2013

This article was originally written as a speech titled “History as ‘Diagnosis’” on February 5, 2013, when I accepted the invitation of Chen Chieh-jen and TheCube Project Space to give a talk at the “Forum on the Eve of Demolition” at the Happiness Building in Shulin District. I would like to thank my friends Chen Chieh-jen, Wang Mo Lin, Manray Hsu, Hou Shur-tzy, Hsieh Ying-chun, and Wang Jiahao for their valuable comments during the discussion. This paper has been edited by the author into a thesis format.

The only reason why art critic John Berger, even though he lives in seclusion in a rural village under the Alps and happily rides a heavy motorcycle, still wields his pen to write books is that he remains hopeful that visual world (art) can still serve as a critique of the real world, as he says: “I will judge the value of a piece of work according to whether it can help people to proclaim their social rights in the modern world. I hold to that.”[1] As a critic, Berger does not need to explain the relationship between artistic production and social rights, because art critics produce art externally, connecting the work to society through their own perspectives. Yet he leaves us with unanswered questions: what is the knowledge of artistic practice? What are social rights? Whose social rights? Can reflecting on social rights be a criterion for the knowledge of artistic practice? How does this differ from “literature as a vehicle for carrying the Dao”(文以载道) and the aestheticization of politics?

John Berg also reminds us that we cannot be moved by aesthetic emotion alone and beg the question about the relationship between art and nature, and between art and the world.

Art does not imitate nature, it imitates a creation, sometimes to propose an alternative world, sometimes simply to amplify, to confirm, to make social the brief hope offered by nature. Through the delicate white bird made of pine wood, which is often hung in almost every farmhouse in Eastern Europe, he asks us, “The white wooden bird is wafted by the warm air rising from the stove in the kitchen where the neighbours are drinking. Outside, in minus 25°C, the real birds are freezing to death!” It seems to suggest that this is the heart of the artistic practice: the two roles of visual world (art) in “replacing” or “confirming” the world.

In order to answer these two roles of art, and its relation to social rights, it is necessary to answer, first of all, where does our knowledge of artistic practice come from? How is it constructed and transmitted? Contemporary art theory has been subjugated to the philosophers' powerful pen, and aesthetic is carried out solely through their eyes, while the knowledge of artistic practice seems to be reduced to technology, those technical tools that we teach undergraduates, or marketing and management know-how. Worse still, artistic or aesthetic theories are not inspired by the artists' philosophies, but rather by the curators' mediation of various contemporary philosophical and social trends, or by the global biennial's need for “social turn” and “novelty”, and the knowledge of artistic practice is produced by teachers who speculate the market direction and maintain the mechanism of the academy. The knowledge of art theory and art practice involves different epistemologies (rather than the difference between epistemology and methodology). It is the difference between “What is art?” and “What should art be?” This paper examines the history of the production of subjectivity in Western art, and then [......] maps how the foundation of “What should art be” is shaped by the knowledge of historical social processes, so that there may be an opportunity to respond to the question of “What art can be”.

This paper attempts to prove a hypothesis with practical implications: “the knowledge of artistic practice is inseparable from the knowledge of socio-political processes”, and proposes an initial proposal of “Societal art”. Since I started teaching at the Art Academy, I have been thinking about what is the knowledge of artistic practice? Is it the principles, skills and tools of plastic arts? Is it aesthetics, philosophy, cultural theory or fieldwork, social research, participation? Is it cultural activism? Or is it really just life experiences? “Interdisciplinarity” is all the rage right now, but what knowledge of ‘inter-disciplinary’ artistic practice actually means is vague. In any case, aesthetics or artistic production is always subordinate to some kind of identity system, some kind of visibility, possibilities, and opportunities for dissemination and sharing. In Taiwan, the excellent students of top-notch academies have access to more alternative, leftist art theories, and have been nurturing the perennial winners of the big gallery and exhibition prizes. So, what does it mean to be politically radical and successful in the aesthetic marketplace? To understand this meaning, we must do two things with the discourse of artistic practice: re-historicize it and spatialize it. The purpose of historicizing and spatializing artistic production is to point out that no matter how reluctant we are to admit it, art, as a content with a particular form, is always closer to the objects of our disdain than we think. In Taiwan, art theory rarely confronts the dramatically changing spatio-temporal conditions of art's existence.

I. Art and Society: The Construction of Subjectivity in Western Modern Art

In his book The Rules of Art, Pierre Bourdieu cites Le Don des morts, written in 1991 by the famous French novelist Danièle Sallenave:

‘Shall we allow the social sciences to reduce literary experience – the most exalted that man may have, along with love – to surveys about our leisure activities, when it concerns the very meaning of our life?’[2]

Social scientists seem to be murderers of the aesthetic emotion, which is why the art world has always rejected social scientists as analysts, feeling that the aesthetic emotion and the inspiration to create are lost, that the work and the movement are “interpreted out”, and that the necessity to relate creative intentions to the social context deprives them of their autonomy. Arnold Hauser, an important left-wing sociologist of art, published his The Sociology of Art in German in 1974, which was translated into English in 1982. He once wrote:

“What remains beyond all doubt is that we can imagine a society without art but not art without society. ”[3] For him, art has to be seen in the context of social structure and history. While art is certainly a product of society, and artistic creation is subject to the class ideology of the established rulers, art also has the potential to respond to, criticize, and challenge the practices of established social institutions. The work of art is a dialectical structure, not just a form of content, not just a receiving “you” and a transmitting “I”, but a dialog developed through continuous interaction between the author and the viewer, a relational system of reciprocal references. Thus, society as a product of art is possible. I would like to begin my discussion with these two different perspectives.

1. Artistic Subjectivity

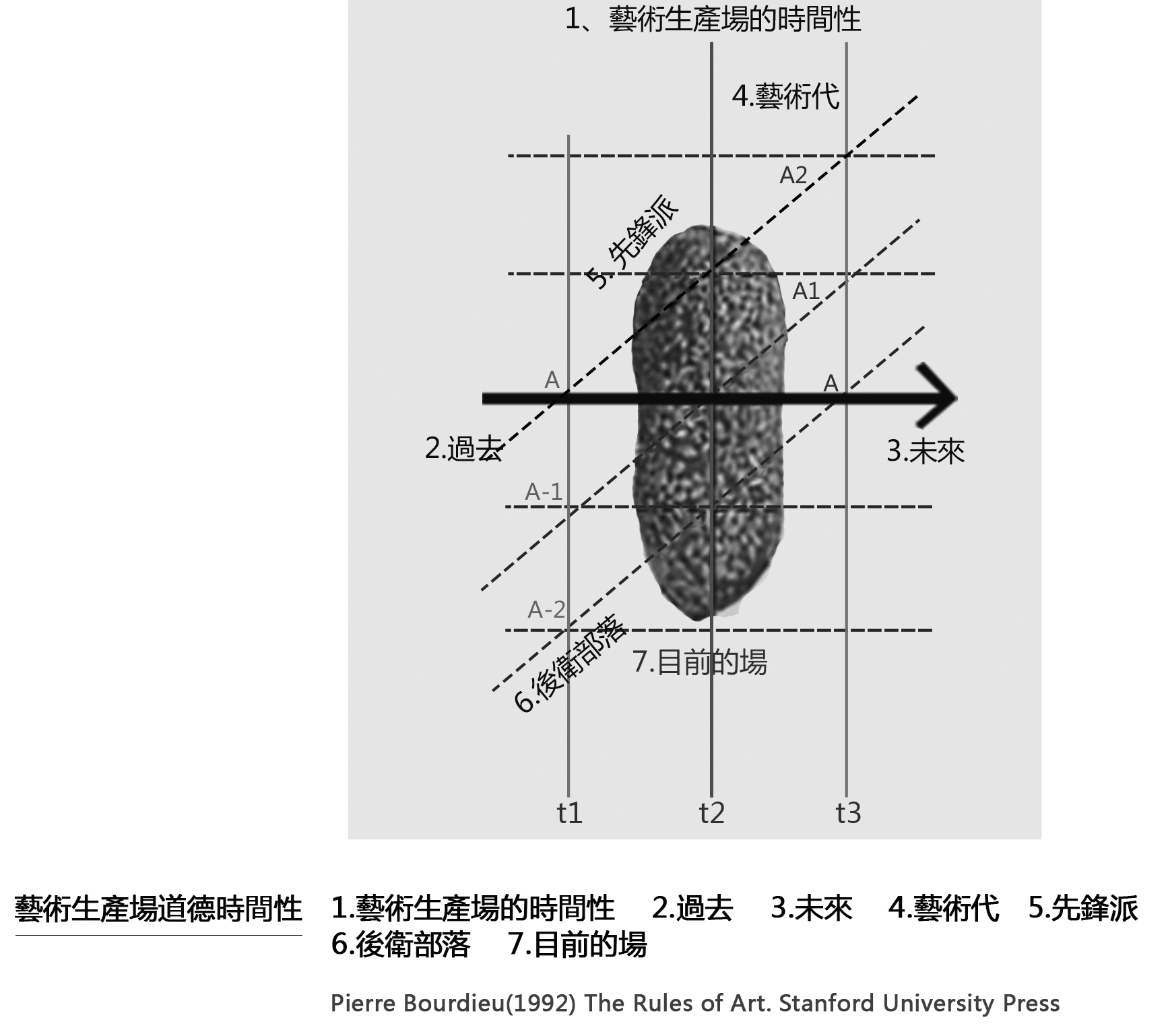

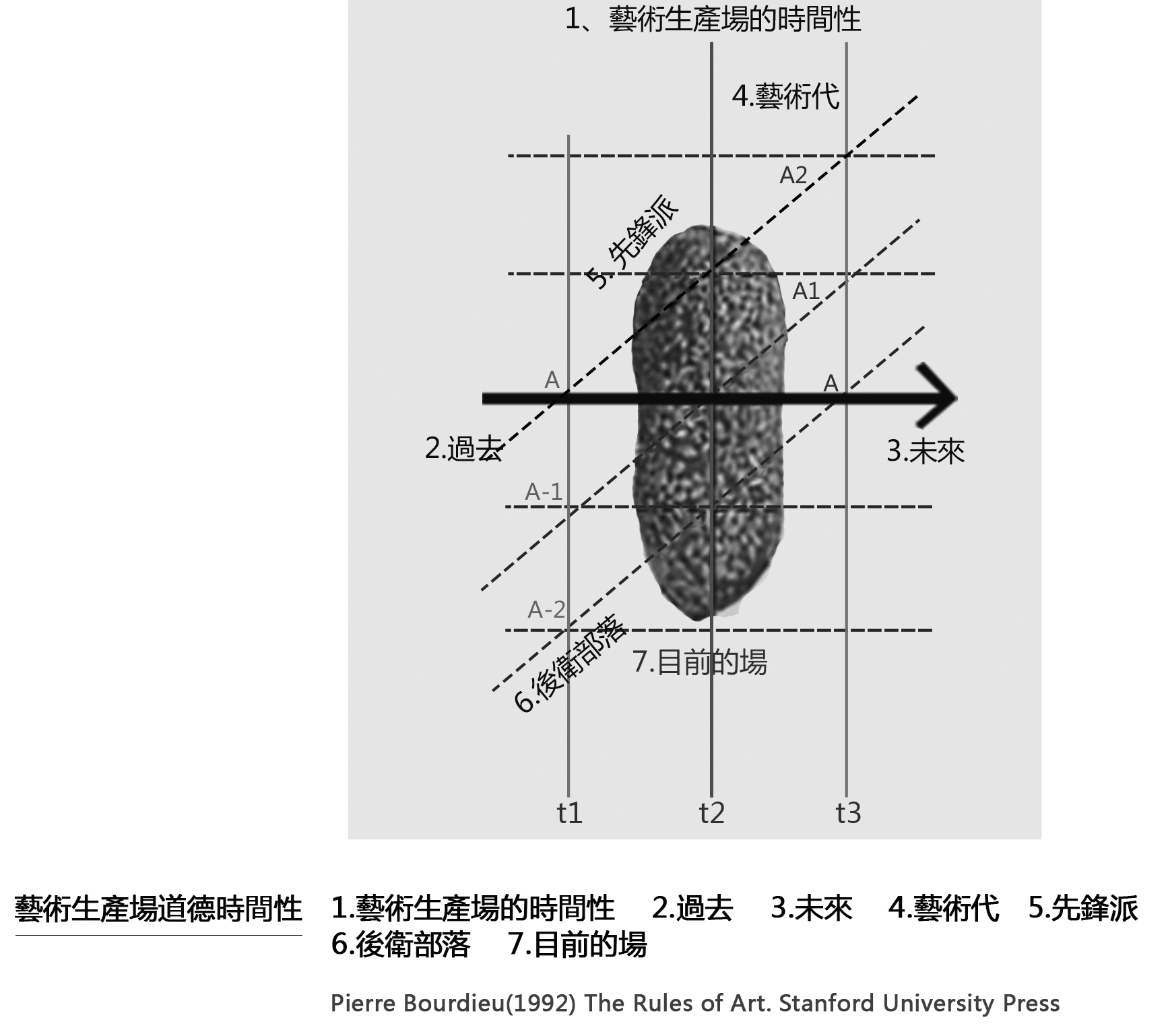

This diagram of the Muâ-Láu was drawn by Bourdieu when he was analyzing the state of the artistic field. I replaced the center shape of the original diagram with the traditional Taiwanese food, Muâ-Láu(taiwanese mochi). This is the way artistic generations exist in history. In the timeline from the past to the future, the avant-guard is always on the top line, that is, A to A2, the mainstream art is A-1 to A1, and the “rearguard” is A-2 to A. These three lines can also be read more simply, when an artist, such as A, belongs to the avant-guard in the past, and when going to the center along the time axis, becomes a mainstay of the mainstream, and if goes to the future without any change, he/she falls into the ranks of the rearguard. In fact, the field of artistic production that is recognized by the power and system is inside Muâ-Láu, that is, the artistic field, and “artistic generation” refers to the right half of Muâ-Láu, the block from the present to the future.

In a temporal social field, there is no fixed art generation. Any avant-garde art has a chance to become mainstream art, but if it is too avant-garde, it will be out of the range recognized by the artistic field. It is through this diagram that we can understand how the artistic subjectivity we are talking about is created within the social structure, and thus has a corresponding set of practical knowledge. The avant-garde in the past may have been marginal and progressive, but if it survives, it occupies a leading position in contemporary artistic production; if it does not renew itself, it will go out of the artistic field, and anything that is too radical or too conservative will be excluded from the artistic field, and the artistic field in the center is the result of artistic production, which is the dynamic process of the artistic field.

The production of social field also needs to be viewed historically. Manfredo Tafuri, a very important architectural historian of the Venetian School, once said in a short interview (There Is No Criticism, Only History)[4] that all architectural criticisms (including art criticisms) have one main problem: critics are doing the reproduction of ideology. If we divide art criticism into several types, the first type is called operational criticism, for example, when we see a piece of work, we will say that the work will be better if it is modified in this or that way, or how to change the way of arranging it so that the sense of space will be better, as if helping the artist to decide how he/she can be better, which is a kind of instrumentalist or patchwork type of operation; The second kind of criticism is called ideological reproduction, which is just talking about the artist's works and ideas in accordance with them, for example, when talking about Chen Chieh-jen's work “Happiness Building I”, how it may be a micro-perception and temporary community, the commentator is actually just copying the artist's ideology, and then helping him to produce it once again. For Tafuri these are not criticisms, for him only criticisms of ideology are criticisms. Criticism is a kind of demystifying work, and the real function of criticism can only be achieved by history. Criticism is a kind of demystifying work, and the real function of criticism can only be achieved by history. Historians must create a kind of artificial distance to carry out criticism, to have an insight into the differences of the times and the mentality of any given period, to have a continuous reflection on the artist's biography and the series of works, and to have a reflection on historic cycle. Only by doing so can criticism not be reduced to ideological reproduction. In order to appreciate the field of artistic production and to discern historically the logic of change in the field, and thus to engage demystifying work of criticism, we can begin with the history of the emergence of subjectivity in modern Western art.

2. Europe: Double Rejection Structure

Both Baudelaire and Flaubert were active around the 1840s, which was the time of the birth of artistic modernism in general, as Baudelaire once said:

It is painful to note that we find similar errors in two opposed schools: the bourgeois school and the socialist school. ‘Moralize! Moralize!’ cry both with missionary fervour.[5]

There were several important revolutions in France, the guillotine of Louis XVI and Empress Marie from 1789 to 1793, which affected the whole Europe; the July Revolution in 1830, which destroyed the Bourbon dynasty; the first republican system was established in 1848 by the middle class joining hands with the working class, and the rise to power of Napoleon's nephew Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, who was a republican at the beginning, and whose accession to the throne was the result of a union of the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, but he later made himself emperor in 1852, and led France from the Second Republic to the Second Empire (1852-1870). This revolution was a failure for Marx and led him to rethink the historical cycles and limits of bourgeois revolutions, as he did in his essay “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte” (1852). The period between 1842 and the founding of the Paris Commune in March 1871 (which overthrew Louis Napoleon) is the context in which the subjectivity of modern art emerged, the point at which we are now talking about the emergence of modernism. Baudelaire (1821-1867), Flaubert (1821-1880), Balzac (1799-1850), and a little later Manet (1832-1883), Monet (1840-1926), Cézanne (1839-1906), and other so-called (post)impressionists, all slowly became famous and influential in that era.

Artists at that time encountered a very fundamental problem: what could they do if they (bourgeois artists) no longer maintained a relationship of dependence with the royal family? In those days, the French royal family regularly organized salons, and artists could receive an annuity if they were rewarded by the French royal family for their participation in the salons. The new generation of artists often disdained this slavery contest, as in the case of veteran BBC art correspondent Will Gompertz's book What Are You Looking At?: 150 Years of Modern Art in the Blink of an Eye which depicts the interesting struggle between Impressionism and Classicism (the Royalists). There is a passage in the book that describes Monet, Manet and other artists sitting together in a coffee shop discussing the need to organize an exhibition, during which they mocked the Royal Salon as much as they could, what they wanted was to organize their own “real” art exhibition. [6] However, they also disliked those poor artists and art students (which was related to the addition of many new art universities in Paris at that time) from the Latin Quarter who lived on the Rive Gauche in Paris at that time, such as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, these anarchists. They believed that art should not serve the royal class, but neither should it serve the people or society. This was the dilemma that artists such as Baudelaire and Flaubert (who, let's not forget, were riches-to-rags bourgeoisie) desperately wanted to solve at the time.

Looking at the development of art throughout Europe since the Renaissance: the needs of the bourgeoisie produced the art market, and only later the requirements of the artists themselves. Artists went from being commissioned by royalty in the early days (artisans) to the emergence of galleries (professional artists), a transition that was gradually completed from the 16th century to the 1840s, when the artist in the free market appeared, and the discourse of the artist's subjectivity appeared.

The subjectivity of European modern art was accomplished through a double rejection, resisting social art, that art should not serve the people, and resisting art that serves the royal family. Art should and can only be “art for art's sake”, which is the autonomy of modern art that was slowly built up during the two popular revolutions in France. The artists constructed the field of artistic autonomy of the bourgeoisie itself through a structure of double rejection. At the same time, such class-specific social identity and aesthetic perspective were constructed together, which makes it possible to understand that the subject matter of the paintings of the French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists in the period from 1870s to 1910s was always related to the implication of “leisure” in the context of the class struggle, according to the renowned British art historian and art critic T. J. Clark. [7] During this period, the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists painted a great many subjects depicting middle-class urban landscapes and leisure life in a way that the royal painters could not have imagined. Previously unseen urban middle-class life, street scenes, picnics on the lawn, cafes, bistros, barmaids or ladies' costumes became the subject of paintings. Obviously, modern urban life was a new experience for the artist, and the time-space structure built class consciousness and class aesthetics, and paintings with similar themes were a way for this class to “enjoy” and identify with the new urban life that was emerging. And let's not forget that this was a Paris transformed by Georges-Eugène Haussmann, the beginning of a modern urban planning area that demolished the old city and its old life, replacing the alleyways of the old downtown area with wide boulevards, avoiding the resurgence of barricade battles and making it easier for the regime to repress popular revolutions with its armies. On the other hand, the aristocrats of the Île de la Cité on the Seine and the high society of Montmartre isolated forever the bohemian youth of the left bank of the Seine, the poor art students, the anarchists, which was the beginning of the bourgeoisie's spatial division of classes through the urban plan.[8] The fabulous urban life of leisure for Cézanne and Manet was based on a spatial plan that separated the rich from the poor and prevented revolutions. Art is not merely a reflection of one's own ideology; the process of making art involves how the artist in a given situation represents the world in relation to himself. In a specific spatial (French impressionist urban life and Haussmann's renovation of Paris) and historical conditions (France between 1848 and 1871), the bourgeoisie and the Petit Bourgeoisie, in order to differentiate themselves from the other classes, consciously (partly reflected the conditions of their own class, but not necessarily) created a class for themselves. This explains the relationship between artists' conscious aesthetic creation and social practice.

3. The United States: Artistic Subjectivity in the Culture of the Cold War

It was not until the 1940s and 60s that the subjectivity of modern art in the West was finalized by Clement Greenberg, who established the “resistant subject”. Grant Kester, in Conversation Pieces, continued Bourdieu's view: “The only refuge for the artist disenchanted with socialism and disgusted by capitalism was to withdraw into a resistant subjectivity and to reject ‘comprehensibility’ entirely. ”[9] Kester's critique is socio-historically conditioned by his rejection of the European subject of modern art, thereby establishing a set of anti-(European) elitist modes of artistic production, he says:

This receptive openness to the world runs throughout avant-garde discourse, in Bell’s and Fry’s rejection of normalizing representational conventions, in Greenberg's assault on the clichés of kitsch, and in Fried's criticism of theatrical art that shamelessly importunes the viewer. In each case, however, it is assumed that this openness can be purchased only at the expense of an indifference to (or assault on) the viewer and his or her associations and prior experiences. Once the work interacts with the viewer through a shared language, familiar visual conventions, or even an implicit acknowledgment of the viewer's physical presence in the same space, it sets off down the slippery slope of violence and negation.[10]

For Kester, European artistic autonomy precluded the possibility of dialogue, and any work with an intent and function that could be comprehended or interpreted was a popular and despicable object. However, the “dialogical framework” he proposes exempts the work of art, freeing the artist from aesthetic form and ethical imperatives, and transforming speaking for the people into letting the people speak for themselves, without guaranteeing the validity of the people's speech or making political judgments about letting “what kind” of people to speak. Artists are not responsible for the form of their work, because it is the result of people's participation or continuous dialog. In this way, the connotation of social art as a voice for the underprivileged (workers, students, the poor and the needy) is canceled out, and the people become nothing more than a mass of individuals.

Kester's “democratization of aesthetics” has its origins in the continuation of the cultural Cold War ideology. Since World War II, the U.S. has been promoting abstract expressionism to Europe through the CIA and the Rockefeller Center in an attempt to move the center of art from Paris to New York. “Culture is the propaganda of the Cold War,” and “Abstract Expressionism is the weapon of the Cold War,” are the opening statements of many contemporary art textbooks. Artists such as Jackson Pollock are often derided as Cold War warriors, as Louis Menand noted in his 2005 “Unpopular Front” article in The New Yorker. It has long been no secret that the Cold War was a cultural struggle. Even the Fulbright Program, which was established in 1946 to play the same role as the CIA, was a product of Cold War thinking. Eva Cockcroft's article makes it even clearer.[11] American cultural propaganda was aimed at the elite abroad, left-wing or left-connected, or sympathetic to the Soviets or Maoists, so that they would still maintain an avant-garde left-wing ideology, but only as long as they were anti-Communist, which was America's post-war global strategy.

The feeling that art has nothing to do with the CIA or Rockefeller Center happens to be an illusion that art maintains neutrality to stay clean. Foundations, universities, and cultural centers are important tools to actively compete with the European and Chinese left-wing and to seize its own artistic positions. In addition to the active promotion of their own political aesthetics, on the other hand, the semi-colonial “embassy art” was used as a cultural weapon in the Cold War.

Taiwan's naïve painter Hung Tung is the best example. Hung Tung's first solo exhibition was at the Lincoln Center of the U.S. Information Service in Taipei (1976), and in 1987, the The Artist magazine at the American Cultural Centre in Taipei held a retrospective after his death. It was only after the retrospective that the Tainan Cultural Center collected three of his paintings. In total, Hung Tung painted more than three hundred paintings in his life, and eventually died in poverty. His first solo exhibition was organized by the American Cultural Center, and his retrospective exhibition after his death was also organized by the American Cultural Center. Under the strong promotion of the United States, it seems that Taiwan only became aware of the existence of this figure, and then the Tainan Cultural Center collected him, which is nothing more ironic than the fact that something native to Taiwan was “invented” by the United States. Another example is the Iowa International Writing Program, which many early Taiwanese literary figures and artists attended, such as Chen Ying-chen, Lin Hwai-min, Chiang Hsun, Kao Hsin-kiang, Ya Xian, Tai Ching-nung, Xiang-yang, Shang Qin , Wei Tien-chung, Guan Guan, Yao Yi-wei, Yin Yun-peng, Ji Ji, Ge Chu, and so on. This shaped the ideology of early Taiwanese literature and art, bringing back to Taiwan the ideology promoted by the United States, and is the reason why the literary tradition of modernism in Taiwan is so close to American values. Lin Huaimin on modern dance is the best example. The same is true for the mainland, such as the art in Beijing's embassy district around the 1980s, like Ai Weiwei's “Black Book” and the subsequent 1989 Modern Art Exhibition, which started in the embassy district. The history of art in both Taiwan and mainland China has been influenced by the economic and cultural strategy of the United States, which was rolled out under the Cold War mentality.

If the European historical avant-garde was concerned with how to sew up the rupture between elite art and daily life, how to break through the boundary between high and low art, and how to actively challenge the monopoly of art production by art institutions, and Dada, Surrealism, and the Fluxus of the 1970s all had this characteristic, which demonstrated the reflection and resistance to the gradual specialization and institutionalization of modern art, then what the United States needed in the post-war period was not to challenge elite art and art institutions, which it did not yet have, which explains why Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art seemed so distinct from each other, yet the two trends did not clash in breaking new ground for American political forms of aesthetics. At the same time, the United States has continued to build large art museums and institutions, such as MoMA, to increase its influence on culture and the arts. We might say that the United States ended rather than inherited the European historical avant-garde, and that the United States replaced the European historical avant-garde and the intellectual critique of the system with the post-modern, Pop Art-toned, commercial mechanisms of giant art institutions and commercial galleries.[12]

Modern art subjectivity in the United States has some more complex processes that deserve deeper investigation. Those who escaped from post-Greenberg art practices in the 1960s and 1970s combined the original British tradition of community art with the new genre of public art in the United States, and through their works, curations, and discourse, they spread it outward as the United States gradually gained a position of global dominance. After the 1980s, when the cultural weapons of the Cold War gradually lost their effectiveness, artists and curators mainly from Britain and the United States searched for practices that could replace the Eurocentric art theories to break the impotence and rapid commercialization of 1960s American Pop Art in its later years, and to replace the unfulfilled mission of the European historical avant-garde with the main axes of artistic practical knowledge that were formed by democracy, dialogue, and participation. Examples include Kester's Conversation pieces, mentioned above, which emphasizes connective knowledge, dialogical frameworks, and practical art operations[13]; Suzanne Lacy's New Genre Public Art[14]; Ian Hunter and Celia Larner's littoral art; Claire Bishop's participatory art[15]; and French art critic Nicolas Bourriaud's discussion of the aesthetics of relationship[16]. We can reread Kester's words thus: “through the walls of (European) galleries, directly facing the (American) world, combining new forms of inter-subjective interaction (media) and social movements (of American democracy).”[17]

In short, Dadaism, Italian Futurism in the 1920s, Surrealism and the International Situationists in the 1960s endeavored to push art into a social and political framework. After the 1960s, when Soviet-style heroic realism fell out of fashion, when the Cultural Revolution was being carried out in mainland China, and when Europe was devastated by the war, this ideological gap was filled by the United States, and in the 1980s Danto and others, who pushed art to the end of history, affirmed postmodernity and its political aesthetics[18], abandoning all efforts at the unfinished project of modernity (Habermas's concern). [19]Arthur C. Danto's statement that “everything is a work of art” or Joseph Beuys' “everyone is an artist” did not change the way art was produced, only the way it was recognized. Naïve painters, even if they appear in large numbers, will never become professors of art in the academy. As Danto himself admits, “It's just that artists blow their own trumpets and act individually.” These statements are essentially nothing more than the thickening of a catalog of aesthetic values through market certification, academic deployment, and the production of aesthetic styles. The late Anglo-American model of countering Eurocentrism is a history of a struggle for space from political struggle (the structure of the Cold War) to the “democratic discourse” of aesthetics (the Cultural Cold War). While Europe initially built a wall (artistic subjectivity) and then tried to break it down (between the elite and the public), the United States has always tried to sell itself beyond the wall.

The globalization of the aesthetics of democracy has an affinity with the global promotion of American democracy. The most representative of the aestheticization of American democracy is Andy Warhol, who once said that McDonald's is the most democratic place in the world, and that whether the president goes to get a McChicken nugget or the average person goes to get one, the contents are the same, and they don't give you a little bit more just because you're the president. What he doesn't say, however, is that the people of the world have become more obese and less nutritious because of the rise of McDonald's, throwing away traditional foods and the cultures associated with them, and that fast food doesn't eliminate classes but borders. There is nothing more wonderful for capitalists than the fact that whether it is a president or a civilian, China or Africa has to pay the bill. The subjectivity of modern American art has to do with the fact that the United States achieved a meaningful role in global world history after the structure of the Cold War (Hegel's point of view), and it is only then that we can understand why the idea of participatory art, such as creative conversation art, new genre of public art, and so on, can so quickly turn into another paradigm of practice. [......]

3. Towards Societal Art

1. Porous Combat

The above systems of knowledge for organizing sensible materials: workification, affective bond of particular tribe, re-historical-spatialization, are ways of artistic reproduction, which constitute a productive relationship with artistic production, treating the situation that can be practiced in the future as a possibility to intervene in the discussion of the present reality. However, at the level of artistic production, it is still necessary to reforge the knowledge of artistic production, what I call “Societal Art,” or what can be called an insurgent theory of artistic practice.

The first strategy towards societal art is to imagine a “porous combat”. Let me illustrate the significance of this by borrowing from David Harvey's chapter “The insurgent architect at work” in Spaces of Hope. [20] Harvey believes that the political practice of insurgent in each particular space and time is a long frontier, and that everyone has free will and creativity, and is not a solid of labor under capitalism, and that everyone has the porousness that makes it possible for them to become a political person. In the face of the “theater” of different thoughts and actions, it is important that we see each other. Harvey proposes eight long frontiers of theater: the personal is political, social construct, politics of collectivities, militant particularism, mediating institutions and built environments, translations and aspirations, moment of universality, and socio-ecological orders. He reminds us that the architect is a figure of resources and world-building, and that we are all “translating” the aspirations of people in different historical and political contexts, which they intend to translate into the real world. It is important that we become committed to being an insurgent architect, “armed with a variety of resources and desires, [……] can aspire to be a subversive agent, a fifth columnist inside of the system, with one foot firmly planted in some alternative camp.”[21] No one is on the outside of capitalism, and the base of the porous combat is the imagination and practice of insurgent from within, and how could it be otherwise by replacing the architect above with an artist?

Neoliberalism is like cheese, with many holes and crevices within the solid. Some people see resistance in the cracks as the whole of resistance, while others see resistance within the cracks as despicable, useless resistance. How are we to connect the aspirants in these holes and crevices into favorable channels of destruction? If we only think about presenting ourselves in the same cultural field, seeing the combats in our own theater, obsessed with the success of our own theater without having a global view, without seeing what other comrades in the trenches on the frontier are doing, it is impossible to create a truly meaningful connection of resistance, and the artist is ultimately happy to achieve a victory in the marketplace, and is enthusiastic about his residency in the village to help builders to beautify the neighborhood and increase floor area ratio, Even in the frenzy of contemporary global biennials, issue-oriented and political art is only a way to gain access to the spotlight of this single theater, without any meaning of resistance outside of this field. The basis of the possibility of a porous combat lies in how firmly one foot is planted in the camp of alternatives. Turning the present into presents, or a present, does not see the current facts as the only, inevitable present. Our present and future are connected to understanding various realities, so we need to start collecting archives. Collecting changes in global and local development, that is, making a reality into a possible future, is Foucault's archaeology of knowledge: we have to collect different kinds of archives, alternative chorology-historiography. More importantly, in the face of the increasing global division of labor and professional differentiation, art practice should return to the path of reflection of Lefebvre's critique of everyday life and Michel de Certeau's practice of everyday life, and begin our tactics.[22]

2. The Practice of “Pleasure” without Ownership

All art is concerned with pleasure. Marx said that pleasure was the monopoly of the bourgeoisie, that most pleasures were reserved for a particular class of people who were socially privileged enough to enjoy them, and who had made their standards universal, just as aesthetic feeling were. However, art is ultimately a form of sensibility, and the new task is to start from the pleasure of the alien, the underclass, the divergent, and to find in the “shaman” and the “inaudible” a way of politic pleasure that can be opposed to police pleasure, and to find a new pleasure that has the ability to invert the relationship. It belongs to the reader, to the spectator, outside the art museum, as Roland Barthes reminds us in literary theory, but remains to be developed in art. The politics of pleasure is the re-empowerment of the subject through pleasure. Art, as John Dewey said, is an experience, and the recovery of lost experience is the core issue of the politics of pleasure.

What kinds of things give us pleasure? What kind of things give us no pleasure? The source of every pleasure has to do with exclusivity. Edward Said, in his book Culture and Imperialism, quoted a 14th century Indian scholar who said, “The man who finds his homeland sweet is still a tender beginner; he to whom every soil is as his native one is already strong; but he is perfect to whom the entire world is as a foreign land. The tender soul has fixed his love on one spot in the world; the strong man has extended his love to all places; the perfect man has extinguished his.”[23]This echoes Said's emphasis that the true intellectual is always the homeless. I would like to interpret this in a different direction: This echoes Said's emphasis that the true intellectual is always the homeless (homeless). I would like to interpret this in a different direction: the roots of our love of the land, our identity with the countryside, or our love of Taiwan are all related to the exclusivity of the land. It means that the love of place is a sense that develops out of not questioning ownership, that I love my home because it is “mine”, and how can I love my home if I don't have the land? How can we imagine loving a place that doesn't belong to me, that doesn't have a home for me, and developing a rich, long-term love of place? Cities of migration and arrival cities are places where people seek to live, not a fixed love of land. The possession of land, the history of possession, grows into a love of native soil, a love of country, but this happens to be the love of place ensured by the ownership of property. Think of those who do not own land? For example, some second-generation foreigners, urban and rural immigrants, urban aborigines, I long to love ...... but where is my hometown? The reason why some of Taiwan's unauthorized communities and older neighborhoods facing urban renewal are worth fighting for is not all because people have a history of having lived here, or just against the loss of habitable places for residents, but against public land becoming land for private consortia to build on. Sometimes this feeling of love for the land that we have extends to invading the rights of others. The feeling of pleasure, love, and the intention of love and lust are all related to exclusivity. When it comes to talking about porous combat, we must leave belonging. When loving a community, loving Taiwan, loving the world, is it loving Taiwan from the world's point of view, from Taiwan's point of view, or from Taipei's point of view? Different political practices have different answers, but the answer of belonging happens to be the least necessary one. As an artist, imagining one's own feelings to narrate to the world will have a very different result from imagining what kind of art an ordinary family needs, and in the international art arena, imagining how to speak for Taiwan is very different from imagining how to speak to the world about the sympathetic structure of the Third World.

In addition, the Seattle anti-World Trade Organization movement in 1999 blossomed into a rich and varied “art style” that brought together pleasure, joy, revolution, and artistic action, as Naomi Klein, author of No Logo, puts it, “all forms of resistance movements, a million arrows in the air.”[24] And as documented and described in her book The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism: a new scenario in which art is both content of action and form; how it is produced and how it might be practiced on the streets.[25] The slogan of cultural action in the 1990s, “Art for all or not at all,” replaced the “Let the imagination take over” of the 1960s student movement. This “porous frontier” of parallel rather than tandem connections offers the possibility of collaboration between wandering subjects, which we may have glimpsed at the 2008 Taipei Biennale, but where the real art did not take place. “Art for all or not at all” is certainly not a truth, but it is interesting that it is so old and simple that we have almost forgotten it, so now we can once again ask, if we think of art in this way, what might it become?

Thinking back to the precious legacy left by Dadaism and International Situationism, International Situationism and Dadaism transformed the “given reality” into a collapsing joke that challenged aesthetics, institutional production, political rhetoric, and totalitarianism, and forging the poetics of everyday life into a weapon that could challenge bureaucratic production. By beginning to imagine the need for art in everyday life, the artist may have changed the way art is made, by imagining the possible needs of the general public for art, by imagining that art comes from the home rather than from galleries and museums. This could revolutionize many different possibilities and strategies of artistic practice.

3. Politics of Recognizing Difference

The second characteristic of societal art is the shift from the politics of resistance identity to project identity. Resistance identity is a closed affective bond based on affect, lineage, and community. Resistance is generated by external insults, such as a community's opposition to the presence of a power substation in the neighborhood, or to the installation of a neighboring AIDS hospital or garbage disposal site. Because resistance is inherently fraught with elements of refusal, it is also difficult to avoid the pitfalls of narrow communitarianism, i.e., “Not in my back yard”. This is a reminder from many urban researchers, including David Harvey: “although community ‘in itself’ has meaning as part of a broader politics, community ‘for itself’ almost invariably degenerates into regressive exclusions and fragmentations (what some would call negative heterotopias of spatial form).”[26] We need to learn to start from a resistant identity and then turn around and slowly transition to a reflexive project identity. In other words, we support the anti-relocation movement of the New Taipei City Losheng Sanatorium not because we are residents of Losheng, nor do we have any personal interest in it, but because we know that the choice of the MRT route and the plan are absurd and unjust from beginning to end, and we agree that the resistance practiced by the residents is just, rather than a matter of our own rights. Project identity involves a new kind of politics, one that recognizes the texture and functioning of identity, the goals and oppositions of identity, and is transformed into self-identity through reflexive project.[27] This is the ability to mapping, the politics of recognizing difference.

Taiwan's mainstream community discourse, or the art engaging the community, art engaging the locality that depends on it, which was meaningful in the 1990s, now seems conservative and stagnant, and the current issue is no longer to create community identity but to ensure the existence of its differences. Identity politics involves the pitfalls of political correctness and a narrow sense of community, often leading artists into simple positional judgments and complicity with the dominant sense of community. In postmodern claims and considerations of social justice, art needs to safeguard the reproduction of differentiated cultural relations, rather than guaranteeing the established welfare of communities and asserting power for them. For example, how can social justice and urban art be discussed? Where is the just art for just city? Art beautifies the city, increases floor area ratio, generates huge wealth for city developers, gives the middle-class access to high-class art institutions, and increases the price of land in the city, but who really benefits? Who has lost the right to live in the city? A citizen who spends an hour commuting to the Taipei Fine Arts Museum to see an exhibition or visit the Taipei Expo Park may not realize that it is these expensive exhibitions that make him live farther and farther away, or, is it any wonder that the farther away from the location of the exhibition he lives, the higher the value of the aesthetics that the artwork touches him? We need more actors who would rather work with marginalized communities than with middle-class communities and institutions.

4. Reality Engagement

Alain Touraine, who studies the labor movement and post-industrial sociology, once talked about a kind of sociology in his book The Return of the Actors, which is moving. If there is a kind of sociology called actionalist sociology, then this kind of sociology teaches us that sociology is actually produced by researchers together with the people, in order to solve the people's problems, and that the production of social theories is a way of letting the people solve their problems through theories rather than anesthetizing them to make them forget or explaining their problems from the heaven, which he felt was true sociology.[28] What about art? Is there an actionalist art that is produced for the artist together with the perceptual material (or object) he or she wants to work with, and the viewer, to learn from each other and to solve problems at the same time?

The popularity of art engaging community/space seems to be a spatial extension of Kester's “conversation pieces,” but art has never seriously considered the role of the community in history and the current operation of power. The community was first a local organization that received subsidies during the US aid period, but later became a subject in the community development, and became the basis for the jigsaw puzzle of the subject in the new Taiwanese culture.

The process of community development in Taiwan can be roughly divided into three stages. The first stage is the community master building that was vigorously promoted by Chen Chi-Nan when he was the chairman of the Council of Cultural Affairs in 1993. Before that time, the community had never been given any democratic rights, and no one would be informed in advance of what the people's homes were going to become, and it was only when the announcement was made three months before that the people would know that the front of their homes were going to be turned into a road or a park, and the policy of the community development was to let the people who had never been given the right to democracy to begin to enjoy the right to speak; The second stage is to make the expression of democracy into a viable political operation, the community began to operate in the architectural field, and the community planner system allowed the advantaged community to exclude the unwanted and to fight for more resources; In the third stage, after 2000, for artists or community workers to engage the community, it is no longer a matter of listening to their expression of democratic will, or not only supporting their opportunities for political practice, but also a matter of struggling with the power within the community, struggling with the community with different power relations, or else doing nothing is the presentation of the dominant opinion of the community.

This is the true meaning of engage in reality. Engagement does not mean abandoning the subject and the political position; on the contrary, that is socialization. Engagement is the act of expressing one's political practice in front of a public, where public space emerges. Engagement is production, it is political practice, and it is political practice, as Nannah Arendt repeatedly reminds us, that guarantees public space, not the other way around. Historically, the tendency of art to engage with communities, spaces, and folklore, emphasizing participatory processes, has not solved the ethical imperative of art, but rather dissolved it or “suspended” it. Dissolution differs from revolution: the former removes the barriers of judgment, effectively allowing reality (power) to become the unquestioned arbitrator, while the latter reverses the hierarchies imposed by political and social classifications, which vary across different historical stages. Participation is not an end in itself of art, just as political correctness is not about increasing identity but increasing difference. Nor is participation participation for its own sake, but rather the recognition of the difference between oneself and the multitude. Strictly speaking, “socially engaged art” is not valid; there is no art that is outside of society. Engagement with social reality is not about making art, or seeing art as the centerpiece of social engagement, but about answering the question of how to reverse the power operations of social engagement. Engagement and political correctness are not promises of good art, but rather Benjamin's “places himself on the side of the proletariat” is, because the struggle for art is not between capitalism and aesthetics, but between capitalism and the proletariat.

How can contemporary art practices collaborate with their objects of study (objects of representation) to develop a method and create artworks? I wouldn't claim that this is the only way to produce art, but it should at least be recognized. To engage with reality, on the one hand we must master the socio-political process, and on the other hand it is precisely my attempt in recent years to dedicate myself to field research, to learn to communicate with the different masses. The field is the theater. Artists are very accustomed to speaking their own words, but once you engage with reality, when you feel a certain subject, when you feel a particular mass, at least you have to discuss with the object you want to represent how artistic practice is possible and what kind of knowledge you should have.

5. Summary

In the face of contemporary issues of pleasure, identity, and engagement with reality, it is all the more important for art practice to actively understand the knowledge of contemporary political and economic processes. [......]

Societal art is not political art. It does not deal with political aesthetics through manifesto or eventization, nor does it expose political conspiracies, nor is it judged as good or bad by whether it is politically correct or not; Societal art is not participatory art, it is not dialogue for the sake of dialogue, it does not aim at the ethical imperative of relieving art of its unique form, it does not constantly emphasize democratic expression (sometimes the opposite), it does not turn spaces, communities, groups into objects of representation, or into tools for the honing of creativity; Nor is societal art the social art of 19th-century Paris, the bourgeois sense of self-redemption that spoke for the underprivileged or dogmatically claimed for socialism, it is not for the middle class to see the display of the poor or of foreign cultures, but for the “other” to have the right to produce/access/use art, to claim the right to art. Societal art is based on historical diagnosis, on the understanding of the knowledge of political and social processes, on the re-acquisition of everyday life, on the redistribution of ownership, on field knowledge. Societal art is the action of articulating, it is the retrieval of the subject and the experience, it is the ability to map the theaters, it does not have a fixed methodology, it has a lot of different possibilities for imagining, producing, practicing a reproduction of differential relations. Societal art is counter- rather than anti-. It is social resistance rather than political confrontation, advocating for public histories as public art. It seeks to restore the histories, memories, customs, and rights of minorities, rewriting the history of the prey rather than retelling the hunter's triumphs, and it is thus a practical way to answer the question of what John Burger called “help people to proclaim their social rights”.

The word art is originally derived from the Latin ars, which has four meanings: the first is the common understanding of the word art as skill and technique; the second is the person who possesses such expertise, such as an artist; the third is the work done through such expertise; ars originally had another meaning that has been sidelined in the development of modern art. This lost meaning is most often recovered by activists: art is about people joining hands to accomplish something. For activists, art is not about turning the results of cultural action or social movement efforts into works or exhibitions; on the contrary, “the slogans, action theater that appear at the site of action, and imaginative forms of protest or the magical ways of organizing people to express their will are art.”

[1] 約翰.伯格, 觀看的視界, 吳莉君譯 (麥田, 2010).

[2] Pierre Bourdieu, The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field, trans. by Susan Emanuel, Meridian (Stanford Univ. Press, 1996), p. XV.

[3] Arnold Hauser, The Sociology of Art (University of Chicago Press, 1982), p. 92.

[4] Manfredo Tafuri, “There Is No Criticism, Only History”, in Book Review, No. 9(spring), 1986, pp. 8-11.

[5] Bourdieu, p. 47.

[6] Will Gompertz, What Are You Looking At?: 150 Years of Modern Art in the Blink of an Eye (Viking, 2012).

[7] Timothy J. Clark, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers (Princeton University Press, 1986), p. 204.

[8] David Harvey, Paris, Capital of Modernity (Routledge, 2004).

[9] 格蘭.凱斯特, 對話性創作, 吳瑪俐、謝明學、梁錦鋆譯 (遠流, 2006), p. 66.

[10] 格蘭.凱斯特, p. 80.

[11] Eva Cockcroft, “Abstract Expressionism, Weapon of the Cold War”, Pollock and After: The Critical Debate, ed. by Francis Frascina (Harper & Row, 1985).

[12] 安德里亞斯‧胡伊森, 大分裂之後, 王曉玨、宋偉杰譯 (麥田, 2010).

[13] 格蘭.凱斯特.

[14] 蘇珊·雷西, 量绘形貌-新类型公共艺术, 吳瑪莉譯 (遠流, 2004).

[15] Claire Bishop, Participation (Whitechapel, 2006); Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (Verso Books, 2012).

[16] Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics (Les Presses du réel, 2002).

[17] 格蘭.凱斯特, p. 23.

[18] Arthur Coleman Danto, After the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History (Princeton University Press, 1997).

[19] Jürgen Habermas, ‘Modernity: An Unfinished Project’, in Habermas and the Unfinished Project of Modernity: Critical Essays on The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity, ed. by M. P. d’Entrèves and Benhabib (MIT Press, 1997).

[20] 大卫·哈维, 希望的空间,胡大平译 (南京大学出版社, 2006).

[21] 大卫·哈维, p. 233.

[22] Henri Lefebvre, Critique of Everyday Life: The One-Volume Edition (Verso, 2014).

[23] Edward W. Said, Culture and Imperialism (Vintage Books, 1993).

[24] Naomi Klein, No Logo: No Space, No Choice, No Jobs (Flamingo, 2001).

[25] Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (Alfred A. Knopf Canada, 2007).

[26] 大卫·哈维, p. 235.

[27] Manuel Castells, The Power of Identity: The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture (Wiley, 1997), pp. 10–11.

[28] Alain Touraine, Return of the Actor: Social Theory in Postindustrial Society (University of Minnesota Press, 1988).

Translation by Lu Ruiyang

This article was originally written as a speech titled “History as ‘Diagnosis’” on February 5, 2013, when I accepted the invitation of Chen Chieh-jen and TheCube Project Space to give a talk at the “Forum on the Eve of Demolition” at the Happiness Building in Shulin District. I would like to thank my friends Chen Chieh-jen, Wang Mo Lin, Manray Hsu, Hou Shur-tzy, Hsieh Ying-chun, and Wang Jiahao for their valuable comments during the discussion. This paper has been edited by the author into a thesis format.

The only reason why art critic John Berger, even though he lives in seclusion in a rural village under the Alps and happily rides a heavy motorcycle, still wields his pen to write books is that he remains hopeful that visual world (art) can still serve as a critique of the real world, as he says: “I will judge the value of a piece of work according to whether it can help people to proclaim their social rights in the modern world. I hold to that.”[1] As a critic, Berger does not need to explain the relationship between artistic production and social rights, because art critics produce art externally, connecting the work to society through their own perspectives. Yet he leaves us with unanswered questions: what is the knowledge of artistic practice? What are social rights? Whose social rights? Can reflecting on social rights be a criterion for the knowledge of artistic practice? How does this differ from “literature as a vehicle for carrying the Dao”(文以载道) and the aestheticization of politics?

John Berg also reminds us that we cannot be moved by aesthetic emotion alone and beg the question about the relationship between art and nature, and between art and the world.

Art does not imitate nature, it imitates a creation, sometimes to propose an alternative world, sometimes simply to amplify, to confirm, to make social the brief hope offered by nature. Through the delicate white bird made of pine wood, which is often hung in almost every farmhouse in Eastern Europe, he asks us, “The white wooden bird is wafted by the warm air rising from the stove in the kitchen where the neighbours are drinking. Outside, in minus 25°C, the real birds are freezing to death!” It seems to suggest that this is the heart of the artistic practice: the two roles of visual world (art) in “replacing” or “confirming” the world.

In order to answer these two roles of art, and its relation to social rights, it is necessary to answer, first of all, where does our knowledge of artistic practice come from? How is it constructed and transmitted? Contemporary art theory has been subjugated to the philosophers' powerful pen, and aesthetic is carried out solely through their eyes, while the knowledge of artistic practice seems to be reduced to technology, those technical tools that we teach undergraduates, or marketing and management know-how. Worse still, artistic or aesthetic theories are not inspired by the artists' philosophies, but rather by the curators' mediation of various contemporary philosophical and social trends, or by the global biennial's need for “social turn” and “novelty”, and the knowledge of artistic practice is produced by teachers who speculate the market direction and maintain the mechanism of the academy. The knowledge of art theory and art practice involves different epistemologies (rather than the difference between epistemology and methodology). It is the difference between “What is art?” and “What should art be?” This paper examines the history of the production of subjectivity in Western art, and then [......] maps how the foundation of “What should art be” is shaped by the knowledge of historical social processes, so that there may be an opportunity to respond to the question of “What art can be”.

This paper attempts to prove a hypothesis with practical implications: “the knowledge of artistic practice is inseparable from the knowledge of socio-political processes”, and proposes an initial proposal of “Societal art”. Since I started teaching at the Art Academy, I have been thinking about what is the knowledge of artistic practice? Is it the principles, skills and tools of plastic arts? Is it aesthetics, philosophy, cultural theory or fieldwork, social research, participation? Is it cultural activism? Or is it really just life experiences? “Interdisciplinarity” is all the rage right now, but what knowledge of ‘inter-disciplinary’ artistic practice actually means is vague. In any case, aesthetics or artistic production is always subordinate to some kind of identity system, some kind of visibility, possibilities, and opportunities for dissemination and sharing. In Taiwan, the excellent students of top-notch academies have access to more alternative, leftist art theories, and have been nurturing the perennial winners of the big gallery and exhibition prizes. So, what does it mean to be politically radical and successful in the aesthetic marketplace? To understand this meaning, we must do two things with the discourse of artistic practice: re-historicize it and spatialize it. The purpose of historicizing and spatializing artistic production is to point out that no matter how reluctant we are to admit it, art, as a content with a particular form, is always closer to the objects of our disdain than we think. In Taiwan, art theory rarely confronts the dramatically changing spatio-temporal conditions of art's existence.

I. Art and Society: The Construction of Subjectivity in Western Modern Art

In his book The Rules of Art, Pierre Bourdieu cites Le Don des morts, written in 1991 by the famous French novelist Danièle Sallenave:

‘Shall we allow the social sciences to reduce literary experience – the most exalted that man may have, along with love – to surveys about our leisure activities, when it concerns the very meaning of our life?’[2]

Social scientists seem to be murderers of the aesthetic emotion, which is why the art world has always rejected social scientists as analysts, feeling that the aesthetic emotion and the inspiration to create are lost, that the work and the movement are “interpreted out”, and that the necessity to relate creative intentions to the social context deprives them of their autonomy. Arnold Hauser, an important left-wing sociologist of art, published his The Sociology of Art in German in 1974, which was translated into English in 1982. He once wrote:

“What remains beyond all doubt is that we can imagine a society without art but not art without society. ”[3] For him, art has to be seen in the context of social structure and history. While art is certainly a product of society, and artistic creation is subject to the class ideology of the established rulers, art also has the potential to respond to, criticize, and challenge the practices of established social institutions. The work of art is a dialectical structure, not just a form of content, not just a receiving “you” and a transmitting “I”, but a dialog developed through continuous interaction between the author and the viewer, a relational system of reciprocal references. Thus, society as a product of art is possible. I would like to begin my discussion with these two different perspectives.

1. Artistic Subjectivity

This diagram of the Muâ-Láu was drawn by Bourdieu when he was analyzing the state of the artistic field. I replaced the center shape of the original diagram with the traditional Taiwanese food, Muâ-Láu(taiwanese mochi). This is the way artistic generations exist in history. In the timeline from the past to the future, the avant-guard is always on the top line, that is, A to A2, the mainstream art is A-1 to A1, and the “rearguard” is A-2 to A. These three lines can also be read more simply, when an artist, such as A, belongs to the avant-guard in the past, and when going to the center along the time axis, becomes a mainstay of the mainstream, and if goes to the future without any change, he/she falls into the ranks of the rearguard. In fact, the field of artistic production that is recognized by the power and system is inside Muâ-Láu, that is, the artistic field, and “artistic generation” refers to the right half of Muâ-Láu, the block from the present to the future.

In a temporal social field, there is no fixed art generation. Any avant-garde art has a chance to become mainstream art, but if it is too avant-garde, it will be out of the range recognized by the artistic field. It is through this diagram that we can understand how the artistic subjectivity we are talking about is created within the social structure, and thus has a corresponding set of practical knowledge. The avant-garde in the past may have been marginal and progressive, but if it survives, it occupies a leading position in contemporary artistic production; if it does not renew itself, it will go out of the artistic field, and anything that is too radical or too conservative will be excluded from the artistic field, and the artistic field in the center is the result of artistic production, which is the dynamic process of the artistic field.

The production of social field also needs to be viewed historically. Manfredo Tafuri, a very important architectural historian of the Venetian School, once said in a short interview (There Is No Criticism, Only History)[4] that all architectural criticisms (including art criticisms) have one main problem: critics are doing the reproduction of ideology. If we divide art criticism into several types, the first type is called operational criticism, for example, when we see a piece of work, we will say that the work will be better if it is modified in this or that way, or how to change the way of arranging it so that the sense of space will be better, as if helping the artist to decide how he/she can be better, which is a kind of instrumentalist or patchwork type of operation; The second kind of criticism is called ideological reproduction, which is just talking about the artist's works and ideas in accordance with them, for example, when talking about Chen Chieh-jen's work “Happiness Building I”, how it may be a micro-perception and temporary community, the commentator is actually just copying the artist's ideology, and then helping him to produce it once again. For Tafuri these are not criticisms, for him only criticisms of ideology are criticisms. Criticism is a kind of demystifying work, and the real function of criticism can only be achieved by history. Criticism is a kind of demystifying work, and the real function of criticism can only be achieved by history. Historians must create a kind of artificial distance to carry out criticism, to have an insight into the differences of the times and the mentality of any given period, to have a continuous reflection on the artist's biography and the series of works, and to have a reflection on historic cycle. Only by doing so can criticism not be reduced to ideological reproduction. In order to appreciate the field of artistic production and to discern historically the logic of change in the field, and thus to engage demystifying work of criticism, we can begin with the history of the emergence of subjectivity in modern Western art.

2. Europe: Double Rejection Structure

Both Baudelaire and Flaubert were active around the 1840s, which was the time of the birth of artistic modernism in general, as Baudelaire once said:

It is painful to note that we find similar errors in two opposed schools: the bourgeois school and the socialist school. ‘Moralize! Moralize!’ cry both with missionary fervour.[5]

There were several important revolutions in France, the guillotine of Louis XVI and Empress Marie from 1789 to 1793, which affected the whole Europe; the July Revolution in 1830, which destroyed the Bourbon dynasty; the first republican system was established in 1848 by the middle class joining hands with the working class, and the rise to power of Napoleon's nephew Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, who was a republican at the beginning, and whose accession to the throne was the result of a union of the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, but he later made himself emperor in 1852, and led France from the Second Republic to the Second Empire (1852-1870). This revolution was a failure for Marx and led him to rethink the historical cycles and limits of bourgeois revolutions, as he did in his essay “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte” (1852). The period between 1842 and the founding of the Paris Commune in March 1871 (which overthrew Louis Napoleon) is the context in which the subjectivity of modern art emerged, the point at which we are now talking about the emergence of modernism. Baudelaire (1821-1867), Flaubert (1821-1880), Balzac (1799-1850), and a little later Manet (1832-1883), Monet (1840-1926), Cézanne (1839-1906), and other so-called (post)impressionists, all slowly became famous and influential in that era.

Artists at that time encountered a very fundamental problem: what could they do if they (bourgeois artists) no longer maintained a relationship of dependence with the royal family? In those days, the French royal family regularly organized salons, and artists could receive an annuity if they were rewarded by the French royal family for their participation in the salons. The new generation of artists often disdained this slavery contest, as in the case of veteran BBC art correspondent Will Gompertz's book What Are You Looking At?: 150 Years of Modern Art in the Blink of an Eye which depicts the interesting struggle between Impressionism and Classicism (the Royalists). There is a passage in the book that describes Monet, Manet and other artists sitting together in a coffee shop discussing the need to organize an exhibition, during which they mocked the Royal Salon as much as they could, what they wanted was to organize their own “real” art exhibition. [6] However, they also disliked those poor artists and art students (which was related to the addition of many new art universities in Paris at that time) from the Latin Quarter who lived on the Rive Gauche in Paris at that time, such as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, these anarchists. They believed that art should not serve the royal class, but neither should it serve the people or society. This was the dilemma that artists such as Baudelaire and Flaubert (who, let's not forget, were riches-to-rags bourgeoisie) desperately wanted to solve at the time.

Looking at the development of art throughout Europe since the Renaissance: the needs of the bourgeoisie produced the art market, and only later the requirements of the artists themselves. Artists went from being commissioned by royalty in the early days (artisans) to the emergence of galleries (professional artists), a transition that was gradually completed from the 16th century to the 1840s, when the artist in the free market appeared, and the discourse of the artist's subjectivity appeared.

The subjectivity of European modern art was accomplished through a double rejection, resisting social art, that art should not serve the people, and resisting art that serves the royal family. Art should and can only be “art for art's sake”, which is the autonomy of modern art that was slowly built up during the two popular revolutions in France. The artists constructed the field of artistic autonomy of the bourgeoisie itself through a structure of double rejection. At the same time, such class-specific social identity and aesthetic perspective were constructed together, which makes it possible to understand that the subject matter of the paintings of the French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists in the period from 1870s to 1910s was always related to the implication of “leisure” in the context of the class struggle, according to the renowned British art historian and art critic T. J. Clark. [7] During this period, the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists painted a great many subjects depicting middle-class urban landscapes and leisure life in a way that the royal painters could not have imagined. Previously unseen urban middle-class life, street scenes, picnics on the lawn, cafes, bistros, barmaids or ladies' costumes became the subject of paintings. Obviously, modern urban life was a new experience for the artist, and the time-space structure built class consciousness and class aesthetics, and paintings with similar themes were a way for this class to “enjoy” and identify with the new urban life that was emerging. And let's not forget that this was a Paris transformed by Georges-Eugène Haussmann, the beginning of a modern urban planning area that demolished the old city and its old life, replacing the alleyways of the old downtown area with wide boulevards, avoiding the resurgence of barricade battles and making it easier for the regime to repress popular revolutions with its armies. On the other hand, the aristocrats of the Île de la Cité on the Seine and the high society of Montmartre isolated forever the bohemian youth of the left bank of the Seine, the poor art students, the anarchists, which was the beginning of the bourgeoisie's spatial division of classes through the urban plan.[8] The fabulous urban life of leisure for Cézanne and Manet was based on a spatial plan that separated the rich from the poor and prevented revolutions. Art is not merely a reflection of one's own ideology; the process of making art involves how the artist in a given situation represents the world in relation to himself. In a specific spatial (French impressionist urban life and Haussmann's renovation of Paris) and historical conditions (France between 1848 and 1871), the bourgeoisie and the Petit Bourgeoisie, in order to differentiate themselves from the other classes, consciously (partly reflected the conditions of their own class, but not necessarily) created a class for themselves. This explains the relationship between artists' conscious aesthetic creation and social practice.

3. The United States: Artistic Subjectivity in the Culture of the Cold War

It was not until the 1940s and 60s that the subjectivity of modern art in the West was finalized by Clement Greenberg, who established the “resistant subject”. Grant Kester, in Conversation Pieces, continued Bourdieu's view: “The only refuge for the artist disenchanted with socialism and disgusted by capitalism was to withdraw into a resistant subjectivity and to reject ‘comprehensibility’ entirely. ”[9] Kester's critique is socio-historically conditioned by his rejection of the European subject of modern art, thereby establishing a set of anti-(European) elitist modes of artistic production, he says:

This receptive openness to the world runs throughout avant-garde discourse, in Bell’s and Fry’s rejection of normalizing representational conventions, in Greenberg's assault on the clichés of kitsch, and in Fried's criticism of theatrical art that shamelessly importunes the viewer. In each case, however, it is assumed that this openness can be purchased only at the expense of an indifference to (or assault on) the viewer and his or her associations and prior experiences. Once the work interacts with the viewer through a shared language, familiar visual conventions, or even an implicit acknowledgment of the viewer's physical presence in the same space, it sets off down the slippery slope of violence and negation.[10]

For Kester, European artistic autonomy precluded the possibility of dialogue, and any work with an intent and function that could be comprehended or interpreted was a popular and despicable object. However, the “dialogical framework” he proposes exempts the work of art, freeing the artist from aesthetic form and ethical imperatives, and transforming speaking for the people into letting the people speak for themselves, without guaranteeing the validity of the people's speech or making political judgments about letting “what kind” of people to speak. Artists are not responsible for the form of their work, because it is the result of people's participation or continuous dialog. In this way, the connotation of social art as a voice for the underprivileged (workers, students, the poor and the needy) is canceled out, and the people become nothing more than a mass of individuals.

Kester's “democratization of aesthetics” has its origins in the continuation of the cultural Cold War ideology. Since World War II, the U.S. has been promoting abstract expressionism to Europe through the CIA and the Rockefeller Center in an attempt to move the center of art from Paris to New York. “Culture is the propaganda of the Cold War,” and “Abstract Expressionism is the weapon of the Cold War,” are the opening statements of many contemporary art textbooks. Artists such as Jackson Pollock are often derided as Cold War warriors, as Louis Menand noted in his 2005 “Unpopular Front” article in The New Yorker. It has long been no secret that the Cold War was a cultural struggle. Even the Fulbright Program, which was established in 1946 to play the same role as the CIA, was a product of Cold War thinking. Eva Cockcroft's article makes it even clearer.[11] American cultural propaganda was aimed at the elite abroad, left-wing or left-connected, or sympathetic to the Soviets or Maoists, so that they would still maintain an avant-garde left-wing ideology, but only as long as they were anti-Communist, which was America's post-war global strategy.

The feeling that art has nothing to do with the CIA or Rockefeller Center happens to be an illusion that art maintains neutrality to stay clean. Foundations, universities, and cultural centers are important tools to actively compete with the European and Chinese left-wing and to seize its own artistic positions. In addition to the active promotion of their own political aesthetics, on the other hand, the semi-colonial “embassy art” was used as a cultural weapon in the Cold War.

Taiwan's naïve painter Hung Tung is the best example. Hung Tung's first solo exhibition was at the Lincoln Center of the U.S. Information Service in Taipei (1976), and in 1987, the The Artist magazine at the American Cultural Centre in Taipei held a retrospective after his death. It was only after the retrospective that the Tainan Cultural Center collected three of his paintings. In total, Hung Tung painted more than three hundred paintings in his life, and eventually died in poverty. His first solo exhibition was organized by the American Cultural Center, and his retrospective exhibition after his death was also organized by the American Cultural Center. Under the strong promotion of the United States, it seems that Taiwan only became aware of the existence of this figure, and then the Tainan Cultural Center collected him, which is nothing more ironic than the fact that something native to Taiwan was “invented” by the United States. Another example is the Iowa International Writing Program, which many early Taiwanese literary figures and artists attended, such as Chen Ying-chen, Lin Hwai-min, Chiang Hsun, Kao Hsin-kiang, Ya Xian, Tai Ching-nung, Xiang-yang, Shang Qin , Wei Tien-chung, Guan Guan, Yao Yi-wei, Yin Yun-peng, Ji Ji, Ge Chu, and so on. This shaped the ideology of early Taiwanese literature and art, bringing back to Taiwan the ideology promoted by the United States, and is the reason why the literary tradition of modernism in Taiwan is so close to American values. Lin Huaimin on modern dance is the best example. The same is true for the mainland, such as the art in Beijing's embassy district around the 1980s, like Ai Weiwei's “Black Book” and the subsequent 1989 Modern Art Exhibition, which started in the embassy district. The history of art in both Taiwan and mainland China has been influenced by the economic and cultural strategy of the United States, which was rolled out under the Cold War mentality.

If the European historical avant-garde was concerned with how to sew up the rupture between elite art and daily life, how to break through the boundary between high and low art, and how to actively challenge the monopoly of art production by art institutions, and Dada, Surrealism, and the Fluxus of the 1970s all had this characteristic, which demonstrated the reflection and resistance to the gradual specialization and institutionalization of modern art, then what the United States needed in the post-war period was not to challenge elite art and art institutions, which it did not yet have, which explains why Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art seemed so distinct from each other, yet the two trends did not clash in breaking new ground for American political forms of aesthetics. At the same time, the United States has continued to build large art museums and institutions, such as MoMA, to increase its influence on culture and the arts. We might say that the United States ended rather than inherited the European historical avant-garde, and that the United States replaced the European historical avant-garde and the intellectual critique of the system with the post-modern, Pop Art-toned, commercial mechanisms of giant art institutions and commercial galleries.[12]