2015

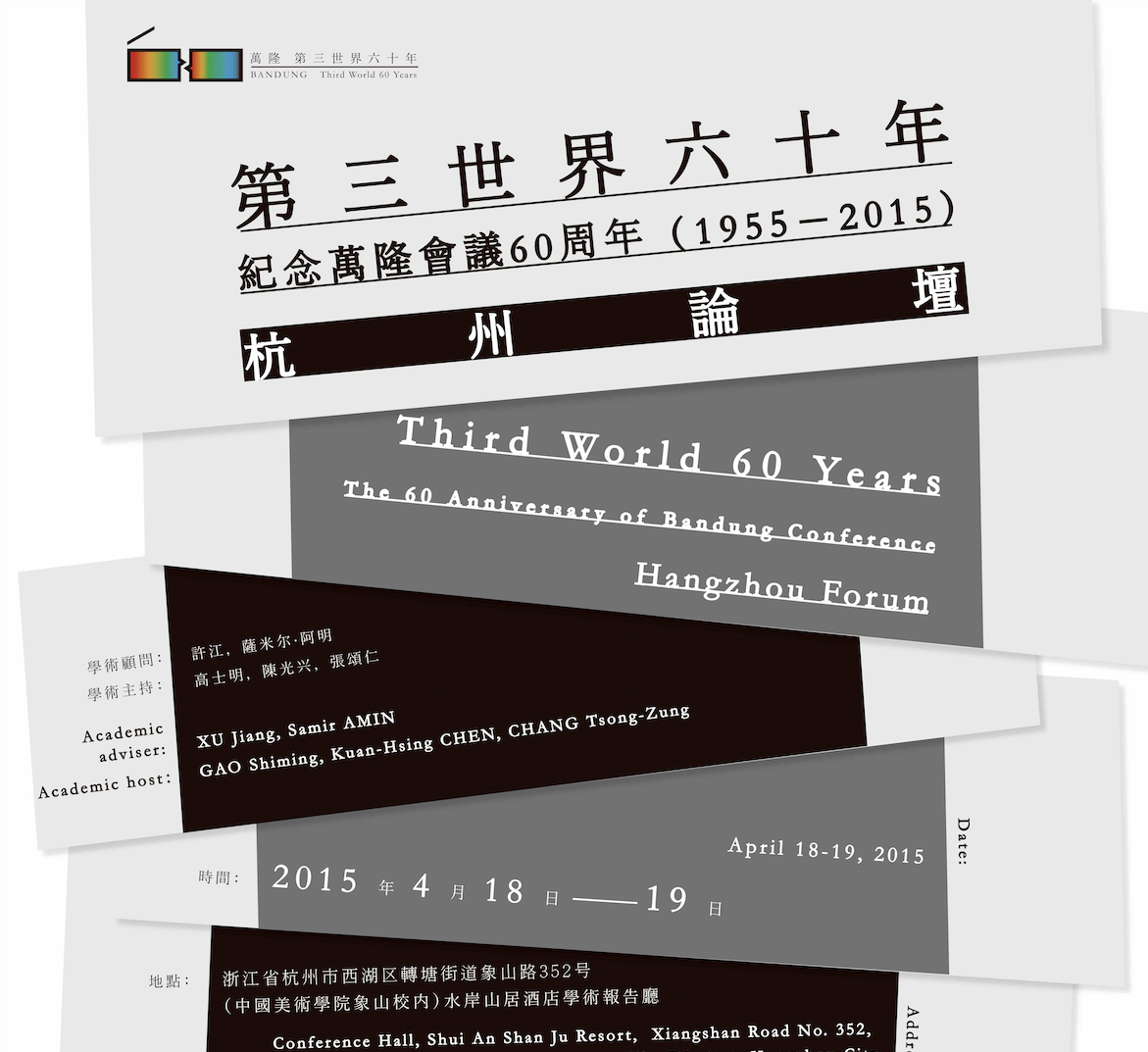

Speech at the 'Third World, 60 Years: The 60th Anniversary of Bandung Conference' Hangzhou Forum, on April 18–19, 2015. I would like to express my gratitude to the participants of this forum for their valuable suggestions on this article, including Shunya Yoshimi from the University of Tokyo, Stephen C. K. Chan from Hong Kong, Wang Xiaoming from Shanghai, Suren Pillay from the University of the Western Cape in South Africa, and Robert Meister from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

On 9 March 2015, Chumani Maxwele, a fourth-year political science student, emptied a container of feces over the statue of Cecil Rhodes at the University of Cape Town (UCT) campus in South Africa. Maxwele said he was protesting the “colonial dominance” still palpable at UCT. His actions marked the beginning of a series of events, including the occupation of UCT's Bremner Building by a group of students. A month later, the University Council voted to remove the statue. Chumani Maxwele told the media: “It has never been just about the statue. It is about transformation.” The petition circulated by the Rhodes Must Fall Campaign stated: “We demand that the statue of Cecil John Rhodes be removed from the campus of the University of Cape Town, as the first step towards the decolonisation of the university as a whole.”1

“Transformation” has surfaced as a rallying cry in the post-apartheid South African academy every time popular disaffection has found organized expression. North of the Limpopo, in the period that followed independence, there was another name for “transformation”; this was “decolonization”—political, economic, cultural and, indeed, epistemological. I intend to focus on the latter, knowledge production, and its institutional locus, the university.

The African university

The modern university has developed in a tension between two poles, on the one hand, a universalism based on a singular notion of the human and, on the other, nationalist responses to it. The challenge for us—which I do not take on in this essay but only refer to in the conclusion—is to rethink the relationship between the national state and the university. To do so is to arrive at our own understanding of the modern and the possibility of a time after colonialism.

What does it mean to decolonize a university, an authorized center of knowledge production? In one form or another, this question has been at the heart of discussions at African universities. I will focus on some of the discussion at some of the universities: the University of Dar es Salaam, Makerere University in Kampala, the University of Cape Town, and the Dakar-based Pan-African organization called the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA).

These discussions have developed as a series of debates on a range of issues: Africanization of staff, disciplinarity and inter-disciplinarity, the role of the intellectual and the relationship of the intellectual to society. The demand for Africanization was formulated in the older colonial-era universities soon after independence, in a debate that pits two principal ideas, justice and rights, against one another. The discussion on the disciplines and inter-disciplinarity developed in two very different contexts: as a discussion at the University of Dar es Salaam on the relevance of discipline-based education, and, at the University of Cape Town, as a set of questions about two different ways of understanding the human experience, with the disciplines studying the white experience and area studies focused on the experience of the native from the point of view of a settler observer. Connected to this were different understandings of the role of the intellectual and the relation of the intellectual to society. They raise further questions, about the relation of the particular to the universal, and the local to the global. Driving these discussions is a tension between two related but different vocations: that of the public intellectual and the scholar. The public intellectual emerged as organic to the anti-colonial movement, both integral to the nationalist movement and a beneficiary of the nationalist struggle. The scholar was the first critic of nationalism in power, drawing inspiration from a set of universal values guiding the study of an undifferentiated human. It would appear ironic that the scholar beholden to the governmental and university bureaucracy for his meteoric rise—in this case, Ali Mazrui—would appear critical of the newly independent government. To understand the changing relationship between the scholar and power, we shall examine the changing relation between the anti-colonial intellectual and nationalism, first as a popular movement and then as a form of power.

The African university and the legacy of the colonial modern

Most writings on the African university begin by acknowledging a list of premodern institutions as precursors to the modern African university. The UNESCO website references these venerable institutions from the precolonial and premodern periods. Big names abound: the Alexandra Museum and Library, Al-Azhar in Cairo, al-Zaitounia in Tunis, al-Karaouine in Fez, Sankore in Timbuktu, and so on. An ongoing debate focuses on whether or not these can be termed universities.

I begin by problematizing both the concept and the institutional history of the university, in its European and African contexts. My point is to underline the specifically modern character of the university as we know it and its genesis in post-Renaissance Europe. The European university emerged from Western Christianity, in the 12th and 13th centuries, and was institutionalized in Berlin in the 19th century, as the home of the study of this undifferentiated human.

The Latin word universitas means “corporation.” The word derives from the context in which the institution developed. The premodern university was a “corporation” of students and teachers whose position was defined by a privilege and an exemption. The Church sanctioned the “corporation” to teach, and the state gave it exemptions from financial and military services. In North and West Africa, as in the rest of the non-Western world, there was no counterpart to the Catholic Church. When those in power conferred the privilege of teaching or gifts on important scholars, the beneficiaries were individuals or families, not a corporation of teachers or students. To say this is to state the obvious: the overall context in the development of institutional learning (what we now know as the “university”) was not the same in these parts of Africa as in medieval Europe. This difference should raise a larger question: to what extent can we translate a modern category such as “university” across time?

The important point is that neither the institutional form nor the curricular content of the modern African university derived from pre-colonial institutions; their inspiration was the colonial modern. The model was a discipline-based, gated, community with a distinction between clearly defined groups (administrators, academics, and fee-paying students). Its birthplace was the University of Berlin, designed in 1810 in the aftermath of German defeat by France. Over the next century, it spread to much of Europe and from there to the rest of the world. Not only the institutional form of the university but also the intellectual traditions that have shaped modern social and human sciences are a product of the Enlightenment experience in Europe. The European experience provided the raw material from which was forged the category “human.” Although abstract, this category drew meaning from actual struggles on the ground, both within and outside Europe.

The experience from which the category human was forged was double-sided and contradictory. Internally, the notion of the human was a Renaissance response to Church orthodoxy. The human developed as an alternative to the notion of a Christian. Looking to anchor their vision in a history older than that of Christianity, the revolutionaries of France and Europe self-consciously crafted a European legacy, with its origin in classical Greece and imperial Rome. This human was more than Christian; theoretically, at least, it included those other than Christian. Externally, the notion of the human was a response to an entirely different set of circumstances—marked, not by the changing vision of a self-reflexive and revolutionizing Europe, but of a Europe reaching out and expanding in a move seeking to conquer the world—starting with the New World, then Asia and finally Africa—and then to “civilize” that world in its own image.2 Imperial Europe understood the human as a European, but colonized peoples as so many species of the sub-human.

This dual origin made for a contradictory legacy. In their universal reach, both the humanities and the social sciences proclaim the oneness of humanity and define that oneness from the vantage point of a very particular experience and its equally particular and imperious perspective. Rather than acknowledge the plurality of experience and perspective, the universalism born of the European enlightenment sought to craft a world civilization as an expression of sameness. It is the linear theory of history undergirded by this particularity of vision, and the power that drives it, that we have come to know as Eurocentrism (Amin 2010). It is this vision, and this institutional form, that was transposed to the colonies. Decolonization would have to engage with this vision of the undifferentiated human—culled from the European historical experience—which breathed curricular content into the institutional form we know as the modern university.

We can only speak of the advent of the modern university in Africa in the colonial period. Colonial universities were set up in two different phases. The first phase saw the establishment of universities at two ends of the continent. At the southern end, as with the University of Witwatersrand and the University of Cape Town, universities were an external implant. In the northern part, existing institutions such as Al-Azhar were “modernized” into discipline-based, gated communities in the image of the modern Western university (Gubara 2013).

When it came to sub-Saharan Africa, the middle bulge of the continent south of the Sahara and north of the Limpopo, the part of Africa colonized last in the late 19th century, modern universities were set up only in the 20th century. The difference between these two parts of Africa captured a difference between two historical periods: the 18th and early 19th century, when colonialism had the self-image of a “civilizing mission,” and the following century, which marked a retreat from this confident mission to a preoccupation with defending order as “customary.” Whereas universities were seen as the hallmark of the “civilizing mission” in the earlier period, they were seen as harbingers of an unruly middle class intelligentsia in the period that followed.3 This policy imperative was formulated by Sir Frederick Lugard, the scholar-administrator of British Africa. He warned of the educated native—the “Indian Disease”—and said this disease must be kept out of Africa as far as possible (Lugard 1965).

For both its institutional character and its curricular content, the colonial university drew on the modern European university, not the precolonial and the premodern tradition in Africa. The particular experience of the colonial modern shaped the internal dynamics and external perspective of the university. At the same time, universities in middle Africa were mainly a post-independence creation. They were a product of insurgent nationalism. There was one university in Nigeria at independence in 1961, 31 universities three decades later (Bako 1993). The figures for East Africa, where Makerere was the only university in the colonial period, are not that different. As the midwife of the modern university, the modern state had a limited vision: the university would produce the personnel necessary to deracialize the state and society. Limited to deracialization of personnel, both within the university and in the wider society, this vision had yet to engage either the institutional form or the curricular content that breathed life into it.

It is against this background that we can understand subsequent initiatives to reform this university.

Intellectuals, state and society in the post-independence era

Post-independence reform unfolded in two waves. The first wave was about access—Africanization—and the second about institutional reform. Given that racial exclusion was a standard feature in every colony, Africanization was a common demand throughout colonial universities in the aftermath of independence. The demand for access generated a debate between two general positions: rights and justice. The beneficiaries of racial discrimination called for equal rights for all on the morrow of independence. Its victims demanded that if discrimination was racialized, then justice too should be racialized. Whether at Makerere University in the early 1960s or at South African universities during the apartheid era, the defense of rights turned into a language for minimal reform while defending historical privilege, calling for a focus on the present and forgetting the past (moving on, let bygones be bygones). In contrast, justice provided a language for those who aimed at a thoroughgoing reform of this status quo, calling for affirmative action to redress the effects of the past. Both languages, rights and justice, were racialized in the post-colonial context. At one end of the political spectrum, the failure to think of rights outside the context of justice led to an embrace of the social inequality generated by apartheid; at its other end, the failure to think of justice outside the context of rights produced an agenda for turning the tables, in other words, revenge.

At the same time, the struggle for access had two very different histories, depending on context. Where there was no appreciable locally-settled European population and hardly any European students in local universities, as in the non-settler colonies, access was about inclusion in the teaching faculty and the top administration, and was relatively easy to achieve—and could be done without a change in the curriculum. But in settler colonies, where universities were divided into two neatly differentiated institutional categories, “white” and “black,” the integration of white universities was likely to be explosive. This is for several reasons. To begin with, the institutional separation of “white” and “black” educational institutions, whether university or pre-university, was part of a wider world of unequal access to resources, and thus unequal quality of education. This meant that when historically white universities responded to demands for social justice by admitting more “black” students through affirmative admission policies, the same universities failed—and expelled—a disproportionate number of black students as they sought to defend standards. For the black student in a historically white university, this made for an acutely alienating experience, leading the more perceptive of these students to call for a change in the content of the curriculum, one that would valorize the black (“native”) experience, and not just relegate it to the domain of area studies. This difference had further consequences: whereas the demand for access could be screened off from the demand to transform the university in non-settler contexts, this would not be so easy in settler contexts, as evidenced by the round of struggles initiated by the Rhodes Must Fall movement at the University of Cape Town. Although the demand for changing the curriculum came in non-settler contexts first—after all, political independence came to non-settler colonies in a wave of reform starting in the mid-1950s—it did not have a racial edge, as in settler contexts.

The reform movement of the 1960s unfolded in non-settler colonies. Located at two very different campuses—Makerere University, the paradigmatic colonial university, and the University of Dar es Salaam, which would soon emerge as the flag-bearer of anti-colonial nationalism—this movement was guided by two individuals championing two contrasting visions. Ali Mazrui called for a university true to its classical vision, as the home of the scholar “fascinated by ideas”; Walter Rodney saw the university as the home of the public intellectual, a committed intellectual rooted in his time and place, and deeply engaged with the wider society. From these contrasting visions would emerge two equally one-sided notions of higher education: one accenting excellence, the other relevance.

Makerere was a public university, first established in 1922 by the colonial government as a vocational college. Key administrators, appointed by the newly independent government, dictated both the direction and pace of change. The first round of change produced resounding victories for the broad nationalist camp, which called for an “Africanization” of academic and top administrative staff so the university would be national not only in name but also in composition. This change was easy to effect. With it, however, the terms of the debate changed. As the ruling party moved to consolidate its hold on power as a single party regime, the university once again turned into an oasis where the practice of academic freedom also guaranteed free political speech for those who disagreed with the ruling power. This in turn made for a growing tension between the nationalist power and the intelligentsia at the national university. A product of insurgent nationalism, the university came into collision with nationalism in power, as in most African countries.

“Africanization” made for a meteoric rise in the career of young scholars. The best known of these was Ali Mazrui. Freshly returned from Oxford with a DPhil, Ali was promoted to become Makerere's youngest professor and the head of its Department of Political Science and Public Administration. The turning point at Makerere was the birth of the magazine Transition (1961–1968). Edited by Rajat Neogy, and joined by an array of scholars and public intellectuals, Transition was a blend of two different kinds of media, a journal and a magazine, and provided space for university-based intellectuals to write for a public that included both the gown and the town. Designed to be a literary organ for East Africa's writers and intellectuals, Transition became what many considered Africa's leading intellectual magazine. Those who wrote for Transition ranged from leading novelists (Nadine Gordimer, Chinua Achebe, James Baldwin, Paul Theroux) to state leaders (Julius Nyerere).4

The output of Transition included several essays that lived beyond their times. Mazrui's writings chided left intellectuals caught in the drift to single party rule in countries where the regime took a “left” stance, for timidity and soft hands. Two of his essays in particular come to mind. “Tanzaphilia” was about the relation between left-wing academics and Julius Nyerere in Tanzania; Mazrui argued that the “committed” intellectuals at the Hill in Dar es Salaam had lost their critical eye and become intoxicated with Julius Nyerere. Another essay, “Nkrumah: the Leninist Czar,” poked fun at another left icon. Paul Theroux wrote, “Tarzan is an expatriate” and “Hating the Asians.” The first was a political reading of literary characters, Tarzan and Jane, as prototype expatriates, minimally clad, committed to enjoying pleasures of the flesh and holding leftist options in a lovely climate—but with minimal consequences. The second focused on how the anti-colonial struggle had ended with a convenient compromise between the colonizer and the colonized: those at the top (whites) and bottom (blacks) ends of East Africa's colonially-produced racial hierarchy periodically came together to target the minority Asian community as a convenient scapegoat. The same group that produced Transition also produced public debates in the city—around the clock tower—between government intellectuals and Makerere dons, in particular the Attorney General Adoko Nekyon and the professor Ali Mazrui, on issues of public interest.

This is the context in which a series of memorable debates were held, first at Makerere and then at Dar es Salaam, between Walter Rodney of the University of Dar es Salaam and Ali Mazrui of Makerere. These debates brought into conversation and confrontation two different standpoints in the ongoing public debate. Rodney called on intellectuals to join the struggle to consolidate national independence in an era where imperialism reigned supreme even though colonialism had ended. In contrast to Rodney's preoccupation with the external, Mazrui called for a focus on the internal, on the struggle for democracy in an era when a new form of power was consolidating. If Rodney focused on the outside of nationalism, Mazrui called attention to its inside. If Rodney called on intellectuals to rally around the need to consolidate national independence, and thereby realize the unfinished agenda of anti-colonialism, Mazrui called attention to the authoritarian tendencies of nationalism in power. The debate between the two mirrored larger societal processes, the tension between nationalism and democracy, and a sharpening contest between state and society. In this sense, Mazrui was the first critic of nationalism from the standpoint of democracy.

The disciplines and inter-disciplinarity

The debate around disciplinarity unfolded in two different contexts: the University of Dar es Salaam in the 1970s and the University of Cape Town in the 1990s. It is worth keeping in mind the difference between these debates. Whereas the demand for inter-disciplinarity was advanced as the cutting edge of reform at the University of Dar es Salaam, it was seen as part of a problematic legacy at UCT.

The Dar discussion unfolded in the context of rapid political change, triggered by a student demonstration on 22 October 1966, protesting a government decision to introduce compulsory national service for all secondary school graduates. Claiming that the original decision was necessary “to prepare educated youth for service to the nation,” the government sent all 334 students home and canceled their bursaries. In another few months, on 5 February 1967, the president, Julius Nyerere, issued a statement—the Arusha Declaration—announcing a radical change in official policy. There followed a program of nationalization—socialism. The university's response was to organize a conference on the Role of the University College, Dar es Salaam in a Socialist Tanzania, from 11 to 13 March 1967. The conference ended with a call for relevance, noting that “various disciplines and related subjects [were not studied] in the context of East Africa's and particularly Tanzania's socio-economic development aspirations, concerns and problems.” Among the recommendations was one for a “continuous ‘curriculum review’” (Kimambo 2008a, 147).

The conference triggered vigorous debates among both the academic staff and students on campus. Accounts of these discussions identify three different points of view. Radicals wanted a complete transformation, of both curriculum and administrative structure; above all, they wanted to abolish discipline-based departments. Moderates, who were the majority and included most Tanzanian members of staff, agreed that there should be a radical review of the curriculum but not an abolition of departments. Conservatives resisted any radical change in either curriculum or the discipline-based organization of the university.

There followed two rounds of reform. The first round began with the introduction of an inter-disciplinary program in “development studies.” But changes were ad hoc and contradictory: inter-disciplinary “career streams” were introduced but within the departments that remained. The response was mixed, and opposition was pronounced. A professor in the Law Faculty (Kanywanyi, 1989) recalled “political-rally like classes” where “speakers were drawn mainly from outside the college” including “Government Ministers and other public figures of various calling.” The course “became unpopular among students”—indeed, students rejected the new curriculum in 1969.5 Perhaps the most acute observation came from a sub-committee of the University Council, appointed in November, 1970 to review the program.6 It began by noting that the compromise that had introduced streams but retained departments was contradictory: “Some departments have departed drastically from the sub-stream structure in their attempt to respond to the market situation.” The resulting tension “proved right the fears of those who were opposing co-existence of streams and departments which has enabled disciplines to reassert themselves at the expense of the inter-disciplinary programme.” More importantly, the sub-committee asked whether a problem-solving focus was likely to reduce the scholarly content of higher education, producing “technocrats” rather than “reasoning graduates” (Kimambo 2003, 5, 7). The academic staff opposed to the changes either voted with their feet or were booted out of the university. Between June and November, 1971, 28 academic staff resigned and 46 academic contracts were not renewed. Of 86 academics in established posts, 42% departed. In light of this, the Council sub-committee called for “careful preparation” and recruitment of new staff.

Round 2 began with a two-track institutional reorganization. The Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences set up its own inter-disciplinary core to be taught by its own faculty. The Institute of Development Studies (IDS) was set up to teach an inter-disciplinary core in all other faculties, including the sciences and the professions. IDS hired over 30 academic staff between 1973 and 1990. Departments remained, but so did career streams and sub-streams. The curriculum was revised and a compulsory inter-disciplinary curriculum was introduced at all levels. The inter-disciplinary core in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, known as EASE (East African Society and Environment), focused on the teaching of history, ecology and politics in the first year, taking 40% of student class time (two of five courses). In the second and third years, the time devoted to the inter-disciplinary core course was reduced to one course out of five, focusing on the history of science and technology in year 2 and development planning in year 3.

The decolonization of curricular content developed as the result of two parallel but connected initiatives. Besides formal changes in curriculum, especially the introduction of compulsory inter-disciplinary courses, there were more informal initiatives, undertaken by the radical reform-minded staff, which brought together academic staff and students under common umbrellas. Two in particular deserve mention. The first was known as the “ideological class” and was deliberately organized at 10 a.m. every Sunday. Its stated aim was secular, to provide students with an alternative to Church attendance. The second comprised a range of after-class study groups that proliferated over the years. I recall, in 1975, I belonged to six study groups, of between two and eight members, each meeting once a week, each requiring a background reading of around 100 pages. The thematic focus of each group was as follows.

1. Das Capital;

2. The Three Internationals;

3. The Russian Revolution;

4. The Chinese Revolution;

5. The Agrarian Question;

6. Ugandan Society and Politics—The Changombe Group.

Except for the last group which was formed by Ugandan exiles, from both within and outside the university, no group focused on Tanzania, East Africa, or Africa. Reflecting on this experience from today's vantage point, I am struck by two absences. One, the study of the international left tradition did not include a study of the left tradition regionally, nationally, or locally. Second, all readings and all groups were in English; there was no attempt to read any texts in Kiswahili.

This was a period of tremendous intellectual ferment, marked by two different trajectories, each set in motion by a different work. The first, written in the mode of dependency theory, was Walter Rodney's How Europe Underdeveloped Africa and was very much in line with the Arusha Declaration. The second contrasted the language and promise of the Arusha Declaration with the reality of social and political developments that followed. Two books authored by Issa Shivji, The Silent Class Struggle, and Class Struggles in Tanzania, reflected the accent on internal processes. The publication of Shivji's books triggered a debate among academics at Dar, focused on imperialism and the state.7 If Ali Mazrui was the first major liberal intellectual critic of nationalism in power, Issa Shivji was its major intellectual critic from the left.

The curriculum reform movement at the University of Dar es Salaam needs to be understood in its broader political context, marked by the Arusha Declaration. At the same time, the movement was not the result of reforms introduced from above; it was both shaped and sustained by an intellectual social movement from below. This social movement included a wide range of social actors, from university academics to student activists, from formally constituted bodies such as the youth wing of the ruling party, to student magazines such as Maji Maji and Che Che.

The difference in context with the debate on the disciplines that unfolded at the University of Cape Town two decades later is worth noting. The UCT debate arose as part of initiatives to reform the curriculum following the end of apartheid. The University created a Chair in African Studies (the AC Jordan Professor of African Studies) and proposed the introduction of a first year inter-disciplinary course on Africa to be taught by the holder of the Chair.8 The course was to be compulsory for all students entering the university. The ensuing debate focused on the content of the course: Should South Africa be a part of the curriculum in a course on Africa? What should be the relationship between the disciplines and the inter-disciplinarity characteristic of area studies?

The question of whether or not the teaching of South Africa should be part of a curriculum on Africa targeted a widely-held assumption in the South African academy, that the South African experience was exceptional. The conventional practice in the South African academy was to separate the teaching of the “native” experience from that of the “settler” when it came to the study of South Africa. This is how the question was formulated at the outset of the discussion at the Centre for African Studies at UCT in November, 1996:

To create a truly African studies, one would first have to take on the notion of South African exceptionalism and the widely shared prejudice that while South Africa is a part of Africa geographically, it is not quite culturally and politically, and certainly not economically. It is a point of view that I have found to be a hallmark of much of the South African intelligentsia, shared across divides: white or black, left or right, male or female. (Mamdani 1996b, 3–4).

I still hold to these observations, but observe in hindsight that their impact at the time was no more than that of a ripple in a pool, mainly because the analysis came from a scholar who had parachuted from the outside, and had little contact with either the scholarly community—students included—at UCT or with social movements outside its gates.

The debate around the compulsory introductory course brought into sharp focus both the question of South African exceptionalism and that of the division between the disciplines and inter-disciplinary area studies.

The key question before us is: how to teach Africa in a post-apartheid academy. ... Historically, African Studies developed outside Africa, not within it. It was a study of Africa, but not by Africans. The context of this development was colonialism, the Cold War and apartheid. This period shaped the organization of social science studies in the Western academy. The key division was between the disciplines and area studies. The disciplines studied the White experience as a universal, human, experience; area studies studied the experience of people[s] of color as an ethnic experience. African Studies focused mainly on Bantu administration, customary law, Bantu languages and anthropology. This orientation was as true of African Studies at the University of Cape Town as it was of other area study centers. (Mamdani 1998)9

Centers for the study of Africa as an “area” originated in the Western academy and were imported to universities in settler colonies. The universities in non-settler colonies, both those few like Makerere established under colonialism, and the many established under nationalist power, saw themselves as continuing in the tradition of the Western academy, centers for the study of the human, although in an African context. But this focus on context never meant that the African university limited itself to the study of Africa; it was unequivocally a center for global study.

In practice, however, most African universities—Makerere as much as UCT—developed as regional universities where the focus was the region and the West, with developments in the rest of the world accessed through media and extra-curricular reading. The exception was the University of Dar es Salaam. Dar was a Bandung university, where the focus of intellectual discourse had moved to “decolonization” and “revolution” across the formerly colonized world.

The intellectual and society: the scholar and the public intellectual

The South African debate unfolded inside UDUSA, the Union of Democratic University Staff Associations. The debate focused on how to respond to two defining inequalities generated by apartheid in the university system in South Africa, the first between historically white and historically black universities, and the second between white and black students in tertiary institutions. Once again, the two sides to the debate rallied behind familiar banners, defense of excellence and the pursuit of relevance.

In a paper on “Tertiary education in a democratic South Africa” (1991, cited in Wolpe and Barends 1993), the South African labor historian Van Onselen traced inequalities in the educational system to different experiences: whereas white universities had “developed legitimately” and “organically” in relation to the core life of the economy, black universities at the periphery were the result of an “artificial” development, through social engineering. Stuart Saunders, a former Vice Chancellor of UCT, elaborated this point of view: “Nurtured by their links to the core political economy, the white universities developed into centres of excellence indexed by high reputation ratings, access to resources, good student outputs and the development of talent or ‘value added’ reflected in research and publications” (Saunders 1992). By contrast, the historically black universities remained as they began, “peripheral institutions with poor ratings on all these indices.”10 No doubt the relationship to the “core political economy” played a role, but surprisingly absent was any reference to the relationship to the core political power.

My first encounter with this debate was in July 1992, when I was invited to the annual convention of UDUSA, Union of Democratic University Staff Associations, in Durban. As the discussion unfolded, I understood that excellence and relevance had become code words in the ongoing debate: critics saw the call for the pursuit of excellence as a veiled defense of apartheid-era privilege; they looked to relevance (and access) to challenge exclusivity. But there was more to the difference between white and black universities than just a defense of privilege.

The discourse of white universities was two-sided. On the one hand, they explained away privilege as the result of merit—calling on one and all to defend their privileged access to resources as a defense of academic standards, necessary for the advancement of scholarly excellence. On the other hand, they waged an ongoing and successful struggle for administrative and intellectual autonomy—academic freedom—as necessary for the pursuit of academic excellence.

The experience of black universities sharply contrasted with this tradition: black universities had been run as so many extensions of the administrative apparatus of the apartheid state. In the absence of administrative autonomy, any struggle of significance in black universities took on an immediately political significance, and brought the academic community face-to-face with the apartheid bureaucracy in a direct encounter. Intellectuals in black universities called for academic freedom for all, whether in white or black universities. Anything less would mask a defense of privilege of intellectuals bred in greenhouses. When white intellectuals joined the anti-apartheid movement (and many did), the tendency was to develop these commitments outside the university. In this contest, the two sides developed contrasting visions of self: white “scholars” and black “public intellectuals.”

CODESRIA and the public intellectual

Begun with donor encouragement and funding in 1973, as a council of directors of institutes of economic and social research in Africa, CODESRIA transformed itself over the years into a Council for the Development of Social (and Economic—in the original formulation) Research in Africa. In spite of its name, CODESRIA became a home mainly for two groups of researchers. The first came from small countries, countries with a one government—one national university syndrome. Because their context made for an eyeball-to-eyeball confrontation between governments and scholars, these scholars found cross-border freedom in CODESRIA. The second group comprised exiled scholars from countries undergoing rapid social and political transformation, such as Ethiopia and Egypt. The least represented were scholars from countries that had the largest number of universities, large enough to have national professional associations and academic journals. This group included Nigeria and South Africa.

Organized more as a series of symposia and conferences with small panels and large audiences, CODESRIA lent itself to public debates around issues of public interest. It was a ready-made forum for public intellectuals. At the same time, a variety of other forums—multi-national research groups, the national working groups, and small grants program for doctoral research—provided space to nurture young scholars.

No great books were written under the umbrella and sponsorship of CODESRIA. At the same time, scholars who wrote important works (Samir Amin, Archie Mafeje, Claude Ake, Thandika Mkandawire, Ifi Amadiume, Issa Shivji, Wamba-dia-Wamba, Sam Moyo) turned to CODESRIA to initiate debates that would change public discourse on the continent: such, for example, was the case with debates on dependency, democracy, gender, and then the land question.

The tradition of public debate came under sharp criticism in the late 1990s with the appointment of Achille Mbembe, fresh from a teaching position in a US Ivy League university, as Executive Secretary. Determined to draw a sharp line between public debate and scholarly discussions, and thereby redefine CODESRIA as a scholarly enterprise and remove it from the arena of public debate, the new Executive Secretary decided to open institutional doors to fresh thinking. The hallmark initiative marking this new beginning was a social science conference in Jo'burg in 1998. A host of Western scholars with an international standing were invited to present papers—and African scholars were asked to respond as local discussants. If the object was to shake up the gatekeepers of the African post-colonial academy, it was more than successful. But more than just shaking up these members of the first generation post-independence intellectual elite, it outraged them with the specter of a return to an arrogant colonial-type racial pecking order—in which the Western intellectual was the “scholar” and his/her African counterpart a native “apprentice.” At the same time, if the point was to inaugurate a process shaping a new and more scholarly research agenda, it did not get off the ground.

As the debate heated up, the two sides gave—or called—each other names: “globalists” and “Pan-Africanists.” “Globalists” criticized CODESRIA's preference for the large symposium and for conferences that they said had politicized intellectual work and tailored scholarship to meet the demands of public debate and discussion. “Pan-Africanists” called for a defense of CODESRIA as an all-African institution, a protected space for forging an African research and intellectual agenda. Triggered by the brazen intervention of the new Executive Secretary, the debate between “globalists” and “Pan-Africanists” did not survive his departure. But it also pre-empted a more important intellectual discussion that has yet to take place.

CODESRIA developed as a non-disciplinary space where we all shed our disciplinary specializations and took on a non-disciplinary perspective; on the downside, all took on the mantle of political economy. The more political economy emerged as the master discipline in the academy, the more it came to be marked by different tendencies; whether on the left or the right, each heralded the human as an “economic man.” In the US, the disaffection with hegemonic aspirations of political economy gave way to literary studies, with the focus on material giving way to the study of representation. This context helps us understand the unintended consequence, the intellectual downside, of the “expulsion” of Mbembe from CODESRIA. The hegemony of political economy was inscribed in the newest and most innovative departure in the post-colonial academy: the core of the inter-disciplinary program called EASE and Development Studies at the University of Dar es Salaam was political economy; even the Dar es Salaam School of History was known for a perspective anchored in political economy; and, above all, CODESRIA was the home of radical scholars who swore by political economy, as if it were an oath of loyalty. It was, after all, Mbembe who had attempted to steer CODESRIA away from political economy and towards a focus on discourse and representation. Whereas this top-down effort alienated one and all, it also delayed a debate around political economy and the epistemological question in CODESRIA.

Decolonization, the public intellectual and the scholar

Our understanding of decolonization has changed over time: from political, to economic to discursive (epistemological). The political understanding of decolonization has moved from one limited to political independence, independence from external domination, to a broader transformation of institutions, especially those critical to the reproduction of racial and ethnic subjectivities legally enforced under colonialism. The economic understanding has also broadened from one of local ownership over local resources to the transformation of both internal and external institutions that sustain unequal colonial-type economic relations. The epistemological dimension of decolonization has focused on the categories with which we make, unmake and remake, and thereby apprehend, the world. It is intimately tied to our notions of what is human, what is particular and what is universal. This debate has not found room in CODESRIA. For now, at least, it is confined to individual campuses and programs, such as the PhD program in Social Studies at Makerere Institute of Social Research.

The challenge of epistemological decolonization is not the same as that of political and economic decolonization. If decolonization in the political and economic realms not only lends itself to broad public mobilization but also calls for it, it is otherwise with epistemological decolonization, which is removed from the world of practice and daily routine by more than just one step. Yet it is not detached from this world. This is why epistemological labor radically challenges the boundary between the public intellectual and the scholar, calling on each to take on the standpoint of the other.

The public intellectual and the scholar are not two different persona. They are two distinct perspectives, even preoccupations, one drawing inspiration from the world of scholarship, the other from that of public debate. But the distinction between them is not hard and fast; the boundary shifts over time, and is blurred at any one point in time. The tensions were evident in the early post-independence period. For a start, if the public intellectual hoped to work closer to the ground, to be as close to the ground as possible so as to work with local communities, the scholar had “universalist” aspirations that flowed from the claim that he or she was a universal intellectual who traded a global ware, theory. The split between the two was also often pregnant with political significance: the public intellectual took sides as a partisan, whereas the scholar claimed objectivity as an observer, a Hegelian witness—“the owl of Minerva”—whose wisdom came in the wake of events to which he and she must relate as witnesses rather than partisans.

Today, however, the ground is shifting under both identities as the international donor institutions seek to reshape the African academy. In this new context, it is not the university but the think tank, whether within or outside the university, that is emerging as the new home for the public intellectual in the neo-liberal era. The mission is to depoliticize the public intellectual, and at the same time anchor both the public intellectual and the scholar to an official agenda. Unlike in the 1960s and 1970s, the public intellectual of the early 21st century cannot be presumed to be a progressive intellectual; in this era, the “public” is no longer just the “people,” it also includes the government, and the donor and the financial institutions on which governments increasingly depend. The new type of public intellectual is recruited and funded by these organizations to do constant monitoring of public institutions, both from within and from the outside, in the name of “accountability.” The same process—a combination of “accountability” and “transparency”—aims, in turn, constantly to monitor this new type of public intellectual. In fact, the public intellectual based in a think tank is expected to serve the government above all, as the guarantor of “evidence-based policies.”

In this context of think tanks and funding from international donor and financial institutions, the new type of intellectual is called upon to think strategically and tactically, both in response to a situation s/he does not make and as an alternative to being a handmaiden of policy. To think in this way is to transpose the idea of the guerrilla into the intellectual realm, to redefine the terrain of struggle as we link basic research to public policy but at the same time redefine the approach to public policy making, so as to challenge the notion that public policy must be formulated “from above,” and thereby to democratize the formulation of public policy, whether “from below” or “from above.” Rather than participate in formulating official policy as its handmaiden, as an “advisor,” this calls on the public intellectual to take on a double task: on the one hand, subject official policy to a critical appraisal and, on the other, formulate policy alternatives with the specific object of democratizing the policy making process. From this point of view, policy-making ceases to be just a matter of technical expertise; it becomes a matter of democratic choice. This change of perspective, too, is key to decolonization.

In the half-century since independence in this part of the world, the dialectic between the public intellectual and the scholar has gone through a number of significant shifts. The first big shift took place with independence. Few at the time understood the changing perspective and role of the public intellectual in a post-colonial setting. The role of the public intellectual in a colonial university was relatively unambiguous: the public intellectual found a comfortable home in the ranks of the nationalist movement. As nationalists came to power, they differentiated politically, between moderates comfortable with the existing international order, and radicals calling for its reform. But whether moderate or radical, nationalists in power had little patience with domestic critics, especially if those spoke in the vernacular and tried to link up with social movements. This introduced a tension among radical intellectuals on how to relate to yesterday's “comrades,” now in power: as allies in a broad camp, or as critics of the new power? This tension was most palpable at the University of Dar es Salaam.

The second big shift is taking place now on the heels of the development of an expanded NGO movement, most of which has already been retooled to act as so many whistle-blowers who must ensure the “accountability” and “transparency” of the government in power. If NGOs act as so many sentries for the neoliberal order, the new public intellectuals are expected to shed the politically partisan character of the old public intellectual, so as to function as so many in-house advisors to governments of the day. The object is to deploy those trained to be “scholars”—credible sources of professional and independent opinion—for a new mission, this time to quarantine the nationalist project. The effect would be to harness the new “public intellectual” not only to “assess” the effects of “politics” but also to check the impact of society on the state through a set of negative biases, whether national, racial, ethnic or communal.

Many of the debates that I review here were marked by two keywords: relevance and excellence. They raise two questions: will a one-sided quest for relevance produce, in the words of the University of Dar es Salaam Council sub-committee, “technocrats” rather than “reasoning graduates”? And will an unadulterated emphasis on scholarly excellence produce, in Mazrui's self-definition of an intellectual, a person “fascinated by ideas” but—critics charged—without social commitment, and thus at the mercy of the powers that be? Historically, relevance and excellence have functioned as code words, each signaling a different trajectory in the historical development of the university: excellence as a call for an academic pursuit in line with the universal-imperial study of the human, and relevance as the name of a mission to transform the university into a nationalist institution, both the product of the anti-colonial project and an instrument for its continued waging.

If the tension between the public intellectual and the scholar informed the public role of the intellectual as a social critic, another tension—between disciplinarity and non- (or multi- or anti-) disciplinarity—informed the role of the intellectual as producer of knowledge, and thereby of decolonized subjects who are either public intellectuals and/or scholars. In a colonial context, the tension between the scholar and the public intellectual reflected a wider divide, between one who produces theory and one who applies it. Colonialism brought not only theory from the Western academy but also the assumption that theory is produced in the West and the aim of the academy outside the West must be to apply that theory. Its implication was radical: if the making of theory was truly a creative act in the West, its application in the colonies became the reverse, a turnkey project. This was true on the left as well as on the right, whether student effort was going into the study of Marx and Foucault or Weber and Huntington. One student after another learned theory as if learning a new language—some remarkably well, others not so well. It is these others, as they stutter in translation, who give us an idea of what is wrong with the notion that to be a student is to be a technician, learning to apply a theory produced elsewhere.

Shame, as Marx once said, can be a revolutionary sentiment. We risk producing a high-cost caricature, yet another group of mimic men and women stumbling into a new era. The alternative is to rethink our aspiration, not just to import theory from outside as another turnkey developmentalist project, but to aim differently and not just higher: to theorize our own reality.

Perhaps the best example of intellectual labors that have gone into rethinking received categories of thought, to challenging a linear universalist understanding of the human and thereby formulating new categories adequate to understanding and valorizing particular histories and experiences is the work of Nigerian historians of the University of Ibadan and Ahmadu Bello University. I am thinking of the work on the oral archive for the writing of a history of the premodern, and that on the historicity of ethnic identity by historians from Dike to Abdullahi Smith and, above all, Yusufu Bala Usman.11

Is there a single way forward for all, or many ways, each evoking a different historicity, imagined and realized by a different and changing balance of social forces? That historicity, in turn, is a tangled web of two tendencies—universal and particular, imperial and local, internationalist and national—so much so that it is neither possible to return to a past, an era gone by, nor to shed it and melt into the universal. If the future is constantly remade, so is the past, and thus the articulation between the two. The making of this future, and this past, belongs to the domain of epistemology, the process of knowledge production, and remains central to the decolonization of knowledge production.

Notes

1. https://www.change.org/p/the-south-african-public-and-the-world-at-large-we-demand-that-the-statue-of-cecil-jo

hn-rhodes-be-removed-from-the-campus-of-the-university-of-cape-town-as-the-first-step-towards-the-decolonisation-of-the-university-as-a-whole. See, also, Cape Argus, Cape Town, April 10, 2015

2. For a discussion of Spanish theologians drew on Aristotle's distinction between “natural” and “social” slaves to underline the historical and moral significance of the Spanish Crown's subordination and colonization of Ameri-Indians, see Pagden (1987, 1998).

3. The reason was the encounter with anti-colonialism, whether as nationalist or as proto-Islamist. In the British case, the high point of that encounter was the Indian Uprising (1857), the Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica (1865) and the al-Mahdiyya in Sudan (1881–1898). Together, these made for the mid-19th century crisis of empire. It marked a retreat from a “civilizing mission” that sought to eradicate custom to a preoccupation with order that led to harnessing custom in the form of customary law. The intellectual rationale for this shift came from the legal anthropologist, Sir Henry Maine. For a fuller discussion, see, Mamdani (2013, 1996a).

4. Rajat Neogy was jailed by Milton Obote on sedition charges in 1968. Transition was revived in Ghana in 1971, and its editorship was taken over by Wole Soyinka in 1973. It folded in 1976 for financial reasons, and was then revived in 1991 by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., who brought it to the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African-American Research at Harvard University where it continues to be based, dislocated both in terms of its vision and its place.

5. See J.L. Kanywanyi (1989), cited in Kimambo (2008b, 107–132; see, in particular, 120).

6. Unless otherwise specified, the details in this and the next paragraph are drawn from Kimambo (2008b, 118, 124, 125).

7. See Nabudere (1976) and Tandon (1979).

8. I was the first holder of the Chair.

9. The binary racialized distinction between the inter-disciplinary study of the “native” experience and the disciplinary study of the “settler” experience began to erode as radical scholars—across races—began to be involved in working class and trade union struggles. The ensuing study of working class mobilization and organization was incorporated in the mainstream curriculum in the Departments such as Sociology and History at universities such as Wits.

10. Cited in Wolpe and Barends (1993).

11. For a brief discussion, see, Mamdani (2013, ch. 3).

Acknowledgement

A version of this paper was delivered at a forum commemorating the 60th anniversary of the Bandung Conference, held in Hangzhou, China, on 18–19 April 2015, by the Inter-Asia School. I would like to acknowledge comments by discussants of this paper at the Inter-Asia Forum: Shunya Yoshimi, Tokyo University; Stephen C.K. Chan, Hong Kong; and Wang Xiaoming, Shanghai. I also acknowledge subsequent comments by Suren Pillay of the University of Western Cape and Robert Meister of the University of California at Santa Cruz.

References

Amin, Samir. 2010. Eurocentrism. 2nd ed. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Bako, Sabo. 1993. “Education and Adjustment in Nigeria: Conditionality and Resistance.” In Academic Freedom in Africa, edited by Mahmood Mamdani and Mamadou Diouf, 150–175. Dakar: CODESRIA.

Gubara, Dahlia El-Tayeb M. 2013. “Al Azhar and the Orders of Knowledge.” PhD thesis, Columbia University.

Kanywanyi, J.L. 1989 “The Struggles to Decolonize and Demystify University Education: Dar's 25 Years' Experience Focused on the Faculty of Law, October 1961 – October 1986.” Eastern Africa Law Review 15.

Kimambo, Isaria N. 2003. “Introduction.” In Humanities and Social Sciences in East and Central Africa: Theory and Practice, edited by Isaria N. Kimambo. Dar es Salaam: Dar es Salaam University Press.

Kimambo, Isaria N. 2008a. “Establishment of Teaching Programmes.” In In Search of Relevance: A History of the University of Dar es Salaam, edited by Isaria N. Kimambo, 107–132. Dar es Salaam: Dar es Salaam University Press.

Kimambo, Isaria N., ed. 2008b. In Search of Relevance: A History of the University of Dar es Salaam. Dar es Salaam: Dar es Salaam University Press.

Lugard, Sir Frederick. 1965. Dual Mandate in Africa. London: Routledge.

Mamdani, Mahmood. 1996a. Citizen and Subject. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; Kampala: Fountain Press.

Mamdani, Mahmood. 1996b. “Centre for African Studies: Some Preliminary Thoughts.” Social Dynamics 22 (2) (Summer): 1–14.

Mamdani, Mahmood. 1998. “Is African Studies to be Turned into a New Home for Bantu Education at UCT?” Talk at Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, University of Cape Town, 22 April, Teaching Africa: The Curriculum Debate at UCT. Centre for African Studies, University of Cape Town.

Mamdani, Mahmood. 2013. Define and Rule. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press and Makerere Institute of Social Research Press.

Nabudere, D. Wadada. 1976. Imperialism Today. Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Publishing House.

Pagden, Anthony. 1987. The Fall of Natural Man: The American Indian and the Origins of Comparative Ethnology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pagden, Anthony. 1998. Lords of the World: Ideologies of Empire in Spain, Britain and France, c. 1500–c. 1800. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Saunders, S. J. 1992. Access to and Quality in Higher Education: A Comparative Study. Rondebosch: University of Cape Town.

Tandon, Yashpal. 1979. Imperialism and the State in Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Publishing House.

Van Onselen, C. 1991. “Tertiary education in a democratic South Africa.” Unpublished mimeo.

Wolpe, Harold, and Zenariah Barends. 1993. A Perspective on Quality and Inequality on South African Tertiary Education. Belville: The Education Policy Unit (EPU), University of the Western Cape.

Speech at the 'Third World, 60 Years: The 60th Anniversary of Bandung Conference' Hangzhou Forum, on April 18–19, 2015. I would like to express my gratitude to the participants of this forum for their valuable suggestions on this article, including Shunya Yoshimi from the University of Tokyo, Stephen C. K. Chan from Hong Kong, Wang Xiaoming from Shanghai, Suren Pillay from the University of the Western Cape in South Africa, and Robert Meister from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

On 9 March 2015, Chumani Maxwele, a fourth-year political science student, emptied a container of feces over the statue of Cecil Rhodes at the University of Cape Town (UCT) campus in South Africa. Maxwele said he was protesting the “colonial dominance” still palpable at UCT. His actions marked the beginning of a series of events, including the occupation of UCT's Bremner Building by a group of students. A month later, the University Council voted to remove the statue. Chumani Maxwele told the media: “It has never been just about the statue. It is about transformation.” The petition circulated by the Rhodes Must Fall Campaign stated: “We demand that the statue of Cecil John Rhodes be removed from the campus of the University of Cape Town, as the first step towards the decolonisation of the university as a whole.”1

“Transformation” has surfaced as a rallying cry in the post-apartheid South African academy every time popular disaffection has found organized expression. North of the Limpopo, in the period that followed independence, there was another name for “transformation”; this was “decolonization”—political, economic, cultural and, indeed, epistemological. I intend to focus on the latter, knowledge production, and its institutional locus, the university.

The African university

The modern university has developed in a tension between two poles, on the one hand, a universalism based on a singular notion of the human and, on the other, nationalist responses to it. The challenge for us—which I do not take on in this essay but only refer to in the conclusion—is to rethink the relationship between the national state and the university. To do so is to arrive at our own understanding of the modern and the possibility of a time after colonialism.

What does it mean to decolonize a university, an authorized center of knowledge production? In one form or another, this question has been at the heart of discussions at African universities. I will focus on some of the discussion at some of the universities: the University of Dar es Salaam, Makerere University in Kampala, the University of Cape Town, and the Dakar-based Pan-African organization called the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA).

These discussions have developed as a series of debates on a range of issues: Africanization of staff, disciplinarity and inter-disciplinarity, the role of the intellectual and the relationship of the intellectual to society. The demand for Africanization was formulated in the older colonial-era universities soon after independence, in a debate that pits two principal ideas, justice and rights, against one another. The discussion on the disciplines and inter-disciplinarity developed in two very different contexts: as a discussion at the University of Dar es Salaam on the relevance of discipline-based education, and, at the University of Cape Town, as a set of questions about two different ways of understanding the human experience, with the disciplines studying the white experience and area studies focused on the experience of the native from the point of view of a settler observer. Connected to this were different understandings of the role of the intellectual and the relation of the intellectual to society. They raise further questions, about the relation of the particular to the universal, and the local to the global. Driving these discussions is a tension between two related but different vocations: that of the public intellectual and the scholar. The public intellectual emerged as organic to the anti-colonial movement, both integral to the nationalist movement and a beneficiary of the nationalist struggle. The scholar was the first critic of nationalism in power, drawing inspiration from a set of universal values guiding the study of an undifferentiated human. It would appear ironic that the scholar beholden to the governmental and university bureaucracy for his meteoric rise—in this case, Ali Mazrui—would appear critical of the newly independent government. To understand the changing relationship between the scholar and power, we shall examine the changing relation between the anti-colonial intellectual and nationalism, first as a popular movement and then as a form of power.

The African university and the legacy of the colonial modern

Most writings on the African university begin by acknowledging a list of premodern institutions as precursors to the modern African university. The UNESCO website references these venerable institutions from the precolonial and premodern periods. Big names abound: the Alexandra Museum and Library, Al-Azhar in Cairo, al-Zaitounia in Tunis, al-Karaouine in Fez, Sankore in Timbuktu, and so on. An ongoing debate focuses on whether or not these can be termed universities.

I begin by problematizing both the concept and the institutional history of the university, in its European and African contexts. My point is to underline the specifically modern character of the university as we know it and its genesis in post-Renaissance Europe. The European university emerged from Western Christianity, in the 12th and 13th centuries, and was institutionalized in Berlin in the 19th century, as the home of the study of this undifferentiated human.

The Latin word universitas means “corporation.” The word derives from the context in which the institution developed. The premodern university was a “corporation” of students and teachers whose position was defined by a privilege and an exemption. The Church sanctioned the “corporation” to teach, and the state gave it exemptions from financial and military services. In North and West Africa, as in the rest of the non-Western world, there was no counterpart to the Catholic Church. When those in power conferred the privilege of teaching or gifts on important scholars, the beneficiaries were individuals or families, not a corporation of teachers or students. To say this is to state the obvious: the overall context in the development of institutional learning (what we now know as the “university”) was not the same in these parts of Africa as in medieval Europe. This difference should raise a larger question: to what extent can we translate a modern category such as “university” across time?

The important point is that neither the institutional form nor the curricular content of the modern African university derived from pre-colonial institutions; their inspiration was the colonial modern. The model was a discipline-based, gated, community with a distinction between clearly defined groups (administrators, academics, and fee-paying students). Its birthplace was the University of Berlin, designed in 1810 in the aftermath of German defeat by France. Over the next century, it spread to much of Europe and from there to the rest of the world. Not only the institutional form of the university but also the intellectual traditions that have shaped modern social and human sciences are a product of the Enlightenment experience in Europe. The European experience provided the raw material from which was forged the category “human.” Although abstract, this category drew meaning from actual struggles on the ground, both within and outside Europe.

The experience from which the category human was forged was double-sided and contradictory. Internally, the notion of the human was a Renaissance response to Church orthodoxy. The human developed as an alternative to the notion of a Christian. Looking to anchor their vision in a history older than that of Christianity, the revolutionaries of France and Europe self-consciously crafted a European legacy, with its origin in classical Greece and imperial Rome. This human was more than Christian; theoretically, at least, it included those other than Christian. Externally, the notion of the human was a response to an entirely different set of circumstances—marked, not by the changing vision of a self-reflexive and revolutionizing Europe, but of a Europe reaching out and expanding in a move seeking to conquer the world—starting with the New World, then Asia and finally Africa—and then to “civilize” that world in its own image.2 Imperial Europe understood the human as a European, but colonized peoples as so many species of the sub-human.

This dual origin made for a contradictory legacy. In their universal reach, both the humanities and the social sciences proclaim the oneness of humanity and define that oneness from the vantage point of a very particular experience and its equally particular and imperious perspective. Rather than acknowledge the plurality of experience and perspective, the universalism born of the European enlightenment sought to craft a world civilization as an expression of sameness. It is the linear theory of history undergirded by this particularity of vision, and the power that drives it, that we have come to know as Eurocentrism (Amin 2010). It is this vision, and this institutional form, that was transposed to the colonies. Decolonization would have to engage with this vision of the undifferentiated human—culled from the European historical experience—which breathed curricular content into the institutional form we know as the modern university.

We can only speak of the advent of the modern university in Africa in the colonial period. Colonial universities were set up in two different phases. The first phase saw the establishment of universities at two ends of the continent. At the southern end, as with the University of Witwatersrand and the University of Cape Town, universities were an external implant. In the northern part, existing institutions such as Al-Azhar were “modernized” into discipline-based, gated communities in the image of the modern Western university (Gubara 2013).

When it came to sub-Saharan Africa, the middle bulge of the continent south of the Sahara and north of the Limpopo, the part of Africa colonized last in the late 19th century, modern universities were set up only in the 20th century. The difference between these two parts of Africa captured a difference between two historical periods: the 18th and early 19th century, when colonialism had the self-image of a “civilizing mission,” and the following century, which marked a retreat from this confident mission to a preoccupation with defending order as “customary.” Whereas universities were seen as the hallmark of the “civilizing mission” in the earlier period, they were seen as harbingers of an unruly middle class intelligentsia in the period that followed.3 This policy imperative was formulated by Sir Frederick Lugard, the scholar-administrator of British Africa. He warned of the educated native—the “Indian Disease”—and said this disease must be kept out of Africa as far as possible (Lugard 1965).

For both its institutional character and its curricular content, the colonial university drew on the modern European university, not the precolonial and the premodern tradition in Africa. The particular experience of the colonial modern shaped the internal dynamics and external perspective of the university. At the same time, universities in middle Africa were mainly a post-independence creation. They were a product of insurgent nationalism. There was one university in Nigeria at independence in 1961, 31 universities three decades later (Bako 1993). The figures for East Africa, where Makerere was the only university in the colonial period, are not that different. As the midwife of the modern university, the modern state had a limited vision: the university would produce the personnel necessary to deracialize the state and society. Limited to deracialization of personnel, both within the university and in the wider society, this vision had yet to engage either the institutional form or the curricular content that breathed life into it.

It is against this background that we can understand subsequent initiatives to reform this university.

Intellectuals, state and society in the post-independence era

Post-independence reform unfolded in two waves. The first wave was about access—Africanization—and the second about institutional reform. Given that racial exclusion was a standard feature in every colony, Africanization was a common demand throughout colonial universities in the aftermath of independence. The demand for access generated a debate between two general positions: rights and justice. The beneficiaries of racial discrimination called for equal rights for all on the morrow of independence. Its victims demanded that if discrimination was racialized, then justice too should be racialized. Whether at Makerere University in the early 1960s or at South African universities during the apartheid era, the defense of rights turned into a language for minimal reform while defending historical privilege, calling for a focus on the present and forgetting the past (moving on, let bygones be bygones). In contrast, justice provided a language for those who aimed at a thoroughgoing reform of this status quo, calling for affirmative action to redress the effects of the past. Both languages, rights and justice, were racialized in the post-colonial context. At one end of the political spectrum, the failure to think of rights outside the context of justice led to an embrace of the social inequality generated by apartheid; at its other end, the failure to think of justice outside the context of rights produced an agenda for turning the tables, in other words, revenge.

At the same time, the struggle for access had two very different histories, depending on context. Where there was no appreciable locally-settled European population and hardly any European students in local universities, as in the non-settler colonies, access was about inclusion in the teaching faculty and the top administration, and was relatively easy to achieve—and could be done without a change in the curriculum. But in settler colonies, where universities were divided into two neatly differentiated institutional categories, “white” and “black,” the integration of white universities was likely to be explosive. This is for several reasons. To begin with, the institutional separation of “white” and “black” educational institutions, whether university or pre-university, was part of a wider world of unequal access to resources, and thus unequal quality of education. This meant that when historically white universities responded to demands for social justice by admitting more “black” students through affirmative admission policies, the same universities failed—and expelled—a disproportionate number of black students as they sought to defend standards. For the black student in a historically white university, this made for an acutely alienating experience, leading the more perceptive of these students to call for a change in the content of the curriculum, one that would valorize the black (“native”) experience, and not just relegate it to the domain of area studies. This difference had further consequences: whereas the demand for access could be screened off from the demand to transform the university in non-settler contexts, this would not be so easy in settler contexts, as evidenced by the round of struggles initiated by the Rhodes Must Fall movement at the University of Cape Town. Although the demand for changing the curriculum came in non-settler contexts first—after all, political independence came to non-settler colonies in a wave of reform starting in the mid-1950s—it did not have a racial edge, as in settler contexts.

The reform movement of the 1960s unfolded in non-settler colonies. Located at two very different campuses—Makerere University, the paradigmatic colonial university, and the University of Dar es Salaam, which would soon emerge as the flag-bearer of anti-colonial nationalism—this movement was guided by two individuals championing two contrasting visions. Ali Mazrui called for a university true to its classical vision, as the home of the scholar “fascinated by ideas”; Walter Rodney saw the university as the home of the public intellectual, a committed intellectual rooted in his time and place, and deeply engaged with the wider society. From these contrasting visions would emerge two equally one-sided notions of higher education: one accenting excellence, the other relevance.

Makerere was a public university, first established in 1922 by the colonial government as a vocational college. Key administrators, appointed by the newly independent government, dictated both the direction and pace of change. The first round of change produced resounding victories for the broad nationalist camp, which called for an “Africanization” of academic and top administrative staff so the university would be national not only in name but also in composition. This change was easy to effect. With it, however, the terms of the debate changed. As the ruling party moved to consolidate its hold on power as a single party regime, the university once again turned into an oasis where the practice of academic freedom also guaranteed free political speech for those who disagreed with the ruling power. This in turn made for a growing tension between the nationalist power and the intelligentsia at the national university. A product of insurgent nationalism, the university came into collision with nationalism in power, as in most African countries.

“Africanization” made for a meteoric rise in the career of young scholars. The best known of these was Ali Mazrui. Freshly returned from Oxford with a DPhil, Ali was promoted to become Makerere's youngest professor and the head of its Department of Political Science and Public Administration. The turning point at Makerere was the birth of the magazine Transition (1961–1968). Edited by Rajat Neogy, and joined by an array of scholars and public intellectuals, Transition was a blend of two different kinds of media, a journal and a magazine, and provided space for university-based intellectuals to write for a public that included both the gown and the town. Designed to be a literary organ for East Africa's writers and intellectuals, Transition became what many considered Africa's leading intellectual magazine. Those who wrote for Transition ranged from leading novelists (Nadine Gordimer, Chinua Achebe, James Baldwin, Paul Theroux) to state leaders (Julius Nyerere).4