2021

“A Proposal for Sheng Project” was jointly initiated by the Institute of Contemporary Art and Social Thought at the China Academy of Art and the Long March Project in 2015. It focuses on the artistic career of Mr. Zheng Shengtian, a prominent figure in contemporary Chinese art for over 70 years. The aim is not to provide a personal retrospective of Zheng Shengtian but to attempt a reinterpretation of 20th-century Chinese art history through his life and art experiences spanning more than half a century, thereby revitalizing our historical sensibilities of Chinese art and society, and bringing possibilities back to history.

Zheng Shengtian was born in 1938 in a Confucian temple in his hometown in Henan province. With the character “Sheng (圣)” meaning sage, his given name implies the blessings received from the wise upon his birth. During the Cultural Revolution, Zheng Shengtian changed his given name with “Sheng (胜)” meaning triumph this time, reflecting his belief that man can overcome any obstacle. As an art educator at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts, he taught students who became the vanguard of the ’85 New Wave Art Movement. Zheng Shengtian himself was a pivotal supporter of the movement in Chinese art and played a significant role in shaping contemporary art in China. In the 1980s, he actively promoted experimentation and exploration among young artists, enabling them to sustain and develop their artistic potential. Zheng Shengtian is an exceptionally sophisticated figure in the history of Chinese contemporary art. For one thing, being brimful of energy and curiosity, he delves into numerous facets of the art world. He is not only an artist but also an educator, scholar, curator, writer, and among the earliest promoters and founders of art magazines, art galleries, art exhibitions, art foundations, and other contemporary art institutions in China. For another thing, from the inception of the People’s Republic of China to the present day, Zheng Shengtian’s narrative weaves through the tapestry of contemporary Chinese art history. Through the 1950s and the Cultural Revolution, into the dawn of a new era and the onset of the new century, finally at home and abroad, Zheng Shengtian has consistently been present at numerous crucial junctures in Chinese art history. Starting from Zheng Shengtian’s personal life, we can explore the meaning, value, and aspirations of art amidst varied historical and cultural landscapes. Since the 20th century, China’s revolution and development have been inseparable from the global historical process. Art is the most sensitive cultural barometer that bridges the domestic dynamics and overseas transformations. In the later stage of his extensive artistic journey, Zheng Shengtian has resided overseas, profoundly engaging in Chinese art’s evolution and identity shaping on the global stage. Throughout the past three decades, he has witnessed many events, movements, and paradigm shifts within the international art scene. Thus, we believe that “Sheng Project” not only stands out as a remarkable chapter in the 80-year narrative of Chinese art but also holds significant research value for reflections and historical criticism of contemporary global art.

“Sheng Project” is the brainchild of Zheng Shengtian. He coined the word “Project” (作业) to refer to both his life journey and artistic career, and “Sheng” is what friends call him. He has established an online open-source database and the website is shengproject.com. From photos and sketches to letters, manuscripts, briefs, journals, magazines, and painting albums, this treasure house unveils a narrative rooted in personal life experiences and waiting to be explored.

I

“My life is like a Zócalo, bustling with people coming and going,” said Zheng Shengtian. For over eight decades, his engagements, observations, reactions, and endeavors in this lively square have gifted us with ample sources for research. His life mirrors a meticulously crafted narrative of history, offering a window into the complexities, uncertainties, and interactions in the intricate story of Chinese art and social development. Through him, we can discern myriad hidden reefs, undercurrents, and the perpetual aggregation of energy generated from the long history.

The first proposal for “Sheng Project” involved organizing an exhibition at the Long March Space. More precisely, it was not a conventional exhibition proposal but an action of “occupation.” The fabulous life story of Zheng Shengtian, an artist with multiple identities, dominated the discourse, exhibition, and commercial spaces in the Long March Space. The proposal of the “occupation” consisted of seven units. Unit one, “My Life as a Zócalo,” unfolds as a century plaza shaped by the river of life. It occupies the main exhibition hall of the Long March Space, seamlessly integrating multiple images of the square, river, and maze. Zheng Shengtian’s observations, reflections, and practices discovered along his artistic journey are chronologically displayed. The duo of personal life and social history creates their interactive, reflective, or confrontational dynamics, shaping the twists, turns, continuities, and revelations of the river of time. Life encounters are like rocks, big or small, colliding to create the spindrift of life in the river of time. Zheng Shengtian’s ongoing project, launched in 2008, to create portraits of the 100 people he has been coming across in his life, is placed in this intricate “plaza-river-maze” layout. The portraits serve as milestones where life journey and art history intersected. The paintings on the walls and the archives exhibit in the space formed a captivating interplay, prompting reflection on the multitude of diverging paths and diverse spaces that emerge between artistic creation and historical reality, as well as between social history and individual life.

Unit two, “YISHU≠ART”, presents a conceptual debate. It occupies the conference room of the Long March Space. We take Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art as the discourse background, providing a space for conceptual debate between Yishu and Art. Unit three, “ASK SHENG,” creates an online club where fans could gather and talk to Sheng. It occupies the VIP room of the Long March Space. Unit four, “Crossing the Pacific,” an ongoing plan, occupies the co-working area of the Long March Space. Unit five, “Modern vs. Revolutionary,” aims to explore two camps of modernism in the art history of the New China (after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949), occupying the gallery of the Long March Space. Unit six, “Sheng Classroom,” is a pop-up classroom free from “academicism.” It occupies the project exhibition hall of the Long March Space. Lastly, unit seven, Jiangnan, seeks to evoke a sense of attachment or a reluctance to discard the lyricism excluded by contemporary art. It is housed within the inner exhibition hall of the Long March Space.

After multiple rounds of careful discussions, we opted to table the one-time action of “occupation” and shifted our focus to run a marathon of research and deliberation. Our objective was to nurture the continuous development of this proposal and to take a deep dive into the historical context, consciousness of problems, and discourse position. We also aspired to embrace a more inclusive approach, inviting more friends and colleagues to join us. Thus, we planned to compile several years’ worth of ideas, findings, speculations, and perplexities related to this case into a book that was presented as a curatorial proposal to peers in the domestic and international art community, as well as to Zheng Shengtian himself.

II

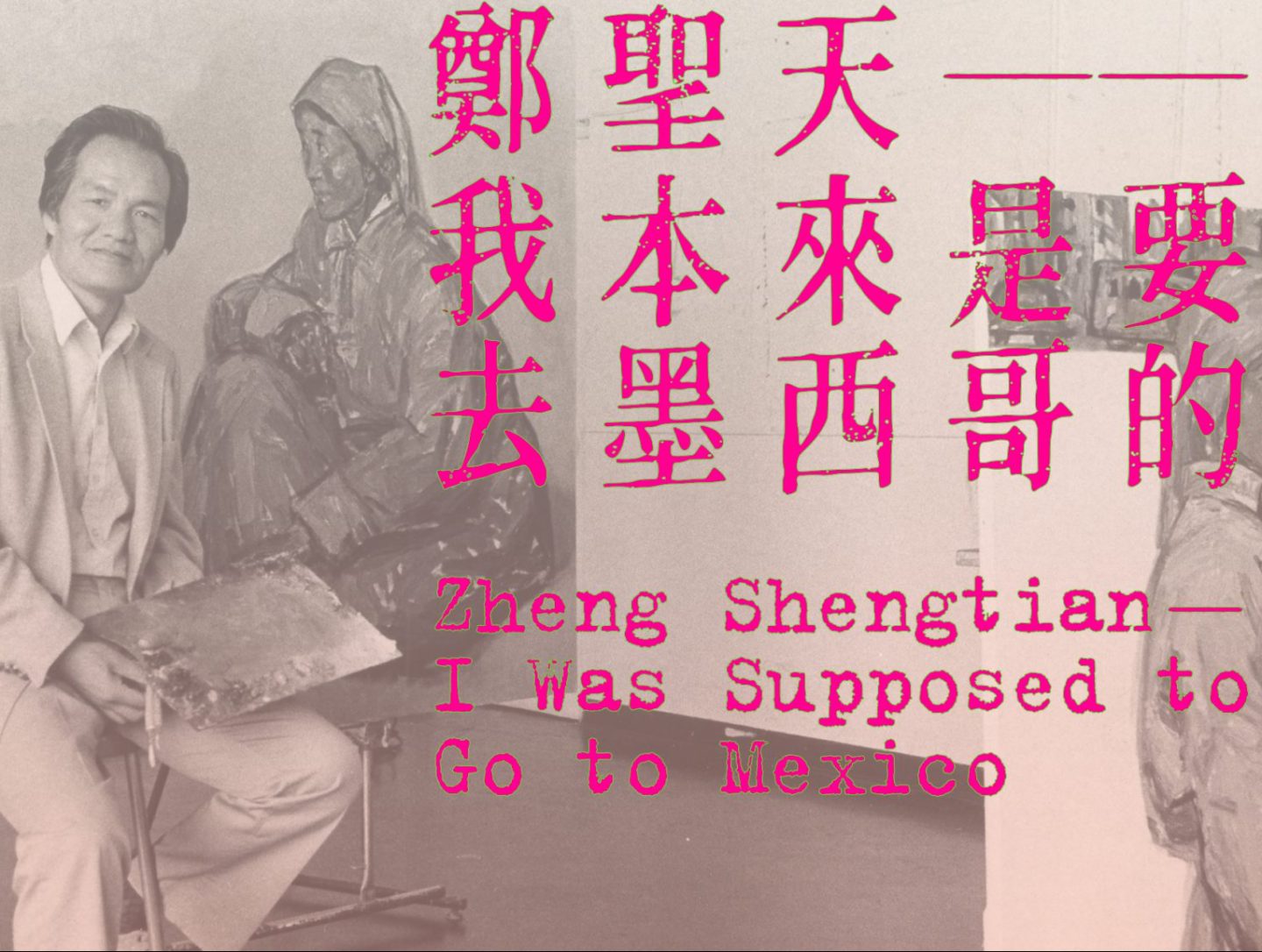

A Proposal for Sheng Project comprised three volumes: I Was Supposed to Go to Mexico, YISHU≠ART, and Reader.

Sheng Reader included 27 articles written by Chinese and foreign authors over the past century. Spanning various fields such as art, literature, philosophy, and politics, these writings reflected different periods and contexts and offered a crucial reference for the conceptual history of the proposal. Sheng Reader attempted to develop a framework to reflect on the clash between realism and modernism in various historical contexts in China and beyond, and explore the power dynamics among art, society, and politics in shaping “socialist literature and art.” Furthermore, it presented multiple perspectives to reevaluate the complex relationships between the avant-garde and revolution, revolution and internationalism, internationalism and nation, nation and politics, politics and art, as well as art and revolution.

YISHU≠ART included paintings by Zheng Shengtian spanning different periods. While living in Vancouver in 2002, Zheng Shengtian established an English journal focused on contemporary Chinese art, which he named Yishu. Zheng Shengtian highlighted the differences between the Chinese term Yishu and its English equivalent Art. Through this journal, he endeavored to illustrate the untranslatability inherent in Chinese and Western cultures and art. Meanwhile, his paintings, which span over sixty years, offered another perspective on art. We endeavored to go beyond traditional concepts of painter and artwork in comprehending Zheng Shengtian’s journey in painting. Our quest was to unravel what painting truly means to Zheng Shengtian. Hence, this is not merely a catalog of artworks. Whether they were sketches from his time in a studio, propaganda paintings or portraits of leaders during the Cultural Revolution, or even passionate formal experiments during his visit to the United States in the 1980s, or casually sketched landscapes in the suburbs of Vancouver...everything stood on equal footing. Because, for Zheng Shengtian, these paintings constituted another album of his life’s narrative. Regardless of their artistic merits, they were postcards he sent to himself at different junctures of his life journey.

“I was supposed to go to Mexico,” said Zheng Shengtian in the first proposal workshop of “Sheng Project,” reminiscing about his inaugural journey abroad. This ordinary remark struck as profound over forty years later, prompting us to make it the cornerstone of our proposal. As a pivotal figure in fostering dialog between Chinese contemporary art and the Western art world since the 1980s, Zheng Shengtian had initially set his sights on Mexico. This revelation bore profound historical resonance, inviting us to delve into its significance throughout the years. How should we interpret this message? How should we grasp its intricate historical implications? Born in 1938, Zheng Shengtian has witnessed various epochs of Chinese social and art history and ventured into different realms of artistic expression. His artistic journey has brought forth “two modernisms” and “two internationalisms.” Throughout his life journey, the theme “I Was Supposed to Go to Mexico” has remained subtly discernible, a constant presence amidst changing times.

Based on the observation of the “two internationalisms” in Zheng Shengtian, this proposal was structured into two acts, namely “Internationalism: Horizon of the World” and “Another Internationalism: I Was Supposed to Go to Mexico.” It concluded with an epilogue introducing significant events of 1938, which indicated that this remarkable year was where Sheng’s personal story begins. Through the lens of Zheng Shengtian’s experiences, the narrative delved into a series of historical events we observed. Each unit commenced with the “Proposer’s Voice” to offer the observer’s perspective, followed by relevant historical records, concluding with Zheng Shengtian’s writings, thereby creating a multi-dimensional dialogue.

The first act began with Zheng Shengtian’s “Grand Tour Around the World” from 1981 to 1983, followed by the narrative in two phases: the “’85 New Wave Art Movement” of the 1980s and “Toward the World: Two Modernisms” after the 1990s. In 1981, appointed by the Chinese Ministry of Culture as a leading figure in the post-Cultural Revolution art scene, Zheng Shengtian embarked on a two-year study trip to the United States. During this period, he not only witnessed the novel and diverse artistic landscape of the United States but also traveled to over a dozen European countries, including the former Soviet Union, thirstily absorbing the development and changes in Western art. The tour was crucial for Zheng Shengtian’s subsequent artistic journey. Upon returning to China, he disseminated his knowledge through lectures, exhibitions, and magazine publications, profoundly influencing numerous emerging artists.

In the section “’85 New Wave Art Movement,” we sought to shed new light on this movement through Zheng Shengtian’s experiences and endeavors in the latter half of the 1980s. The debate sparked by the 1985 graduation exhibition and defense of the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts offered a glimpse into the art world’s experience and expression of the polarized social reality at that time. More importantly, this debate presented another way of thinking about the relationship between individuality and style, as well as art and reality, during that period. Around 1985, Zao Wou-Ki, Roman H. Verostko, Robert Rauschenberg, and Maryn Varbanov made their debut in the Chinese art scene, heralding not only the “Second Coming” of modernism but also the simultaneous introduction of Western art of the first and second halves of the 20th century. This coincided with the decline of realism in Chinese art after the Cultural Revolution, bringing new stimuli to the Chinese art world. With tremendous enthusiasm and courage, a cohort of young artists pioneered new realms of artistic expression, reshaping the contemporary art scene in China. More than thirty years later, we attempted to analyze whether the so-called “’85 New Wave Art Movement” was a resurgence of the avant-garde or a revival of modernism, and whether an art movement detached from its social context could still be considered avant-garde.

“Toward the World: Two Modernisms” introduced Zheng Shengtian’s artistic experiences overseas after the 1990s. To name a few, he established the bilingual Chinese Art Newsletter (later renamed Art China Newsletter); contributed to curating the exhibition named “When China Meets the West” and participated in the exhibition “I Don’t Want to Play Cards with Cézanne;” contributed to the organization of the China Art Exposition and its collaboration with Art Asia Hong Kong; participated in the establishment and management of the Chinese art foundations and galleries; co-curated the “Jiangnan Project” and established the Vancouver International Centre for Contemporary Asian Art (Centre A); facilitated the collective exhibition of Chinese artists at the 48th Venice Biennale and the visit of the curatorial team of Documenta 11 to China; continued to host the radio program Contemporary Art Landscape; co-founded the art journal Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art; co-curated the “Techniques of the Visible” of the 2004 Shanghai Biennale and the “Shanghai Modern 1919–1945;” facilitated the establishment of the Institute of Asian Art at the Vancouver Art Gallery...Zheng Shengtian has dedicated himself to fostering the exchange between Chinese art and the international art scenes, thereby propelling Chinese art onto the global stage. This unit focused on two thematic exhibitions that he curated in the new century, namely “Shanghai Modern 1919–1945” (Munich) as well as “Art and China’s Revolution” (New York). For one thing, the double variation of “revolutionary and modern” in 20th-century Chinese history and art was explored. We also attempted to interpret the complex implications of the double variation within the historical frameworks of colonial/post-colonial and revolutionary/post-revolutionary eras, as well as its insights into contemporary Chinese and international art.

The second act, “Another Internationalism: I Was Supposed to Go to Mexico,” opened with the “Dream about Mexico” of Zheng Shengtian’s generation, attempting to unearth the diverse and in-depth explorations during the self-development of socialist art in the 1950s and 1960s. These explorations revealed “another type of internationalism or modernism” represented by Mexican murals at that time. In 2015, Zheng Shengtian launched a new research project called “Socialist Modernism,” with the most significant part being the themed exhibition “Winds from Fusang: Mexico and China in the Twentieth Century.” In 2017, at the age of 79, Zheng Shengtian and artists such as Sun Jingbo collectively created a large narrative mural named Winds from Fusang. Centering on the 20th-century Sino-Mexican artistic exchange, the mural reviewed the history of artistic exchanges among China, Mexico, and other Latin American countries against the backdrop of the World Revolution and the Third World Movement. Serving as a response to the “Dream about Mexico” cherished by Chinese artists six decades prior and a tribute to the artistic spirit of internationalism of that era, this artwork debuted alongside the exhibition at the USC Pacific Asia Museum and toured to the Museo Mural Diego Rivera the following year. Through this endeavor, a journey was undertaken to rediscover the diverse and dynamic artistic landscape of sixty years ago, to reinterpret “socialist internationalism” connected to a concept, vision, and emotion, to reassess the dialectics of nationalism and internationalism, artistic revolution and revolutionary art, as well as realism and modernism, and to understand the tremendous historical potential they once possessed in the context of socialist literature and art.

Finally, we need to turn our attention to 1938, when Zheng Shengtian was born. That year, Wuhan, the capital of Hubei Province in China, emerged as a significant battleground in the Far East during the Anti-Fascist War. It not only gathered diverse anti-Japanese forces from across China but also attracted a large number of leftist internationalist fighters. Figures like Joris Ivens, Robert Capa, and Norman Bethune joined the International Brigades, relocating from Madrid to Wuhan. Additionally, champions of internationalism such as Edgar Snow, David & Isabel Crook, Anna Louise Strong, and Agnes Smedley arrived in China, fervently supporting the nation’s anti-fascist cause. Meanwhile, significant and profound changes occurred in the European art world. Amidst the ideological struggles between revolution and freedom, artistic revolution and revolutionary art, and even between Trotskyists and Stalinists, the Surrealist group experienced a split in 1938, and the international avant-garde cultural and artistic movement driven by left-wing ideologies gradually came to an end. The war-torn Wuhan stood as the ultimate culmination of internationalism after Madrid. These pivotal events, comprising a dialectical historical tableau, marked the epilogue of this proposal and heralded the beginning of Zheng Shengtian’s life narrative. Thus, we entitled this chapter “1938: The Last Internationalism.”

III

This proposal has received wholehearted support from Mr. Zheng Shengtian, who generously shared all his materials and attended the proposal workshops twice. He also participated in the research and brainstorming of the project multiple times, providing valuable insights into the specific content and structure of this proposal. Even in his eighties, Mr. Zheng has remained remarkably enthusiastic about his work and initiatives. The ongoing updates to “Sheng Project” inspire and encourage our younger generations.

Over the past six years, this project has also received care and support from numerous friends. Three proposal workshops were conducted, where friends from diverse fields, such as art, literature, history, politics, and ideology, both domestically and internationally, were invited to share resources and delve into topics together. These discussions sparked myriad brilliant insights, offering invaluable enlightenment. From the outset, these dialogues aided in clarifying the original aspiration of the project: avoiding a personal retrospective, avoiding attempt to restore historical scenes by studying archives, and avoiding conduct comparative studies between individual life history and social development history, as well as averting deification, projection, and historical determinism. It can be said that “A Proposal for Sheng Project” is presented in its current structure as the result of the collective wisdom of all participants at all stages, for which we are deeply grateful. Therefore, we have selected the highlights of the three workshops and included them in the proposal.

“I Was Supposed to Go to Mexico: A Proposal for Sheng Project” aims to bridge the three fragmented thirty-year periods in 20th-century Chinese history. Based on the rich assets of Zheng Shengtian’s life history spanning over 80 years, it portrays a river of life that traverses multiple art worlds, unfolds a bustling century square, and sketches an intricate maze of destiny. The depiction of the river, square, and maze not only explores the untold possibilities and potential in Chinese art history but also takes a deep dive into the encounters, struggles, attachments, and creative endeavors spanning several generations of personal life histories.

We look forward to inviting more friends to get involved through this proposal, to perceive, feel, and engage with an inclusive historical narrative from personal life experiences. By collaborating across generations, we aspire to foster a deeper understanding and emotional re-connection among different age groups, allowing forgotten and fragmented memories and narratives to resonate again with contemporary life. We believe that only in the resonance of body and mind, and amidst the sparks generated from the collision between self and events, can the past be enlightened; only by recreating a scene can we confront history—only by becoming a part of its vast can one master the past.

Translated by Ma Yanxin

“A Proposal for Sheng Project” was jointly initiated by the Institute of Contemporary Art and Social Thought at the China Academy of Art and the Long March Project in 2015. It focuses on the artistic career of Mr. Zheng Shengtian, a prominent figure in contemporary Chinese art for over 70 years. The aim is not to provide a personal retrospective of Zheng Shengtian but to attempt a reinterpretation of 20th-century Chinese art history through his life and art experiences spanning more than half a century, thereby revitalizing our historical sensibilities of Chinese art and society, and bringing possibilities back to history.

Zheng Shengtian was born in 1938 in a Confucian temple in his hometown in Henan province. With the character “Sheng (圣)” meaning sage, his given name implies the blessings received from the wise upon his birth. During the Cultural Revolution, Zheng Shengtian changed his given name with “Sheng (胜)” meaning triumph this time, reflecting his belief that man can overcome any obstacle. As an art educator at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts, he taught students who became the vanguard of the ’85 New Wave Art Movement. Zheng Shengtian himself was a pivotal supporter of the movement in Chinese art and played a significant role in shaping contemporary art in China. In the 1980s, he actively promoted experimentation and exploration among young artists, enabling them to sustain and develop their artistic potential. Zheng Shengtian is an exceptionally sophisticated figure in the history of Chinese contemporary art. For one thing, being brimful of energy and curiosity, he delves into numerous facets of the art world. He is not only an artist but also an educator, scholar, curator, writer, and among the earliest promoters and founders of art magazines, art galleries, art exhibitions, art foundations, and other contemporary art institutions in China. For another thing, from the inception of the People’s Republic of China to the present day, Zheng Shengtian’s narrative weaves through the tapestry of contemporary Chinese art history. Through the 1950s and the Cultural Revolution, into the dawn of a new era and the onset of the new century, finally at home and abroad, Zheng Shengtian has consistently been present at numerous crucial junctures in Chinese art history. Starting from Zheng Shengtian’s personal life, we can explore the meaning, value, and aspirations of art amidst varied historical and cultural landscapes. Since the 20th century, China’s revolution and development have been inseparable from the global historical process. Art is the most sensitive cultural barometer that bridges the domestic dynamics and overseas transformations. In the later stage of his extensive artistic journey, Zheng Shengtian has resided overseas, profoundly engaging in Chinese art’s evolution and identity shaping on the global stage. Throughout the past three decades, he has witnessed many events, movements, and paradigm shifts within the international art scene. Thus, we believe that “Sheng Project” not only stands out as a remarkable chapter in the 80-year narrative of Chinese art but also holds significant research value for reflections and historical criticism of contemporary global art.

“Sheng Project” is the brainchild of Zheng Shengtian. He coined the word “Project” (作业) to refer to both his life journey and artistic career, and “Sheng” is what friends call him. He has established an online open-source database and the website is shengproject.com. From photos and sketches to letters, manuscripts, briefs, journals, magazines, and painting albums, this treasure house unveils a narrative rooted in personal life experiences and waiting to be explored.

I

“My life is like a Zócalo, bustling with people coming and going,” said Zheng Shengtian. For over eight decades, his engagements, observations, reactions, and endeavors in this lively square have gifted us with ample sources for research. His life mirrors a meticulously crafted narrative of history, offering a window into the complexities, uncertainties, and interactions in the intricate story of Chinese art and social development. Through him, we can discern myriad hidden reefs, undercurrents, and the perpetual aggregation of energy generated from the long history.

The first proposal for “Sheng Project” involved organizing an exhibition at the Long March Space. More precisely, it was not a conventional exhibition proposal but an action of “occupation.” The fabulous life story of Zheng Shengtian, an artist with multiple identities, dominated the discourse, exhibition, and commercial spaces in the Long March Space. The proposal of the “occupation” consisted of seven units. Unit one, “My Life as a Zócalo,” unfolds as a century plaza shaped by the river of life. It occupies the main exhibition hall of the Long March Space, seamlessly integrating multiple images of the square, river, and maze. Zheng Shengtian’s observations, reflections, and practices discovered along his artistic journey are chronologically displayed. The duo of personal life and social history creates their interactive, reflective, or confrontational dynamics, shaping the twists, turns, continuities, and revelations of the river of time. Life encounters are like rocks, big or small, colliding to create the spindrift of life in the river of time. Zheng Shengtian’s ongoing project, launched in 2008, to create portraits of the 100 people he has been coming across in his life, is placed in this intricate “plaza-river-maze” layout. The portraits serve as milestones where life journey and art history intersected. The paintings on the walls and the archives exhibit in the space formed a captivating interplay, prompting reflection on the multitude of diverging paths and diverse spaces that emerge between artistic creation and historical reality, as well as between social history and individual life.

Unit two, “YISHU≠ART”, presents a conceptual debate. It occupies the conference room of the Long March Space. We take Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art as the discourse background, providing a space for conceptual debate between Yishu and Art. Unit three, “ASK SHENG,” creates an online club where fans could gather and talk to Sheng. It occupies the VIP room of the Long March Space. Unit four, “Crossing the Pacific,” an ongoing plan, occupies the co-working area of the Long March Space. Unit five, “Modern vs. Revolutionary,” aims to explore two camps of modernism in the art history of the New China (after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949), occupying the gallery of the Long March Space. Unit six, “Sheng Classroom,” is a pop-up classroom free from “academicism.” It occupies the project exhibition hall of the Long March Space. Lastly, unit seven, Jiangnan, seeks to evoke a sense of attachment or a reluctance to discard the lyricism excluded by contemporary art. It is housed within the inner exhibition hall of the Long March Space.

After multiple rounds of careful discussions, we opted to table the one-time action of “occupation” and shifted our focus to run a marathon of research and deliberation. Our objective was to nurture the continuous development of this proposal and to take a deep dive into the historical context, consciousness of problems, and discourse position. We also aspired to embrace a more inclusive approach, inviting more friends and colleagues to join us. Thus, we planned to compile several years’ worth of ideas, findings, speculations, and perplexities related to this case into a book that was presented as a curatorial proposal to peers in the domestic and international art community, as well as to Zheng Shengtian himself.

II

A Proposal for Sheng Project comprised three volumes: I Was Supposed to Go to Mexico, YISHU≠ART, and Reader.

Sheng Reader included 27 articles written by Chinese and foreign authors over the past century. Spanning various fields such as art, literature, philosophy, and politics, these writings reflected different periods and contexts and offered a crucial reference for the conceptual history of the proposal. Sheng Reader attempted to develop a framework to reflect on the clash between realism and modernism in various historical contexts in China and beyond, and explore the power dynamics among art, society, and politics in shaping “socialist literature and art.” Furthermore, it presented multiple perspectives to reevaluate the complex relationships between the avant-garde and revolution, revolution and internationalism, internationalism and nation, nation and politics, politics and art, as well as art and revolution.

YISHU≠ART included paintings by Zheng Shengtian spanning different periods. While living in Vancouver in 2002, Zheng Shengtian established an English journal focused on contemporary Chinese art, which he named Yishu. Zheng Shengtian highlighted the differences between the Chinese term Yishu and its English equivalent Art. Through this journal, he endeavored to illustrate the untranslatability inherent in Chinese and Western cultures and art. Meanwhile, his paintings, which span over sixty years, offered another perspective on art. We endeavored to go beyond traditional concepts of painter and artwork in comprehending Zheng Shengtian’s journey in painting. Our quest was to unravel what painting truly means to Zheng Shengtian. Hence, this is not merely a catalog of artworks. Whether they were sketches from his time in a studio, propaganda paintings or portraits of leaders during the Cultural Revolution, or even passionate formal experiments during his visit to the United States in the 1980s, or casually sketched landscapes in the suburbs of Vancouver...everything stood on equal footing. Because, for Zheng Shengtian, these paintings constituted another album of his life’s narrative. Regardless of their artistic merits, they were postcards he sent to himself at different junctures of his life journey.

“I was supposed to go to Mexico,” said Zheng Shengtian in the first proposal workshop of “Sheng Project,” reminiscing about his inaugural journey abroad. This ordinary remark struck as profound over forty years later, prompting us to make it the cornerstone of our proposal. As a pivotal figure in fostering dialog between Chinese contemporary art and the Western art world since the 1980s, Zheng Shengtian had initially set his sights on Mexico. This revelation bore profound historical resonance, inviting us to delve into its significance throughout the years. How should we interpret this message? How should we grasp its intricate historical implications? Born in 1938, Zheng Shengtian has witnessed various epochs of Chinese social and art history and ventured into different realms of artistic expression. His artistic journey has brought forth “two modernisms” and “two internationalisms.” Throughout his life journey, the theme “I Was Supposed to Go to Mexico” has remained subtly discernible, a constant presence amidst changing times.

Based on the observation of the “two internationalisms” in Zheng Shengtian, this proposal was structured into two acts, namely “Internationalism: Horizon of the World” and “Another Internationalism: I Was Supposed to Go to Mexico.” It concluded with an epilogue introducing significant events of 1938, which indicated that this remarkable year was where Sheng’s personal story begins. Through the lens of Zheng Shengtian’s experiences, the narrative delved into a series of historical events we observed. Each unit commenced with the “Proposer’s Voice” to offer the observer’s perspective, followed by relevant historical records, concluding with Zheng Shengtian’s writings, thereby creating a multi-dimensional dialogue.

The first act began with Zheng Shengtian’s “Grand Tour Around the World” from 1981 to 1983, followed by the narrative in two phases: the “’85 New Wave Art Movement” of the 1980s and “Toward the World: Two Modernisms” after the 1990s. In 1981, appointed by the Chinese Ministry of Culture as a leading figure in the post-Cultural Revolution art scene, Zheng Shengtian embarked on a two-year study trip to the United States. During this period, he not only witnessed the novel and diverse artistic landscape of the United States but also traveled to over a dozen European countries, including the former Soviet Union, thirstily absorbing the development and changes in Western art. The tour was crucial for Zheng Shengtian’s subsequent artistic journey. Upon returning to China, he disseminated his knowledge through lectures, exhibitions, and magazine publications, profoundly influencing numerous emerging artists.

In the section “’85 New Wave Art Movement,” we sought to shed new light on this movement through Zheng Shengtian’s experiences and endeavors in the latter half of the 1980s. The debate sparked by the 1985 graduation exhibition and defense of the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts offered a glimpse into the art world’s experience and expression of the polarized social reality at that time. More importantly, this debate presented another way of thinking about the relationship between individuality and style, as well as art and reality, during that period. Around 1985, Zao Wou-Ki, Roman H. Verostko, Robert Rauschenberg, and Maryn Varbanov made their debut in the Chinese art scene, heralding not only the “Second Coming” of modernism but also the simultaneous introduction of Western art of the first and second halves of the 20th century. This coincided with the decline of realism in Chinese art after the Cultural Revolution, bringing new stimuli to the Chinese art world. With tremendous enthusiasm and courage, a cohort of young artists pioneered new realms of artistic expression, reshaping the contemporary art scene in China. More than thirty years later, we attempted to analyze whether the so-called “’85 New Wave Art Movement” was a resurgence of the avant-garde or a revival of modernism, and whether an art movement detached from its social context could still be considered avant-garde.

“Toward the World: Two Modernisms” introduced Zheng Shengtian’s artistic experiences overseas after the 1990s. To name a few, he established the bilingual Chinese Art Newsletter (later renamed Art China Newsletter); contributed to curating the exhibition named “When China Meets the West” and participated in the exhibition “I Don’t Want to Play Cards with Cézanne;” contributed to the organization of the China Art Exposition and its collaboration with Art Asia Hong Kong; participated in the establishment and management of the Chinese art foundations and galleries; co-curated the “Jiangnan Project” and established the Vancouver International Centre for Contemporary Asian Art (Centre A); facilitated the collective exhibition of Chinese artists at the 48th Venice Biennale and the visit of the curatorial team of Documenta 11 to China; continued to host the radio program Contemporary Art Landscape; co-founded the art journal Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art; co-curated the “Techniques of the Visible” of the 2004 Shanghai Biennale and the “Shanghai Modern 1919–1945;” facilitated the establishment of the Institute of Asian Art at the Vancouver Art Gallery...Zheng Shengtian has dedicated himself to fostering the exchange between Chinese art and the international art scenes, thereby propelling Chinese art onto the global stage. This unit focused on two thematic exhibitions that he curated in the new century, namely “Shanghai Modern 1919–1945” (Munich) as well as “Art and China’s Revolution” (New York). For one thing, the double variation of “revolutionary and modern” in 20th-century Chinese history and art was explored. We also attempted to interpret the complex implications of the double variation within the historical frameworks of colonial/post-colonial and revolutionary/post-revolutionary eras, as well as its insights into contemporary Chinese and international art.

The second act, “Another Internationalism: I Was Supposed to Go to Mexico,” opened with the “Dream about Mexico” of Zheng Shengtian’s generation, attempting to unearth the diverse and in-depth explorations during the self-development of socialist art in the 1950s and 1960s. These explorations revealed “another type of internationalism or modernism” represented by Mexican murals at that time. In 2015, Zheng Shengtian launched a new research project called “Socialist Modernism,” with the most significant part being the themed exhibition “Winds from Fusang: Mexico and China in the Twentieth Century.” In 2017, at the age of 79, Zheng Shengtian and artists such as Sun Jingbo collectively created a large narrative mural named Winds from Fusang. Centering on the 20th-century Sino-Mexican artistic exchange, the mural reviewed the history of artistic exchanges among China, Mexico, and other Latin American countries against the backdrop of the World Revolution and the Third World Movement. Serving as a response to the “Dream about Mexico” cherished by Chinese artists six decades prior and a tribute to the artistic spirit of internationalism of that era, this artwork debuted alongside the exhibition at the USC Pacific Asia Museum and toured to the Museo Mural Diego Rivera the following year. Through this endeavor, a journey was undertaken to rediscover the diverse and dynamic artistic landscape of sixty years ago, to reinterpret “socialist internationalism” connected to a concept, vision, and emotion, to reassess the dialectics of nationalism and internationalism, artistic revolution and revolutionary art, as well as realism and modernism, and to understand the tremendous historical potential they once possessed in the context of socialist literature and art.

Finally, we need to turn our attention to 1938, when Zheng Shengtian was born. That year, Wuhan, the capital of Hubei Province in China, emerged as a significant battleground in the Far East during the Anti-Fascist War. It not only gathered diverse anti-Japanese forces from across China but also attracted a large number of leftist internationalist fighters. Figures like Joris Ivens, Robert Capa, and Norman Bethune joined the International Brigades, relocating from Madrid to Wuhan. Additionally, champions of internationalism such as Edgar Snow, David & Isabel Crook, Anna Louise Strong, and Agnes Smedley arrived in China, fervently supporting the nation’s anti-fascist cause. Meanwhile, significant and profound changes occurred in the European art world. Amidst the ideological struggles between revolution and freedom, artistic revolution and revolutionary art, and even between Trotskyists and Stalinists, the Surrealist group experienced a split in 1938, and the international avant-garde cultural and artistic movement driven by left-wing ideologies gradually came to an end. The war-torn Wuhan stood as the ultimate culmination of internationalism after Madrid. These pivotal events, comprising a dialectical historical tableau, marked the epilogue of this proposal and heralded the beginning of Zheng Shengtian’s life narrative. Thus, we entitled this chapter “1938: The Last Internationalism.”

III

This proposal has received wholehearted support from Mr. Zheng Shengtian, who generously shared all his materials and attended the proposal workshops twice. He also participated in the research and brainstorming of the project multiple times, providing valuable insights into the specific content and structure of this proposal. Even in his eighties, Mr. Zheng has remained remarkably enthusiastic about his work and initiatives. The ongoing updates to “Sheng Project” inspire and encourage our younger generations.

Over the past six years, this project has also received care and support from numerous friends. Three proposal workshops were conducted, where friends from diverse fields, such as art, literature, history, politics, and ideology, both domestically and internationally, were invited to share resources and delve into topics together. These discussions sparked myriad brilliant insights, offering invaluable enlightenment. From the outset, these dialogues aided in clarifying the original aspiration of the project: avoiding a personal retrospective, avoiding attempt to restore historical scenes by studying archives, and avoiding conduct comparative studies between individual life history and social development history, as well as averting deification, projection, and historical determinism. It can be said that “A Proposal for Sheng Project” is presented in its current structure as the result of the collective wisdom of all participants at all stages, for which we are deeply grateful. Therefore, we have selected the highlights of the three workshops and included them in the proposal.

“I Was Supposed to Go to Mexico: A Proposal for Sheng Project” aims to bridge the three fragmented thirty-year periods in 20th-century Chinese history. Based on the rich assets of Zheng Shengtian’s life history spanning over 80 years, it portrays a river of life that traverses multiple art worlds, unfolds a bustling century square, and sketches an intricate maze of destiny. The depiction of the river, square, and maze not only explores the untold possibilities and potential in Chinese art history but also takes a deep dive into the encounters, struggles, attachments, and creative endeavors spanning several generations of personal life histories.

We look forward to inviting more friends to get involved through this proposal, to perceive, feel, and engage with an inclusive historical narrative from personal life experiences. By collaborating across generations, we aspire to foster a deeper understanding and emotional re-connection among different age groups, allowing forgotten and fragmented memories and narratives to resonate again with contemporary life. We believe that only in the resonance of body and mind, and amidst the sparks generated from the collision between self and events, can the past be enlightened; only by recreating a scene can we confront history—only by becoming a part of its vast can one master the past.

Translated by Ma Yanxin