanism to discipline and regulate the observer:

Attentive behavior in front of all kinds of screens is increasingly part of a continuous process of feedback and adjustment within what Foucault calls a “network of permanent observation.” [9]

If Crary's feelings about the emerging digital visual culture in Techniques of the Observer can be regarded as pessimistic, then Suspension of Perception adopts the same pessimism regarding the rise of cyberculture at the end of the last century; he even made a grim prediction that the cyberworld of the 21st century would exacerbate the spectacle looking that had been ongoing since the late 19th century, managing and controlling the mechanisms of looking, disciplining spectators, and stripping away their autonomy. As a result, what little had remained of the time pieces at the end of the 19th century that once allowed for a little gray-zone freedom—where one could briefly drift off or daydream—would completely disappear:

But at the end of the twentieth century, the loosely connected machinic network for electronic work, communication, and consumption has not only demolished what little had remained of the distinction between leisure and labor but has come, in large arenas of Western social life, to determine how temporality is inhabited. Information and telematic systems simulate the possibility of meanderings and drift, but in fact they constitute modes of sedentarization, of separation in which the reception of stimuli and the standardization of response produce an unprecedented mixture of diffuse attentiveness and quasi-automatism, which can be maintained for remarkably long periods of time. In these technological environments, it's questionable whether it is even meaningful to distinguish between conscious attention to one's actions and mechanical autoregulated patterns. [10]

The cyberworld standardizes and regulates attention through viewing mechanisms to constitute the paramount “digital and cybernetic imperatives.” [11] A fully digitized cyberworld will be one that defies reflection and completely interiorizes the observing subject, while the screen will become the final interface where the subject disappears.

II. The Imaginary Signifier

Crary's biopolitical argument focuses on the concentration and diffusion of attention of the perceptual experience, which constitutes the basis of his examination of the different optical devices of the 19th century. Visual research discourses and painting space construct how these devices dissolved the observing subject amidst the decline of its (innate) comprehensive capabilities. Crary's extensive positivist visual archaeology seeks to construct a unified discourse; thus, it suspends or simplifies the complexity and diversity of the topic, overlooking the fundamental specificities and differences between silver screens of the late 19th century, television screens, and computer screens. To highlight such differences, it is evident that the analytical focus must be shifted away from biopolitics, that is, extend beyond the narrow scope of perception to encompass the interaction between perception and other forms of visual consciousness. This relates to Metz's analysis of the decisive mechanism of the “imaginary signifier” (le signifiant imaginaire) in the process of generating “the impression of reality” (l'impression de réalité) while watching a film. The optical experience of watching films is not solely built on physiological and psychological perceptual cognition, or solely on the stimulus (the film):

This is because the impression of reality results partly from the physical (perceptual) nature of the cinematic signifier: images obtained by photographic means and therefore particularly ‘faithful’ in their function as effigies, presence of sound and movement that are already a bit more than effigies since their ‘reproduction’ on the screen is as rich in sensory features as their production outside a film, etc. […] However, I remarked also that the similarity of the stimuli does not explain everything, since what characterises, and even defines, the impression of reality is that it works to the benefit of the imaginary and not of the material which represents it (that is, precisely, the stimulus). […] Consequently, the impression of reality cannot be studied simply by comparing it with perception but we must also relate it to the various kinds of fictional perceptions, the chief of which, apart from the representational arts, are the dream and the phantasy. [12]

Metz rigorously defines and analyzes the impression of reality of films, which broadly refers to all that is related to the viewing of films, whether they are narrative or non-narrative. The impression of reality associated with a film depends on the signifying perception (perceptis du signifiant), which include both the common perception and fictional perception mentioned above. And the fiction-effect, which is unique to narrative films, brings the spectator's consciousness into a mixture of the dream, the daydream, and real perception.

Regardless of the type of film, the impression of reality determines the credibility of films to the audience. Based on Metz's theory, it is clear that the silver screen experiences of the late 19th century involve extremely different imaginary signifiers than the optical experiences with the television screen and the computer screen as well as operational experiences with the latter. This significant difference arises, on one hand, from the different natures of the images on the screens (the stimuli) and the sites where the screening activity takes place; on the other hand, the difference stems from the spectator's own intentionality, the desire to watch, which determines the vectorial change of the perceptual consciousness within the “impression of reality–fiction effect–real effect” triangle. Of course, there are also complex factors including cultural and social institutional determinants as well as political and economic effects, which cannot be simply explained as the ultimate goal of power control.

In the late 19th century, with the advent of stereoscopic photography, Praxinoscope à Projection, Théâtre-Optique[13] and various optical illusion devices that used visual illusion to create phantasmagoric effects, the conflict between illusion and reality of films was adjusted comprehensively and produced a new signifying perception. This new approach no longer wholly relied on the psychological effects of physiological perception. The impression of reality offered by films replaced the previous desire for phantasmagoric images, leaving a divided silver screen between the optical experience and the real experience, waiting for the spectator to reconstruct the pseudo-three-dimensionality of stereoscopic photography. The spatial dislocation of the Praxinoscope reflected floating ghostly illusions, dissociating images from space, creating a non-spatial floating effect. Films stitched these dislocated and detached screens into a single screen, merging the pseudo-reality of space and phantasmagoric images into the screen image as well as the fiction and reality effects outside the screen. The dark space of the immense architecture, the spectator's distance from the screen, and the disproportionately large screen and images compared to the real world (people and objects appeared too large, and the city and nature—the external world—seemed too small) could all manipulate the credibility of films under the impression of the reality, real perception, and fiction effect, thereby reducing the alert judgment of perception and consciousness.